A satellite of your own

Some kids are getting a chance to design, build, and launch an Earth-orbiting satellite.

By Emily Sohn

A rocket soars into space. It releases a satellite, which goes into orbit around Earth. The satellite begins collecting data and sending signals. You listen in on the information coming from outer space, proud that you played a role in designing and constructing the satellite.

Just a dream?

|

|

Launched in 1999, NASA’s Terra satellite orbits Earth, collecting environmental data. Building and operating the satellite has cost more than 1 billion dollars.

|

| NASA |

Building a traditional Earth-orbiting satellite normally takes years. Construction costs can be as high as $250 million, or more. Most members of the design teams have worked in the field for a long time. They hold advanced degrees in math, science, or engineering.

But things are changing. High costs, stiff educational requirements, and long start-up times are no longer an obstacle to space exploration, says Bob Twiggs, who’s an engineer at Stanford University. Twiggs and his coworkers have developed a new generation of small, inexpensive Earth-orbiting satellites that go from concept to launch in a year.

The whole point of these low-cost satellites, Twiggs says, is to teach students as much as possible about how satellites work.

|

|

Bob Twiggs of Stanford University holds an inexpensive, cube-shaped satellite, or CubeSat.

|

| Courtesy of Ben Yuan |

So far, college students have built and launched about a dozen of these cube-shaped satellites, or CubeSats, Twiggs says. At least 15 more are ready to go. Those already in orbit take pictures, collect data, and transmit information back to Earth, just as regular satellites do.

Satellites for kids

But you might not even have to wait until you get to college to start designing and building your own satellite. A new program called KatySat (which stands for “Kids Aren’t Too Young for Satellites”) aims to get teenagers involved, too.

“My goal is to increase the relevance of space to more people,” says Ben Yuan, an engineer at Lockheed Martin in Menlo Park, Calif. He came up with the idea for KatySat, which brings the CubeSat program to high schools.

|

The KatySat approach “simplifies space technology to its most basic components,” he says. “We aren’t worried about how powerful or cutting-edge [the technology] is. We’re worried about making it accessible and simple enough.”

Once kids understand what satellites can do, Yuan adds, the kinds of applications they’ll come up with may be unlimited.

“We’d like to put this technology in your hands,” he tells kids. “We’re going to teach you how to operate a satellite. Then, we want to turn it over to you as a sandbox for you to play in. We want you to take the technology into new directions that we haven’t thought of yet.”

A compact package

A standard CubeSat is 10 centimeters (4 inches) long on each side and weighs about 1 kilogram (2.2 pounds). It takes about $40,000 to build a CubeSat and the same amount to launch it.

Depending on the type of equipment inside, a CubeSat can take pictures, collect data for experiments, and do other scientific tasks. The first KatySat, which Yuan is working on with students at Independence High School in San Jose, Calif., will have two radios. One radio will transmit high-quality photos to students on the ground. The other radio will be for communication.

|

|

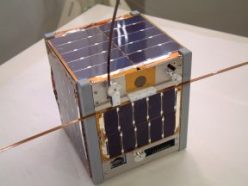

A standard CubeSat is about 10 centimeters long on each side and weighs about 1 kilogram. This one, developed by students at the University of Tokyo, was the first CubeSat to be launched into orbit.

|

| Courtesy of Ben Yuan |

Yuan envisions students at different schools talking to each other by satellite. He also wants students to use KatySat to choreograph multimedia presentations on the computers of their peers around the world.

Education isn’t the only goal of CubeSats, Twiggs says. Because these tiny, technology-filled boxes are relatively inexpensive to build and can be put together quickly, they’re perfect for testing new technologies that might one day be used on major space missions.

The biggest challenge now facing researchers is to find ways to bring the satellites back to Earth after a year or two. Otherwise, major highways of space junk could accumulate as CubeSats become more common and students move on to other projects.

In the meantime, college and high school students are getting a chance to learn what it takes to venture into space.

Someday—perhaps a lot sooner than you’d imagined—you might get to design, build, and launch your own satellite. If you do, you’re bound to have fun. And you might also get hooked on science for life.

Going Deeper: