New forensic technique may better gauge age at death

Used with skulls, the estimates should fall within three years of an adult’s actual age

Andrey Gizdov, 18, came up with a new and potentially better way to estimate the age at death for human remains. It’s based on a CT scan of the person's skull.

Kyle Ryan/SSP

By Sid Perkins

PHOENIX, Ariz. — When detectives analyze human remains, they often have many questions. One of the most common: How old was the person at death? A teen in Ackworth, England has developed a new way to figure that out. And it may be more accurate than techniques typically used today.

Estimating the age of unidentified human remains is difficult, notes Andrey Gizdov, an 18-year-old who attends the Ackworth School. Because the skull usually remains intact, forensic experts currently use several techniques that focus on these bones to gauge skeletal age. The techniques often focus on cranial sutures (KRAY-nee-ul SOO-churz). These are seams where individual bones in the skull meet and merge. As people age, these seams continue to fuse ever more strongly — even in mature adults. That underlies Andrey’s new technique.

The teen showcased his research here, last week, at the Intel International Science and Engineering Fair. This competition was created by Society for Science & the Public in 1950. Its 2019 event brought together more than 1,800 finalists from 80 countries. (The Society also publishes Science News for Students.)

Andrey’s technique homes in on details present in X-ray images that are created by computerized tomography, also known as CT. This technology scans an object or body part. The resulting X-ray images look like hundreds of sequential slices through the object. A computer merges those images into a file to create a digital 3-D model of the scanned object. A computer can then display any cross-section of the object and from any angle.

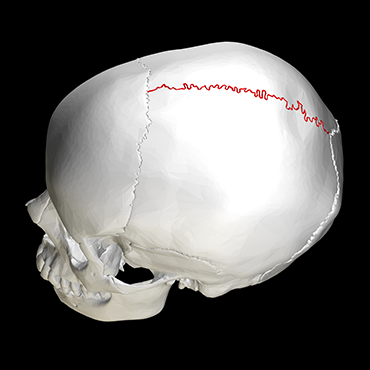

For his project, Andrey reviewed skull CT scans that had been performed by others. He focused on a structure known as the sagittal suture. Along the centerline of the skull, it runs from the top of the forehead back to the crown of their head. Up close, that seam resembles a meandering river.

The CT’s X-rayed slices of this suture were about a millimeter (1/25th of an inch) thick, Andrey says. For an adult skull, there would be some 350 or so sequential images available to analyze. In most of these, the suture showed up as a V-shaped notch between the bones, explains Andrey. Think of the bottom of the V as a valley. As a person ages, that valley gradually fills in with calcium-based minerals. Usually, it fills in from valley floor up toward the top.

Andrey used computer software to analyze each image. The software measured how deeply the V-shaped notch had filled in with minerals. He also used the software to estimate the density of those minerals. (The darker the notch shows up in the scans, the less dense the bone is, Andrey notes.) Then, the teen took all of his measurements and calculated an average for both the depth and the density of minerals along the entire suture.

He did this for the sagittal suture in 42 skulls. Each came from known persons. Their ages at death — from 19 to about 60 — also were known. By comparing the sutures, he showed that this feature changes with age. Andrey then used those 42 data points to develop a mathematical equation. It related age at death to the depth and density of calcium minerals in the sagittal suture.

The teen then used his equation to predict the age at death from skulls of other people. Their ages at death, too, were known. He typically was able to estimate a person’s age at death to within 3.2 years. That’s a big improvement over current methods. Currently, he notes, researchers usually can estimate age at death only to within 10 years.

One day, Andrey’s technique might help archaeologists analyzing ancient remains. Still, the technique isn’t perfect. After all, everyone ages differently. Plus, other factors might affect how quickly and how well someone’s sagittal suture fills in with minerals. For instance, suffering from malnutrition might alter suture filling, says Andrey. So might certain diseases, such as osteoporosis (Os-tee-oh-por-OH-sis), which weakens bones.