Catching sports cheaters with a doping detector

Two teens are out to detect doping athletes before they cross the finish line

Some athletes use drugs to boost their performance. Two teens decided to find a fast way to detect these cheaters.

Vonschonertagen/iStockphoto

PITTSBURGH, Pa. — Athletes are competitive. They have to be. But sometimes, that will to win goes too far. They may cheat by taking drugs to improve their performance — an illegal tactic known as doping. Scientists have developed tests to stop them. But most only identify cheaters after a sporting event is over. Yagmur Akyaz, 18, and Semiha Doga Firat, 18, wanted a way to detect doping before a competition. Three weeks ago, they unveiled a small, inexpensive kit. They report that it can detect two doping drugs with the help of little more than a smartphone.

Both teens are seniors at Takev Science High School in Izmir, Turkey. The two also are passionate volleyball players. “We are both very interested in sports,” says Yagmur. But the teens had become frustrated with the degree of doping showing up at competitions.

“Doping in today’s world is a huge problem,” Yagmur notes. “Even the most famous athletes have been accused of doping.”

Most tests for performance-enhancing drugs analyze an athlete’s blood, saliva or urine. But the tests tend to be slow. Results often won’t come back until well after an athlete has competed. If it turns up evidence of doping, athletes might lose any awards they won. The sport clubs these athletes belong to might be fined huge amounts of money. Countries with cheating athletes might even be barred from future events, such as the Olympics.

But catching cheaters at this later date may still have allowed an athlete to have received undue praise, depriving others of their chance to get their medal in the spotlight. “Our aim was to develop a test system to get results immediately and on site,” Yagmur notes.

The test that she and Semiha created takes about 10 minutes to run. That’s fast enough to test everyone on a team before a game starts. And when the teens compared their test to others on the market, it performed just as well. Their test also was less costly. Several dozen people could be screened for a total of $40 to $50, “which is way less than [tests] used today,” Yagmur says.

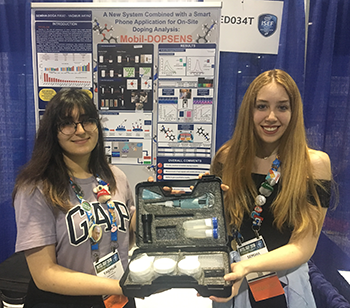

She and Semiha showcased their new test here, at the Intel International Science and Engineering Fair (ISEF). This yearly event brings together almost 1,800 students from 81 countries. The finalists share their science fair projects with the public and compete for about $5 million in prizes. The fair was created and is run by Society for Science & the Public, and is sponsored this year by Intel. (The Society also publishes Science News for Students and this blog.)

Designing a doping detector

The pair worked with Suma Timur. She is a biochemist — someone who uses chemistry to find out how cells function — at Ege University in Izmir. The teens decided to adapt a test known as an ELISA. It that can detect very small quantities of some target chemical in a liquid.

The test uses antibodies — tiny molecules designed to attach to a specific chemical, such as a doping drug. When combined with a liquid (such as saliva or urine), the antibody latches onto any of the target compound. To see whether it’s there, the teens add a second liquid. This one attaches to the antibody — “tags” it — to make it glow.

The result is a test that tints a clear liquid when a doping agent is present. Using a smartphone, someone can snap a picture of the colored liquid. They can then compare the color to other colored samples where the amount of drug was already known. The color tells the teens how much drug is in the saliva or urine — and in the athlete.

Yagmur and Semiha tested their technique on two drugs that football (soccer) players commonly use in Turkey: cocaine and methamphetamine (or meth). Both drugs are addictive. Scientists have shown each can also stimulate the nervous system, allowing athletes to briefly run faster and focus better.

If cocaine is present, the new test glows bright pink. Where the sample contains meth, the liquid turns blue.

Right now, the teens’ new test works only for these drugs. They do plan, however, to develop the ability to test for more. “We want to work with steroids and substances frequently used in America, India and Japan,” Yagmur says. The students also want to develop their own special phone app that will be specific to the test, instead of using a general photo app.

Most of all, the young women are determined to stop doping. Drug use doesn’t just alter someone’s performance, Yagmur says, it also can harm health. Athletes in Turkey, she explains, often don’t realize what the doping drugs’ impacts might be — such as their potential to cause serious health issues, even death.

On the social level, drug testing also is about fairness. If an athlete wins some competition, Yagmur says, “it should be because they’re working harder” — not because they’re doing drugs.