Concerns about Earth’s fever

The burning of fossil fuels is causing our planet to heat up — with consequences for all living things

With drought causing dry conditions in California, the state has suffered many wildfires. This one raged in July 2015 in Hayfork. A November 2015 report concluded climate change has definitely worsened recent wildfires in this state.

Beyond the Trail/Flickr (CC-BY-NC 2.0)

During the first two weeks of December, the United Nations is holding a major meeting in Paris, France. Delegates from 196 nations will be trying to put together a treaty — a set of binding laws — aimed at slowing the rise in Earth’s surface temperatures. Here is a rundown of the issues that will be driving those negotiations.

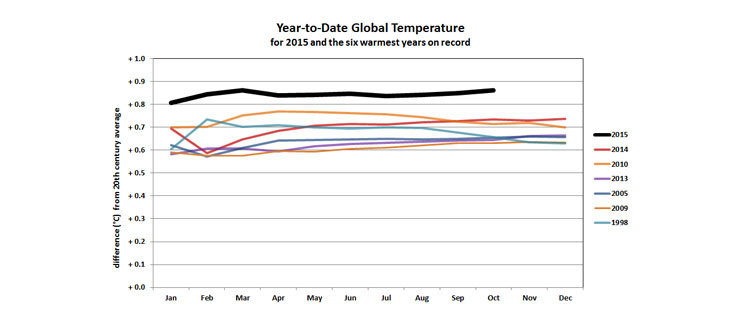

If you are 10 years old, you have lived through at least five of the six years that have been hottest across the globe since record-keeping began. And that was back in 1880. These extra-warm years are — in decreasing order of heat — 2014, 2010, 2013, 2005, 2009. And 2015? It’s on track to be hotter still, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, also known as NOAA.

Consider just this past October. It’s the most recent month for which data are available. On November 19, NOAA reported that the previous month’s average temperature across Earth’s land and oceans was the highest for any October in 135.8 years. That’s when global recordkeeping began. Overall, October’s temperatures were 0.98° Celsius (1.76° Fahrenheit) higher than the 20th century average of 14 °C (57.1 °F). October 2015 also marked the sixth month in a row that the global temperature hit a new record high.

Temperatures vary from place to place. Still, across the planet there has been a trend of steadily increasing warmth.

Global temperatures naturally bounce around from day to day, season to season and year to year. But average temperatures have risen exceptionally fast since the late 1800s. One big reason: Humans have been spewing pollutants into the air that hold in the sun’s warming rays. Such greenhouse gases are released every time someone burns fossil fuels (such as coal, oil or gas) to drive a car, to heat or cool a building or to run some factory. Chief among them is carbon dioxide.

Recent data have shown that levels of carbon dioxide in Earth’s atmosphere are now rising at rates higher than at any time since dinosaurs walked the Earth.

“So many things in our lives are influenced by climate,” notes Jessica Hellmann. She works at the University of Minnesota in Minneapolis. There, she studies the impact of climate change on animals, including us. “Some parts of the world will experience more climate change than other parts, but nowhere will escape its effects completely,” she observes.

Climate change and global warming are sometimes thought of as things that will happen in the future. But scientists are finding increasing evidence that the planet is changing now — and that people must take a large share of the blame.

But if people are responsible, they also can become part of the solution. And that’s the idea behind the December meeting in Paris. Organized by the United Nations Environment Program, it will bring delegates together to talk about what they can do to help slow Earth’s slowly building fever.

(Story continues below image)

It’s getting hot in here

Last year, the average temperature across all land and ocean surfaces was 0.69 °C (1.24 °F) above the 20th century average. This temperature surpassed the second hottest years (2010 and 2005) by 0.04 °C. Yet although 2014 was looking like the hottest recent year — until 2015 showed it up — both 2010 and 2005 were very close behind.

In the end, what really matters is the trend that shows Earth is steadily warming, says Allegra LeGrande. This climate scientist works at the NASA Goddard Institute for Space Studies and the Center for Climate Systems Research, both in New York City.

It may not seem like warming by less than 1 °C should cause much of a problem. But it does. First, the warming isn’t equal everywhere. Some places, especially the Arctic, are warming far more quickly than elsewhere. And even small temperature increases can cause big changes in places where the weather is near the temperature at which water freezes.

For instance, parts of the Arctic ground remain frozen year-round. This permafrost area not only locks up lots of carbon, but also lots of methane. Both, if they got loose, could pump up levels of greenhouse gases in the air. And that could warm the atmosphere even more if the permafrost thawed. And it is thawing.

That permafrost has been collecting carbon for more than 35,000 years. And it’s a lot of carbon, almost twice as much as the atmosphere already holds, reports Travis Drake of the U.S. Geological Survey in Boulder, Colo. and his colleagues. As this soil warms, microbes now can chow down on organic acids in it. This quickly frees up much of that carbon, a new study by Drake’s team found — creating carbon dioxide.

Thawing permafrost could cause far more warming than fossil-fuel use does now. In their new 8-day study, they showed that thawing permafrost lost half of the dissolved organic carbon it had been storing. Drake’s team shared its findings on October 27 in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

A tiny warming at those sites also can further promote the melting of glaciers and ice sheets. The resulting water that flows into the ocean causes sea levels to rise.

Global warming heats the oceans. And its cold water will expand as it warms up. Scientists call this thermal expansion. That adds to rising sea levels. Over the past two decades, sea levels have risen, on average, about 3 millimeters (0.12 inch) per year.

That double-whammy may explain why Hurricane Sandy was so destructive when it hit the eastern United States in October 2012. Powerful waves and flooding caused more than $79 billion worth of damage to buildings, roads, electrical systems and other services. Some 147 people died in the storm, according to the National Hurricane Center Tropical Cyclone Report.

Rising temperatures also can damage plant growth by stressing the greenery. Senthold Asseng is an agricultural engineer who works at the University of Florida in Gainesville, Florida. He was curious about how that stress might affect crops that serve as foods. Wheat, for instance, “represents 20 percent of calories consumed worldwide,” he notes.

Asseng led a group of 50 scientists from 15 countries who created a computer model to improve predictions about how heat affects wheat. For every 1 degree Celsius increase in the average global temperature, they concluded the world stands to lose 6 percent of its wheat crop. This means that even less of this grain will be available to feed the planet’s expanding human population. Asseng and his team reported their findings in December 2014 in the journal Nature Climate Change.

Weird weather

But climate change is not just about rising temperatures. The sun’s rays drive the world’s weather. So hotter temperatures also affect patterns of winds, precipitation and cloud cover.

“When you warm the climate, we think wet areas will get wetter and dry areas will get drier,” says Gabriel Vecchi. He is a scientist who uses math to understand how climate change affects the way the atmosphere and oceans move. Vecchi works for NOAA in Princeton, N.J.

Earth’s normal wind patterns move moisture in the atmosphere from dry areas to wet areas, he says. When temperatures rise, the atmosphere pulls more water from the land. So even if there are just a few drops, as in dry areas, the warm air pulls them up. Because warm air holds more water than cool air, winds can move water from dry regions to wet ones.

The result: Dry areas will suffer more droughts and wetter areas will experience more flooding. Also, says Vecchi, rainstorms can release more rain, further increasing the risk of floods.

It’s difficult to say that any single weather event is caused by climate change. But scientists have found that climate change can intensify extreme events. One extreme event occurred in the United Kingdom during the winter of 2013-2014. Big storms brought torrents of rain. This caused huge floods that destroyed homes and businesses. People also suffered cuts in their access to electricity and major disruptions to travel.

Climate change didn’t cause these floods. It may have made them worse, but tying particular extreme weather events to climate change remains very challenging, notes Stephanie Herring. She’s works at NOAA’s National Centers for Environmental Information in Boulder, Colo. She was the lead editor of a massive international report on weather extremes in 2014. It was issued by the Bulletin of the American Meteorological Association, or BAMS. This report did not tie the U.K. flooding to climate change.

But at a webcast news briefing on November 5, she noted that not showing a link between a particular event and climate change does not mean one did not exist. It merely means, she says, that based on the studies that scientists conducted, one did not clearly emerge. She said science cannot rule out that “there were other factors that were not investigated that may have been influenced by climate change.”

And sometimes, wildfires are not the worst consequence of warming temperatures. India, for instance, experienced its second deadliest heatwave on record in May 2015. It killed 2,500 people.

Killer bites

A warming climate also increases the area where certain infectious diseases might occur. Scientists are particularly concerned about diseases carried by insects and other animals that serve as vectors.

When a mosquito or tick bites an infected animal and then bites a person, it passes along the disease. Examples of such vector-borne diseases include dengue fever, malaria, West Nile disease and Lyme disease. Some of these can be deadly.

Cold snaps can kill the insects that carry such tropical diseases. That has kept these infections from becoming a problem in places such as northern Europe, the United States and Canada. But with global warming, the period of time when insects in those regions can reproduce is increasing, says Jolyon Medlock.

Medlock is a medical entomologist. That is a scientist who studies insects that transmit disease. He works for Public Health England in Porton Down. In March 2015, he and his colleagues published a review in the journal The Lancet. It predicted climate change will make the diseases that are spread by mosquitoes more common in parts of Europe. “As soon as it warms, the whole insect life cycle accelerates,” Medlock explains. “They digest blood quicker, lay more eggs, and they reproduce quicker.”

The new mosquitoes probably arrived in tires imported from warm countries in Asia. When Europe’s climate was cooler, that wasn’t a problem. The mosquitoes didn’t have enough time to reproduce in large numbers before being killed off by the cold. But that’s no longer assured.

Similarly, malaria has re-emerged in Greece. And West Nile virus can now be found throughout parts of Eastern Europe, the researchers note.

The researchers also looked at how the disease called chikungunya might spread across England. That disease is not normally deadly. But it causes short-term fever and severe joint pain that can last months. The analysis suggested that if the new mosquitoes become established, by 2041, London could see a whole month each year during which it would be possible to catch chikungunya. And within another six decades, it found, mosquitoes might be able to spread the disease in southeast England for up to three months each year. That could expose millions of people to the disease.

Living with climate change

Vector-borne diseases, crop failure, coastal erosion and heat stress are all serious threats related to climate change and global warming. “There are things people and governments can do to make themselves better able to tackle climate change,” says Minnesota’s Hellmann. People have the power to mitigate and adapt to those threats, she says.

When we mitigate something, we reduce its severity or seriousness. With climate change, that could mean burning less oil, gas and coal. People might do this by conserving energy or switching to renewable sources of power, such as solar and wind. Many cities and countries around the world have started doing this.

For instance, Asseng at the University of Florida has studied what will happen to wheat as temperatures warm. The goal is to help scientists breed new crops that can tolerate heat better. Such breeding can take decades, which is why they have already begun.

To prevent mosquito-borne diseases from spreading, people can monitor imported tires and other goods for the insect’s eggs and larvae. They also can create good health-care systems to take care of people when they get sick.

Before long, many homes and businesses may have to be moved away from coasts, where they are vulnerable to sea level rise. Already, some Alaskan coastal towns are moving inland. And cities and countries may need to better prepare for more severe weather, such as floods and droughts. New York City, for example, has ranked six zones for their risk from damage during a future hurricane with the strength of Sandy. There are plans to evacuate those zones if needed. That won’t prevent buildings from getting damaged. But it could save lives.

Schools are especially good places to start finding climate-change solutions, Hellman says. “They are hotbeds for trying out sustainability ideas that can be rolled out into the community afterwards.”

Word Find (click here to enlarge for printing)