What is trendy in today’s science fair projects?

We analyzed more than 19,000 science fair projects to find out

Entrants in today’s science fairs are performing research in university labs and also doing award-winning work from home.

StefaNikolic/ISTOCK/GETTY IMAGES PLUS

WASHINGTON, D.C. — When most people consider a science fair, they might think of baking soda volcanoes and model rockets. But these days, you’re far more likely to find new smartphone apps and computer programs. What’s hot and what’s not? We decided to crunch the data from the past 10 years of the Regeneron Science Talent Search to find out. It turns out that the key to finding a science fair project is sticking close to home.

The Science Talent Search, or STS, is arguably the premier U.S. science competition for high school students. And it has been almost since its founding in 1942 by Society for Science and the Public. (STS is now sponsored by Regeneron, a company that makes medications to treat diseases such as asthma and cancer.) Any U.S. high school senior can apply to STS. This year, nearly 2,000 did. Among the many items that entrants had to submit to qualify was a science-research project.

But there wasn’t a baking soda volcano in the bunch. Science has changed a lot in the last 77 years. We’ve gone from the space race and landing an astronaut on the moon to mapping the DNA blueprint of our species and many others. In the last 10 years, smartphones have put a camera and computer in nearly everyone’s hands. A simple home computer can now analyze big data from exoplanets millions of light-years away.

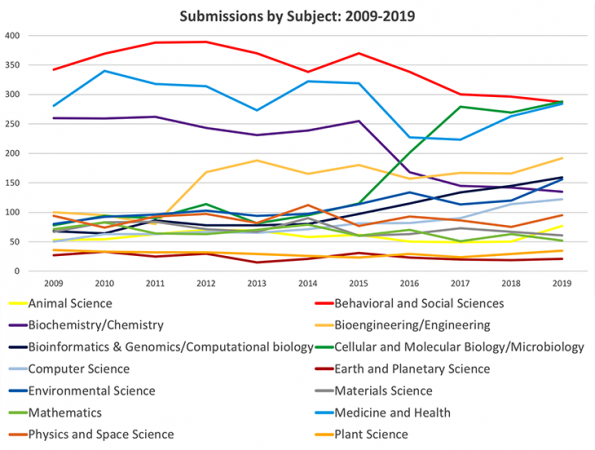

And as science changes, science projects may, too. When it comes to the STS candidates, which topics have proven most popular? Science News for Students is run by the same organization as STS. So to answer this question, we dug into 10 years of data and almost 20,000 project submissions. The results have been graphed here.

Article continues below graph.

Not surprisingly, the data show that the popularity of topics can shift widely over time.

Teens choose which category their project falls under, explains Alison Hewlett Stifel. She directs the competition. What topic they choose determines the type of scientist who will end up seeing their application first.

Say a teen’s project is both about plants and the environment. They might want to select “plant science” and know that a plant scientist will see it first. If they instead select “environmental science,” that’s the type of scientist who will take an initial read of their application.

It’s been a long time since the glory days of the space race. The most popular category now, by far, is behavioral and social sciences. Students working in these fields might study anything from how robots read emotions to techniques to shut down bullying.

The next most popular category is medicine and health. Here, teens might work in a laboratory with adult scientists to study new some new drug to treat a disease such as cancer. But they also might stay at home, developing a smartphone app to diagnose a particular disease. (Don’t think you need to study these most-popular topics to win, though. This year’s winner was an exoplanet hunter.)

Throughout the past decade, the number of engineering projects has gone up, Hewlett Stifel notes. There’s also been a big recent spike in cellular and molecular biology projects. Plants and Earth science, however, aren’t very popular topics. Both of those categories each bring in fewer than 40 STS applications per year — only about two percent.

Sudarshan Chawathe chaired the judging panel for this year’s STS competition. Although a computer scientist at the University of Maine in Orono, he feels sad to see so few plant science projects. “I guess it’s not considered sexy enough anymore,” he says. “It’s really sad for me. I think there’s so much interesting stuff there.”

The trend away from plants and toward medicine, health and engineering reflects more than teen interest, he says. It also reflects trends in research, generally. “This is guesswork,” he says, “but it would be hard to imagine that [teens] aren’t affected by [the work that mentors are up to].” A teen may work in a lab that has money to study cancer or HIV. “So they study cancer or HIV,” Chawathe notes. STS and science fair submissions, he says, likely “reflect what’s going on broadly in the scientific community.”

Unfortunately, it’s hard to tell from the STS data exactly what teens would most like to study. But in her eight years working with the competition, Hewlett Stifel has observed a few trends. “Smartphone technologies are really interesting to teens,” she says. “It’s something personal to them.” She and Chawathe also noticed that increasingly teens are mining large, public data sets — from cancer data to exoplanets — to inspire their projects.

That means that many teens can do big science from home. They no longer need access to some lab at a nearby university or a study site. The real thing that inspires strong teen research, Hewlett Stifel finds, are issues, problems and questions that affect young scientists, their communities and their curiosity.

Smartphones, powerful computers and free access to meaningful data mean that more students can find new solutions to scientific mysteries.