Teen finds more graphic heroines are ‘super’

A study of comics history shows women getting more independent and powerful over the last 50 years

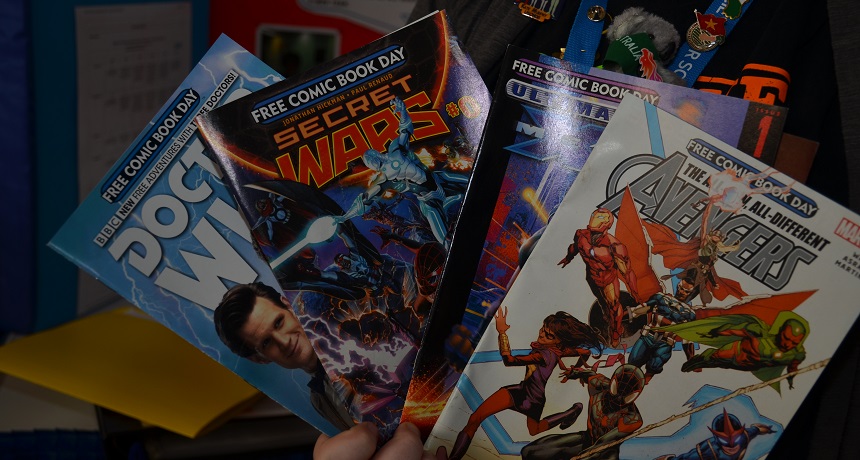

Over the years, women have become better represented in comics, with more power and responsibility, a teen scientist shows.

L. Buitrago/SSP

PITTSBURGH, Pa. — Many people like to use comics to discuss science. All over the Internet, you can find articles explaining the physics behind Thor’s hammer or what real-life X-Men might be like. But one teen scientist decided to apply science to comics. Her research probed how women are portrayed in comics. And over time, women in the Marvel comic books are more often portrayed as equal to men, she now demonstrates.

Katherine Murphy, 17, showed off her findings at the Intel International Science and Engineering Fair, a competition created by Society for Science & the Public and sponsored by Intel. The junior at Hicksville Exempted Village High School in Ohio was among some 1700 students from more than 70 countries to present their science fair projects. (SSP also publishes Science News for Students and this blog).

“I absolutely love comics,” Katherine says. When she had trouble grasping phonics and phrases in kindergarten, the combination of pictures and words in comic books helped her learn to read. As she grew older, Katherine realized how media such as comic books influence the way people think. “People who grow up reading comic books absorb things in comic books,” she explains. “If the things in the comic books are toxic, such as the way people treat women, then [readers] absorb that.”

So Katherine thought, “‘What if I did a science project about how women are shown in comic books?’” The teen admits “I’m not a huge science person. But I like comic books and I am really into women’s rights.”

Katherine was lucky to live near Bowling Green State University in Ohio. The university has a popular culture library that is full of recordings of TV shows, novels and comic books. So every Sunday, the teen headed there to read comics from Marvel Entertainment, LLC. It’s the brand responsible for the Avengers, Spiderman, X-Men and more.

A helpful graduate student at Bowling Green randomly picked comic books from Marvel for the teen to read. The earliest was from 1961; the latest was from 2014. Katherine focused on seven different criteria, and ranked each on a scale from one to five. Was a woman on the cover? How did the female characters look? Did women in the comic book talk to each other about important issues? Was the storyline about a woman? Were women in positions of power? Did they make their own decisions? Did they have jobs?

The maximum score that any one comic could earn was 35. After reading 788 comics from 68 different Marvel titles, Katherine showed that over time, women have become more powerful, are involved in more important issues and get more cover art. While the average score in the 1960s was 12.2, by 2014 it had nearly doubled to 22.5.

Katherine hypothesizes that one reason those scores might be rising could have to do with who is developing and reading these books. “Marvel has more women writing for it, more women drawing for it and more women reading [comics],” she explains. Female readers want to see women represented equally, the teen says, so comics publishers have been delivering that.

Follow Eureka! Lab on Twitter

Power Words

(for more about Power Words, click here)

graduate student Someone working toward an advanced degree by taking classes and performing research. This work is done after the student has already graduated from college (usually with a four-year degree).

hypothesis A proposed explanation for a phenomenon. In science, a hypothesis is an idea that must be rigorously tested before it is accepted or rejected.

Society for Science and the Public (or SSP) A nonprofit organization created in 1921 and based in Washington, D.C. Since its founding, SSP has been not only promoting public engagement in scientific research but also the public understanding of science. It created and continues to run the Intel International Science and Engineering Fair (initially launched in 1950). SSP also publishes award-winning journalism in Science News (launched in 1922) and Science News for Students (created in 2003). Those magazines also host a series of blogs (including Eureka! Lab).