Saving Africa’s Wild Dogs

Learning more about African painted dogs may help keep these wild animals from dying out.

By Emily Sohn

For Gregory Rasmussen, a typical workday starts just before sunrise. The wildlife conservation biologist studies African painted dogs in Zimbabwe, and that’s when these endangered animals usually wake up.

|

|

Two African painted dogs drinking at a pool. |

| © Painted Dog Project Zimbabwe |

As a pack of wild dogs sets off to hunt for antelope and other prey around 5 a.m., Rasmussen follows in a Land Rover. Using a small computer, he records where the dogs go and what they do.

Between about 10 a.m. and 4 p.m., the dogs rest, and so does Rasmussen. Then, the dogs go hunting again, and the biologist tags along. When the moon is full, the dogs like to hunt in the middle of the night, so Rasmussen sometimes gets little sleep.

The biologist doesn’t set up a tent because he has to be ready to take off at a moment’s notice. So, he simply rolls out a mat on which he can snooze. He never knows when or where his workday will end. The painted dogs typically travel 30 miles a day, and they never sleep in the same place twice.

Rasmussen spends up to 28 days at a time tracking and watching the brown, black, and tan-splotched dogs, which have big ears. No two look alike.

|

|

African painted dogs have large ears, as seen in this puppy. |

| © Painted Dog Project Zimbabwe |

“It’s heaven, absolute heaven,” he says. “It’s amazing following them.”

Rasmussen’s goal is to learn everything that he can about painted dogs. He has also developed camps for kids and educational programs for adults to get local people involved in saving the animals from extinction. This effort may be exactly what the dogs need.

Bad reputation

A century ago, as many as 500,000 painted dogs lived throughout Africa. Today, scientists know of about 2,500 dogs that live in just four countries: South Africa, Tanzania, Botswana, and Zimbabwe. Perhaps 2,000 more are scattered across other parts of Africa.

In recent times, thousands of dogs have been caught in traps or hit by cars. Prejudice is a major factor in their disappearance, too, Rasmussen says. Many people believe the dogs attack farm animals. Other people simply dislike them for no good reason.

|

|

Young African painted dogs. |

| © Painted Dog Project Zimbabwe |

“A farmer’s wife came up to me in Zimbabwe and said, ‘Why do you study such horrible animals?'” Rasmussen says. “She was maybe 40 years old. By the time she was growing up, the dogs were already extinct in her area.”

To find out whether the dogs deserved such a bad reputation among farmers, Rasmussen followed the animals to see what they eat. He studied their excrement for evidence of livestock hair. He found no signs that painted dogs are a threat to livestock.

“We exploded a number of myths,” he says. “Farmers like to say [the dogs] are killing all their cows, but this was not true in any one of my studies.”

Admirable dogs

People have no reason to fear the painted dogs. In fact, research shows that there is a lot to admire about them.

Most animals, including primates, live in ranked groups. Individuals at the top of the hierarchy are bossy, and they get the most food.

|

|

A pack of African painted hunting dogs on the road. |

| © Painted Dog Project Zimbabwe |

Painted dogs, on the other hand, depend on one another. Even though they live in packs led by one male and one female, each animal has an important role. The strong take care of the old and the sick. And they share food equally.

“The whole system runs on cooperation,” Rasmussen says. “They never fight. There are very few species that don’t fight.”

Even dogs that would get teased if they were people get respect from their canine peers. Rasmussen remembers one male dog that always seemed to get lost. Nicknamed Magellan, the animal was a goofball. But when the pack had puppies, the other adults recruited him to babysit.

The dogs have many good qualities, Rasmussen says. “It’s easy for us to explain why we want to look after them.”

Pack survival

One of Rasmussen’s most important findings is that there is a “magic number” of individuals in a pack. In order for puppies to have a good chance of surviving, there must be at least five or six adults in a group. If a pack is smaller than that, losing one dog is like losing the thumb from your hand. Functioning becomes difficult.

|

|

Greg Rasmussen fits an African painted dog with a radio collar and takes a blood sample to check for disease. |

|

© Painted Dog Project Zimbabwe |

For this reason, Rasmussen and his coworkers focus their work on protecting the packs. Sometimes, he and his coworkers rescue injured dogs and nurse them back to health before returning them to their homes.

The researchers also put radio collars on many dogs, especially ones that live outside of national parks. The receivers show the scientists where the animals are.

Dog pictures

Painted dogs can be hard to spot in the wild. Alison Nicholls, an artist based in New York, is one of the lucky ones. After seeing the striking creatures in Africa, she started painting them. Now, she uses her art to aid conservation.

|

|

Artist Alison Nicholls sketches in the Makgadikgadi Salt Pans of Botswana. |

| Courtesy of Alison Nicholls |

“A lot of people who have been to my exhibitions say, ‘Oh, I love that painting,'” she says. “Then, they want to know more about the species and the country.”

When she sells dog paintings, Nicholls gives most of the profits to Rasmussen’s Painted Dog Conservation Project. Next year, she hopes to get funding from the Worldwide Nature Artists Group to return to Zimbabwe to paint more dogs.

|

|

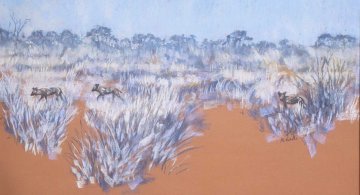

Titled “On the Trail,” this pastel painting by wildlife artist Alison Nicholls shows three painted dogs in Africa’s Kalahari Desert. |

| Courtesy of Alison Nicholls |

With both art and science on their side, these animals may yet have a future in Africa.

Going Deeper: