Churk: Not for Thanksgiving

Here’s what happens when livestock breeders cross a chicken and a turkey

GlobalP/iStockphoto; modified by L. Steenblik Hwang

By Janet Raloff

More than a half-century ago, researchers outside Washington, D.C., engaged in some creative barnyard breeding. Their offices were at the Beltsville Agricultural Research Center. And their goal was the development of fatherless turkeys — hens whose eggs would hatch without being fertilized by a tom. Along the way, and quite by accident, an interim stage of this work resulted in a “churk.” Or that’s the scientists’ term for a hybrid that had a chicken for a father and a turkey for a mother.

The creatures were literally twisted. They had crooked legs, beaks and feathers.

Adding insult to injury, the churks were only half as smart as their parents, according to Marlow Olsen. He’s the scientist who headed the fowl research project.

It would be tempting to call this bird an ugly chuckling or a pathetic gobbler, except that the hybrid remained largely silent — unless disturbed. Then it emitted a puny, chickeny chirp.

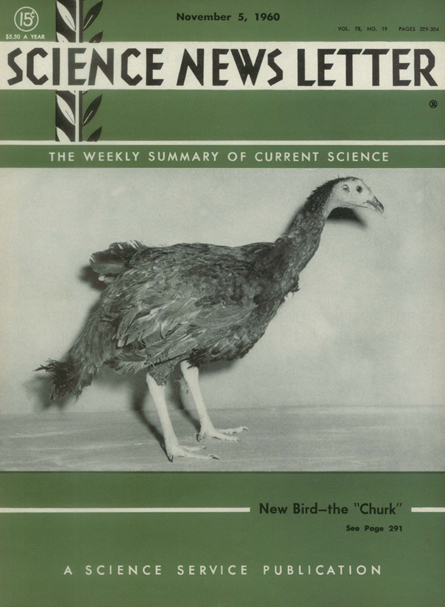

But that didn’t prevent Science News from crowing about the animal as a “history-making cross” in its November 5, 1960, cover story. The story billed it as “the first known hybrid of two families of birds.”

The text also suggested why we’d hear little more about the animal. The hybrids were all male, so they couldn’t reproduce. The offspring proved devilishly difficult to nurture, even just to hatching. The three Beltsville birds that lived to seven months of age were the sole survivors of 2,900 eggs that the scientists had fertilized using sperm cells from a male chicken.

Olsen was not the first to encounter trouble while creating a chicken-turkey hybrid. A 1960 paper he authored in the Journal of Heredity cited a reference to 12 previous trials. None had resulted in a single hatchling. Several additional reports claimed to produce a few live young, he says, but offered no details. Part of the problem likely traced to a dramatic mismatch of the parents’ genes.

Chromosomes are threadlike structures in each cell that carry the genes that pass on inherited traits. Chickens possess six pairs of chromosomes. Turkeys have nine. Each offspring receives one-half of each chromosome pair from its mom and its dad. That should result in a newly matched pairing of traits from each parent. Except that the 15 chromosomes that each hybrid started with had no chance of pairing appropriately into six chromosomes like dad’s, nine like mom’s — or any other number in between.

That appears to explain the sickly offspring.

Mother Nature, however, has created what looks like a healthy chicken-turkey hybrid: the colorfully named Transylvanian naked neck chicken. The difference is that there are no turkeys in this bird’s ancestry.

As its name implies, this breed has featherless necks. “We initially worked on identifying the mutation that causes the naked neck trait in chickens, as we are interested in understanding how patterns arise,” explains Denis Headon. He works at the Roslin Institute and Scotland’s University of Edinburgh’s Royal School of Veterinary Studies. His team traced the trait to where “part of chromosome 1 had moved across to chromosome 3 and inserted,” he says. Follow-up studies, Headon adds, showed that genes make the neck skin of these birds especially susceptible to losing the ability to produce feathers.

Naked-necked chickens of various types occur around the world. In some parts of the Middle East, Africa and Asia, Headon speculates, this could develop because such chickens “are more tolerant of heat than are fully feathered chickens.”

As for Transylvania as the birds’ ancestral home: “This seems quite unlikely,” he says. “Domestic animals often have geographically misleading names (the turkey itself being a great example).”