Cool Jobs: Studying what you love

Researchers study the same animals that fascinated them as kids

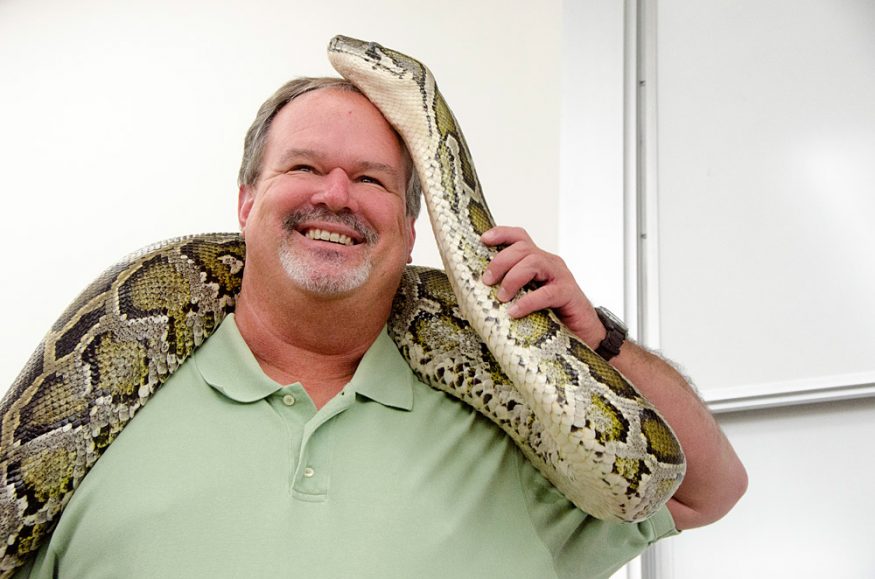

Biologist Michael Dorcas loved snakes when he was a kid. Now he studies amphibians and reptiles, including Burmese pythons like the one he’s holding.

Davidson College

By Roberta Kwok

Wayne Maddison was 13 years old when he fell in love. Standing on the shore of Lake Ontario in Canada, he noticed a mat of grass float by. On top of the mat was a spider about the size of a dime, with metallic green jaws. “She looked up at me,” recalls Maddison. “So of course I looked down at her and I thought, Wow!” Intrigued by her looks, Maddison wanted to know more about this colorful species.

Maddison took the spider home, fed her and named her Phiddy. When she later laid eggs, Maddison raised one of the babies. Before long, he was looking for more spiders and drawing pictures of them. Today, Maddison is a biologist at the University of British Columbia in Vancouver, Canada, where he studies spiders full-time. He even travels to remote jungles around the world, searching for new species.

Maddison is not the only scientist who has turned a childhood pet into a research career. Michael Dorcas, like many herpetologists — scientists who study reptiles and amphibians — was that 10-year-old kid who could usually be found nestling some snake in his pocket. Now a scientist at Davidson College in North Carolina, “I have figured out how to do as an adult what I enjoyed doing as a kid,” he says: catching and studying snakes.

Here’s a look at three scientists who are lucky enough to spend their adult lives working in fields that first captivated them in childhood.

Spider explorer

The spider that Maddison saw on Lake Ontario was a jumping spider. These spiders have eight eyes: six that look around in different directions and two that look straight ahead. The spiders jump from leaf to leaf. When they find prey, such as a beetle or an ant, they pounce on it like a cat.

Maddison likes jumping spiders because of the way they react to their world. Like humans, the spiders rely a lot on vision to sense their environment. For example, a jumping spider may turn to look at something moving by. With most other spiders, it’s hard to tell what they’re thinking because they navigate using other senses such as touch or taste, says Maddison. But with a jumping spider, he says, “You feel as if you can get inside its head.”

After Maddison got interested in jumping spiders, he bought a field guide and started looking for spiders on family trips. He made detailed drawings and learned how to examine spiders under a microscope. He wrote letters to scientists who studied spiders, requesting copies of their articles or asking for help identifying a species that was new to him. He even visited university professors to chat with them about jumping spiders.

In college, Maddison majored in biology and during the summers worked at a museum. He used the museum’s microscopes to study spiders during his lunch breaks and drew spiders over the weekends. “I just kept going deeper and deeper into it,” he says. “I didn’t wait for somebody to tell me what I should do.” Eventually, Maddison attended graduate school, where he studied spiders full-time.

Now, Maddison travels around the world in search of new spiders. He has explored tropical forests in Ecuador,Malaysia,Gabon,Papua New Guinea and the Caribbean. About half the species his team collects have never been described by scientists before.

During a trip to Ecuador in 2010, Maddison shook a vine growing up a tree. A tiny spider fell out, and Maddison realized at once that it was a new species. The spider had a yellow stripe across its face that looked like a moustache. Because the moustache made the spider resemble a Dr. Seuss character called the Lorax, Maddison plans to name this species Lapsias lorax. Last spring, Maddison traveled to the island of Borneo in Malaysia, where his team found more than 150 species of jumping spiders. (Along the way, he also was bitten by leeches and stung by a wasp.)

Back in the lab, Maddison studies spiders to understand their behavior — in particular, how the males court females. He’s witnessed males performing elaborate dances to attract mates.

He also writes computer programs to analyze spiders’ DNA. These programs help him figure out how closely related different spiders are to one another.

“There’s a side of me that has written 100,000 lines of computer code, and another side of me that tromps through the jungle,” he says. Both help him better understand the eight-legged critters that he’s studied for more than four decades.

W. Maddison, Beaty Biodiversity Museum

Soft spot for snakes

Dorcas first became interested in snakes when he found them during camping trips. He started keeping snakes as pets in his family’s pool house, sometimes as many as 30 at a time. “I basically turned it into my own little reptile house,” he says. He spent hours watching his snakes and recording their behavior.

When he was a teenager, Dorcas started volunteering at a nearby zoo. He spent a lot of time cleaning cages. But along the way, he learned more about the animals. “It was so cool,” he says. “I was working at this place that I’d gone to all my life, and it was just the best place in the world.”

Dorcas didn’t initially think he would become a scientist. He told himself that was something that only “really, really smart people” did. But after finishing a biology degree and working in a university lab studying rattlesnakes for a few years, he decided to keep going. So he pursued a doctoral degree at Idaho State University in Pocatello, where he studied a snake called the rubber boa.

Today, some of Dorcas’ research focuses on one of the biggest snakes in the world: the Burmese python. This constrictor grows up to 6 meters (about 20 feet) long and can weigh several hundred pounds. It can swallow alligators and deer whole.

A few decades ago, some Burmese pythons entered Everglades National Park in Florida. The Asian species might have escaped from pet owners or even been deliberately released. No one really knows how many Burmese pythons now live there. But wildlife biologists guess that there may be tens of thousands of these snakes living in the Everglades— most of them born there.

As part of their research on this python invasion, Dorcas and his colleagues drove along park roads, counting snakes and other animals. The first time Dorcas saw a Burmese python in the Everglades, he was so excited that he jumped out of his car and forgot to put it in park. His student had to hit the brake “to keep me from getting run over,” he recalls.

On such treks, Dorcas and his colleagues noticed that some formerly common animals seemed very scarce. At one point, Dorcas realized, “I’ve been doing this for years and haven’t seen a single raccoon.” So he and his coworkers decided to see if they could calculate whether this was a trend.

The biologists compared the number of animals seen during road surveys from the last decade to numbers recorded by a scientist in the 1990s (before pythons were known to be breeding in the wilds of Florida). The researchers found that the number of animals seen per 100 kilometers (about 60 miles) of roadways had dropped by 99 percent for raccoons and opossums, 94 percent for white-tailed deer and 88 percent for bobcats. The explanation: Pythons ate a lot of them.

To stop pythons from doing so much damage, federal regulators began programs to find and kill the snakes. The idea makes Dorcas sad. But “it also makes me sad to know that Everglades National Park is not as natural as it used to be,” he says. As adults, these foreign snakes have few natural predators in the United States. So other animals are now suffering because humans brought Burmese pythons to the Everglades. “We have a responsibility to take care of the world,” Dorcas says. And that can mean attempting to wipe out — or at least control — populations that are overtaking a new environment.

From dinos to crocs

Paul Gignac liked drawing dinosaurs when he was a kid. But “they never looked right to me,” he says. So Gignac started reading books about dinosaurs to improve his pictures. He found fascinating stories about scientists who spent months in the field digging up old bones. “It just sounded like the greatest way to spend your life,” he recalls.

In high school, a program called the JASON Project got Gignac even more hooked on science. The program allowed him to travel to Yellowstone National Park and do interviews with researchers that were broadcast on live satellite TV to students around the world. Once Gignac got to college, he worked in a lab that studied reptile feeding. He investigated whether different jaw types in lizards affect the way the animals catch prey.

Gignac was still intrigued by dinosaurs, however. So he asked dinosaur researchers if he could join them in the field. One summer, he helped search for fossils within the badlands of Alberta, Canada. There, he was part of a team that identified bones from Edmontosaurus, a duck-billed dinosaur that lived roughly 70 million years ago.

Wondering whether he could bring his interests in feeding and dinosaurs together, Gignac began working in the lab of Greg Erickson at Florida State University in Tallahassee. Erickson studies feeding in crocodilians, reptiles that include crocodiles and alligators. Dinosaurs and crocodilians descended from the same animals. So by studying crocodilians, Gignac reasoned that he and others might also learn something about dinosaurs.

On Gignac’s first visit to the lab, Erickson took him to a zoo and research center with a lot of crocodilians. Gignac climbed on the back of an alligator and held the animal’s head. Meanwhile, Erickson put a device in the alligator’s mouth to measure how hard the animal could bite. “It was a super thrill,” says Gignac. He was too excited to be scared, he says.

In a study published this year, Erickson, Gignac and other researchers measured the bite forces of all 23 living crocodilian species. In almost every case, they found, an animal’s size determined its bite force. The bigger the animal, the harder it could bite.

One species, the saltwater crocodile, could bite harder than any animal ever measured. The researchers used such measurements to estimate that an enormous, extinct alligator-like animal called Deinosuchus riograndensis — which grew up to 12 meters (almost 40 feet) long and lived about 73 million years ago — could probably bite about twice as hard as Tyrannosaurus rex.

Gignac has also studied dinosaur fossils. In one project, his team analyzed bite marks that a dinosaur called Deinonychus antirrhopus left on the bones of its prey. Gignac’s father, a dental technician, made a replica of a dinosaur tooth. Gignac used the model tooth to estimate how hard Deinonychus could bite — about as hard as an African lion and harder than a wolf, tiger or polar bear.

Gignac now works at the Stony Brook University School of Medicine in New York as a paleobiologist, someone who studies living animals to better understand extinct ones. This summer, he will travel to Madagascar to search for fossils of crocodiles, dinosaurs and other creatures.

Gignac, Maddison and Dorcas got where they are by following their interests and talking — sometimes even as children — to many experts in the field. “Learn everything you can on your own,” says Maddison. But, he recommends, also “make contact with other people that also have the same passion.”

And don’t be shy about asking researchers, teachers, friends and family members for help developing your interest. “We’re always looking for the next generation of scientists,” says Gignac.

Maddison records the behavior of a newly found jumping spider in Ecuador in late 2010.

Power Words

DNA The genetic instructions inside cells that tell them which molecules to make.

herpetologist A scientist who studies reptiles and amphibians.

fossil The preserved remains of an organism, or the impression left by an organism in a material such as rock.

crocodilian A group of reptiles that includes crocodiles and alligators.

paleobiologist A scientist who studies the biology of living animals to understand the biology of fossil animals.

This is one in a series on careers in science, technology, engineering and mathematics made possible by support from the Northrop Grumman Foundation.