Inspired by nature

Researchers are applying lessons learned from butterflies, beetles, mussels, and other creatures to problems of human survival.

By Emily Sohn

People do a lot of things that plants and animals can’t do. We can talk and read. We can play computer games and go snowboarding—stuff that no worm or fern could ever do.

But nature is no slouch. There are lots of things that people wish they could do, and, in many cases, nature has already come up with a solution.

Some insects walk on water. Geckos can crawl across ceilings. Leaves turn sunlight into stored energy. Burrs stick to your socks like Velcro. Certain birds sail on the wind for days without making any effort at all.

|

|

A water strider can walk on water.

|

| U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service |

Often, millions of years of evolution have created the most efficient and environmentally friendly ways to do things, says author and environmentalist Janine Benyus.

Simple creatures, she says, “may harbor techniques that are in fact far more advanced than ours, and we can learn a lot from them.”

Increasingly, scientists are catching on. Around the world, researchers are looking to nature for solutions to all sorts of problems. Inspired by nature, they’re concocting stickier glues, stronger materials, zippier propellers, and much more.

The science of copying nature has come to be known as biomimicry, a word popularized by Benyus in a 1997 book with the same name.

The key is to ask yourself some basic questions about the world around you, Benyus says. What would nature do? And if it hasn’t been done, why not?

Sturdy shells

What makes a material tough?

The giant pink queen conch, for instance, has a beautiful shell that’s extremely strong and hard to break. This mollusk’s shell is made almost entirely of a chalky mineral known as aragonite—a form of calcium carbonate. Yet the conch shell is hundreds of times stronger than the mineral by itself.

|

|

A giant pink queen conch.

|

| Case Western Reserve University Photography Laboratory |

It turns out that the shell owes it strength to a secret ingredient—molecules known as proteins. These proteins form a kind of web that surrounds the mineral crystals and holds them together.

When you bang on a conch shell, it doesn’t split. Instead, the shell develops tiny cracks that spread the impact throughout the material. This keeps the shell from breaking.

The scientists at Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland who made this discovery a few years ago and other researchers hope to use this information in their laboratories to make lightweight materials that are just as difficult to smash.

Snagging carbon

When you breathe, you inhale oxygen and exhale carbon dioxide. A molecule of carbon dioxide is made up of one atom of carbon and two atoms of oxygen.

Plants have an amazing ability to remove carbon dioxide molecules from air, extract carbon atoms, and use them to make useful compounds, such as sugars.

At Cornell University, chemist Geoffrey Coates wants to make plastics the way nature’s plants make sugars. His goal is to find materials that extract carbon directly from carbon dioxide as efficiently as plants do.

|

|

Green plants turn sunlight into stored energy and use carbon dioxide from the air to make cellulose and other carbon-containing compounds.

|

| Susan Boyer, Agricultural Research Service, U.S. Department of Agriculture |

In another project inspired by nature, Coates recently discovered a way to make certain useful plastics from molecules found in many types of bacteria. Such plastics have the advantage of being biodegradable.

Sticky stuff

Sometimes, it’s useful to have materials stick together. That’s where gecko tape might come in handy.

Just last year, scientists from Lewis & Clark College in Portland, Ore., discovered how the hairs on a gecko’s feet allow it to stick firmly to ceilings and even walk around on them (see http://www.sciencenewsforkids.org/articles/20031119/Feature1.asp ).

Such information could lead to manufactured gecko tape. Imagine robots that can climb walls, ouch-less Band-Aids, furniture padding that can easily be changed, and maybe even Spider-Man gloves.

Then there’s color.

Blue jeans. Green hair. Purple plates. People often use dyes or pigments to color foods, fabrics, and lots of other materials. But many of these coloring agents are toxic. Using them can be messy and dangerous.

Nature has another answer. The brilliant blue of certain butterfly wings, for example, doesn’t come from chemical pigments. Instead, the color comes from the way light is reflected by scales that cover the butterfly’s wings. Such reflections also produce the iridescent colors of a peacock’s feathers or the bright blue of a bluebird’s plumage.

|

|

Eastern bluebird.

|

| Dave Menke, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service |

Some companies have started to use a similar strategy, creating patterns on surfaces to reflect certain colors of light, to make brilliantly colored objects or even new types of computer displays.

Helping builders

Biomimicry can help architects and builders design homes and other structures that improve people’s lives, Benyus says.

To put up a sturdy building, for example, a construction company could pound steel columns deep into the ground to create a firm foundation. Or, a builder could try to copy the root systems of ancient trees that have kept enormous trunks upright for thousands of years.

Here’s another example. Some desert-dwelling beetles have bumps on their stiff outer wings. The top of each bump is smooth, like glass, and attracts water. The troughs in between the bumps are covered with wax. Wax repels water.

On foggy mornings, tiny water droplets collect on the wings. The captured water droplets coalesce and grow, then roll off the backs of the beetles into their mouths.

Now, British engineers are making sheets and tiles with beetle-like bumps. Such a surface is covered with large numbers of tiny glass spheres, each about the size of a poppy seed, embedded in a thin layer of wax. Tents covered with this material could provide water for refugee camps and poor agricultural communities in drought-ridden nations.

Simple mollusks, such as mussels, can provide solutions for tricky household and even industrial problems.

|

|

Simple mollusks, like this freshwater mussel, can provide solutions for tricky industrial problems.

|

| Eric Engbretson, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service |

Benyus once went to the Galapagos Islands in the Pacific Ocean with a group of wastewater treatment engineers. One problem the group faced was stopping the mineral buildup and scaling that often clogs or ruins pipes.

For an answer, they looked to the way mollusks make shells. The shells of these animals are basically built out of the same minerals that can clog pipes—calcium carbonate. Because the shells grow to a certain size and no larger, these animals have a way to stop the buildup of minerals. They release a special protein to do so.

One company has used these proteins as a model to create a line of products for preventing corrosion. The company describes their corrosion-preventing proteins as “non-hazardous, nontoxic, hypoallergenic, environmentally friendly, and biodegradable.”

Other companies are looking to plants that naturally resist toxic mold and repel dangerous microbes to inspire coatings for walls in houses. The lotus plant is famous for making water bead up and roll right off (see http://www.sciencenewsforkids.org/articles/20030305/Note2.asp ). Now, it’s possible to build lotus-like walls that don’t need to be scrubbed. Rainwater by itself cleans them off.

Nature by design

The ultimate goal, Benyus says, is to mimic not just materials but entire processes in nature.

|

|

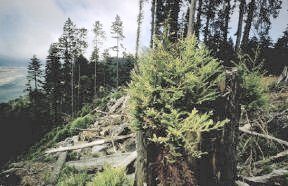

Among the world’s tallest trees, redwoods have amazing root systems that help keep them upright. These trees can also often survive forest fires.

|

| National Park Service |

For example, instead of cutting down trees and collecting materials to put up buildings, someday we may be able to do what nature does: Build structures from the bottom up.

Abalones, for instance, excrete a liquid that they use to make very tough shells. Wouldn’t it be great if builders could do that, too? “Imagine pouring a liquid into a mold to assemble structures,” Benyus says.

At a conference last spring in Minneapolis, Benyus encouraged architects and builders to make homes and other structures as beautiful as butterflies, as waterproof as beetle shells, as resistant to fire as redwood trees.

Nature provides the lessons. “There are amazing things right outside your door,” she says. There’s something new to learn from every living thing.

Going Deeper: