Fishing for Giant Squid

An underwater camera has snapped the first pictures of a live giant squid.

By Emily Sohn

Stories of giant sea monsters have terrified people since ancient times. Some of the scariest tales involve a gargantuan squid that attacks boats and snares sailors with its gnarly tentacles.

Over the years, the long-armed creatures have gained mythical status. Authors have written about them. Artists have painted them.

|

|

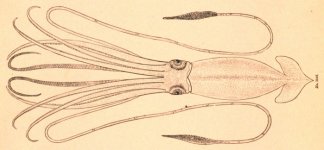

This drawing of a giant squid was based on a specimen found on the coast of Newfoundland in 1874. |

| NOAA Photo Library |

As myths go, however, giant squid are unusual because they actually exist. Sixty-foot-long specimens have washed up on beaches around the world. But the animals have always been dead by the time they appeared on shore.

Determined to find giant squid alive and in their home waters, a small but dedicated group of scientists has been aggressively scouring the deep sea for many years.

“For reasons we’re not quite sure of, we haven’t been able to find this guy alive,” says Lou Zeidberg, a marine biologist at the Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute in Moss Landing, Calif.

Until now. A group of Japanese scientists recently caught one of the elusive creatures on film. With an underwater camera, the team followed a 26-foot-long giant squid at a depth of 3,000 feet near Japan’s Ogasawara Islands.

|

|

A giant squid goes for a baited fishing line. |

| Courtesy of Tsunemi Kubodera and Kyoichi Mori |

The photos—about 550 in all—show the giant squid lunging for bait, getting stuck, and losing one of its tentacles.

Skin displays

Giant squid, known to scientists as Architeuthis, is just one of some 700 species of squid, which belong to a larger group of animals called cephalopods. The group also includes octopuses, cuttlefish, and the nautilus.

Cephalopods are a compelling collection of creatures to study, Zeidberg says, because there’s a lot to learn about them. For one thing, they have special cells in their skin that can change color almost instantly to create elaborate patterns and displays.

|

|

A small squid known as Illex illecebrosus cruises over a sandy area of the seabed. |

| William Millhouser, NOS/NOAA Photo Library |

“People spend a lot of money creating light shows to come close to what cephalopods can do naturally,” Zeidberg says.

Cephalopods also have highly developed eyes, similar to ours. They have long tentacles extending from their bodies. And they’re one of the few animals in the world that use jet propulsion to move. They squirt water out of their bodies in one direction in order to move in the opposite direction.

“When you see them dead in a fish market, they’re kind of disgusting,” Zeidberg says. “When you see them alive, they’re just amazing. I could stare at them forever.”

Diversity

Among squid, Architeuthis gets most of the public’s attention thanks to its size. Scientists, however, are probing the startling diversity within the squid world. There are squid so small that babies are the size of a grain of rice, and adults grow to be just 6 inches long. Jumbo squid are about 6 to 10 feet long. Giant squid can reach 60 feet. Other species fit somewhere in between.

Zeidberg and his coworkers have been catching squid to study in the lab. They want to know how much fish squid eat, how fast they swim, how much oxygen they use, how their color-changing cells work, and why their ranges have been spreading in some places but shrinking in others.

This year, for example, was a bad one for squid in California, Zeidberg says. That’s a problem because fisheries in California usually catch more squid than anything else, he says. Most of the catch gets sold to China and Japan. The rest is eaten here as calamari.

|

|

Squid for sale in a Japanese market. |

| Dr. Roger Mann, VIMS/NOAA Photo Library |

Squid fishing is a multimillion-dollar industry. So, learning more about the animals might help scientists regulate squid numbers and prevent expensive losses.

Light attraction

Most types of squid are easy to spot in the wild because they regularly come to the surface, and they’re attracted to the lights on cameras that researchers use. “Jumbo squid just love us,” Zeidberg says. “They use our lights to hunt other animals.”

Giant squid are much harder to see. For one thing, they live at extreme depths, where the environment is cold and harsh. The only practical way for people to get a glimpse of what’s down there directly is with remotely operated vehicles (see “Explorer of the Extreme Deep“).

Such vehicles, however, are not ideal for squid hunting. They’re expensive to operate. They’re noisy. Their lights are blindingly bright. And they move at only a few miles per hour, Zeidberg says. Giant squid, on the other hand, can probably swim up to 15 miles per hour.

“Architeuthis lives its whole life in the deep sea,” he says. “When it sees something bright and doesn’t know what it is, it probably doesn’t want to find out.”

Knowing that sperm whales feed on giant squid, Japanese researchers started setting out cameras where whales gather near islands south of Japan. The scientists dangled the cameras above hooks baited with small squid and mashed shrimp.

On Sept. 30, 2004, one of these cameras recorded the pale form of a giant squid as it attacked the bait. Giant squid have eight arms plus two extralong tentacles. The photographed creature wrapped the ends of its paired tentacles around the bait, and one tentacle snagged on the hook. The camera caught images of the squid fighting to free itself.

|

|

The photographed giant squid lost part of one of its tentacles before it escaped. This tentacle section was then hauled to the surface. |

| Courtesy of Tsunemi Kubodera and Kyoichi Mori |

After more than 4 hours, part of the tentacle tore off, and the squid vanished. When the tentacle section was hauled to the surface, its suckers could still grab the boat and even people’s fingers.

Inspiring images

By bringing attention to squid, the images of a live giant squid may inspire people to care more about the animals, their relatives, and the oceans they live in, Zeidberg says.

At the same time, actually finding something that has been sought for so long may have a downside, too. “When a mystery finally gets solved, there’s one less thing to wonder about,” Zeidberg says.

Perhaps that’s what author John Steinbeck meant in his 1941 book The Log from the Sea of Cortez. “Men really need sea monsters in their personal oceans,” Steinbeck wrote. “An ocean without its unnamed monsters would be like a completely dreamless sleep.”

Going Deeper: