Coral gardens

An expedition to an undersea mountain reveals large corals, brilliant sponges, and other strange sea creatures.

By Emily Sohn

On their first visit to Davidson Seamount in 2002, scientists realized that they had discovered a very unusual place. What was once an underwater volcano has become home to an unexpectedly diverse community of enormous and colorful sea creatures.

In this beautiful environment, bright-pink corals tower more than 10 feet tall. Delicate, lacy sponges mingle with brilliant, lemon-yellow sponges the size of boulders. There are shrimp, crabs, sea anemones that look like Venus flytraps, as well as red octopuses, sea stars, fish, and more. All these creatures live between 4,000 and 12,000 feet beneath the surface of the Pacific Ocean.

|

|

A Venus flytrap sea anemone on Davidson Seamount.

|

| © 2002 MBARI/NOAA |

“It’s an Alice in Wonderland place,” says Dave Clague, a geologist at the Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute (MBARI). “I’ve done a lot of dives in the ocean, and I’ve never seen biological communities like this before in the deep sea.”

In January 2006, researchers returned to Davidson Seamount, bringing equipment that enabled them to better explore this intriguing underwater ecosystem. This time, they focused on the area’s large gardens of coral. It’s rare for corals to be so big, bright, and diverse in the cold, dark depths, and the scientists wanted to learn more.

The team included scientists from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s (NOAA) Monterey Bay National Marine Sanctuary, MBARI, and Moss Landing Marine Laboratories. A film crew from the British Broadcasting Company (BBC) tagged along, and the team posted dispatches, videos, and photos online during the 10-day expedition (see oceanexplorer.noaa.gov/explorations/06davidson/welcome.html).

Undersea mountain

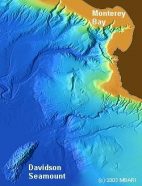

Located 75 miles southwest of Monterey, Calif., Davidson Seamount is one peak in a long chain of underwater mountains that stretch offshore from Baja, Mexico, to central California, Clague says.

|

|

Davidson Seamount is an extinct volcano located about 75 miles (120 kilometers) southwest of Monterey Bay, California.

|

| © 2003 MBARI |

The seamount used to be an underwater volcano, but it stopped erupting some 10 million years ago, according to analyses of rocks collected on the first expedition. Today, the seamount is 26 miles long and 7,900 feet high, about as lofty as Mount St. Helens in Washington State.

Scientists made maps of the seamount in the 1930s. But because the area is so deep, exploring it was impossible before the invention of robotic machines called remotely operated vehicles (ROVs). Pilots control ROVs from the sea surface, and the machines carry cameras, mechanical arms, and other equipment.

For the 2006 expedition, the ROV Tiburon joined the team. A group of otters greeted the research ship Western Flyer as it left the bay, and a pack of dolphins and porpoises escorted it along its 6-hour journey.

For the next 10 days, Tiburon explored underwater slopes for 8 to 10 hours a day, says team member Allen Andrews, a marine biologist at Moss Landing Marine Laboratories.

|

|

This photo shows three types of sponges growing on the lava of Davidson Seamount: large yellow sponges; white, frilly sponges (left); and white, bushy sponges. The large yellow sponge provides a perch for several basket stars and pink shrimp.

|

| © 2006 MBARI/NOAA |

The ROV used its arm to collect samples of rocks, mud, corals, and other animals. It also carried a high-definition video camera that sent images to the surface. Scientists on the ship took turns sitting in the “science chair,” where they watched the spectacular view on a big screen. They saved the recordings of the scenes for later analyses.

“It’s very exciting to get to the bottom and see things that no one has ever seen before,” Andrews says.

Valuable real estate

Seamounts are valuable real estate for deep-sea creatures because they provide rocky surfaces to which the animals can affix themselves. Scientists suspect that currents play an important role, too, by delivering streams of nutrients to fuel the ecosystem.

|

|

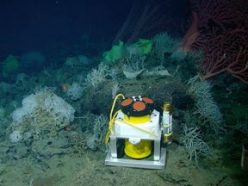

Equipment placed on the seafloor measures currents flowing over the top of Davidson Seamount.

|

| © 2006 MBARI/NOAA |

On the most recent expedition, researchers brought along equipment to measure currents so that they could get a sense of how the seamount’s ridges have become so rich with life.

Mapping the patterns of currents could also help explain why certain types of corals live where they do. For example, on the 2002 expedition, scientists noticed that two types of coral dominated the mountaintop, Clague says.

Most areas were crowded with big pink bubblegum corals, but another section of rock was covered with tiny, thumb-size corals and crusty sponges. As different as the two communities are, one might be overtaking the other, the researchers suggest.

|

|

These bubblegum corals grow to more than 8 feet tall on Davidson Seamount. They eat tiny particles that they’ve filtered out of the passing currents. Unlike tropical corals, deep-water corals live in water that is just a few degrees above freezing.

|

| © 2006 MBARI/NOAA |

Another goal of the mission was to figure out how long the seamount’s big corals live. Evidence from previous expeditions suggests that some corals might be more than 100 years old. Andrews plans to test the new samples for a type of radioactivity that indicates age.

“There are a lot of neat questions that have never been asked,” Clague says. “We have never seen something so dramatic in the deep sea.”

Unexplored realms

Like the majority of the world’s oceans, much of the Davidson Seamount remains unexplored. Learning more about these special places will be an essential part of keeping them in good shape, Andrews says.

|

|

Bamboo corals on Davidson Seamount may live to be more than 200 years old.

|

| © 2006 MBARI/NOAA |

That’s important because deep-sea coral communities appear to be very old and very fragile. It would take them a long time to recover from damage, if they recovered at all.

“There are seamounts around the world that used to have very diverse coral communities, and they are completely gone,” Andrews says. “If we don’t protect this place from being damaged by human activities, we will lose something that no one will ever be able to see again.”

Going Deeper: