Explainer: Ice sheets and glaciers

Here’s how and where these ice blankets form

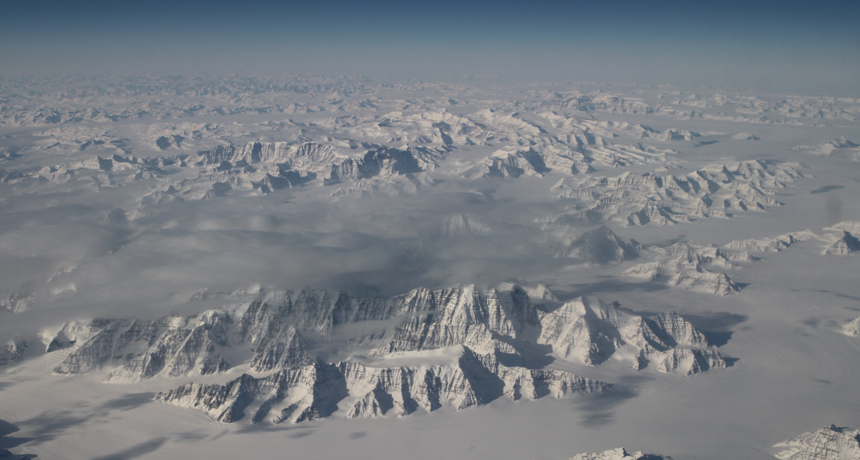

A view of an Greenland ice sheet from 40,000 feet above. Scientists are using planes and satellites to study how ice sheets and glaciers are changing around the world.