biological clock A mechanism present in all life forms that controls when various functions such as metabolic signals, sleep cycles or photosynthesis should occur.

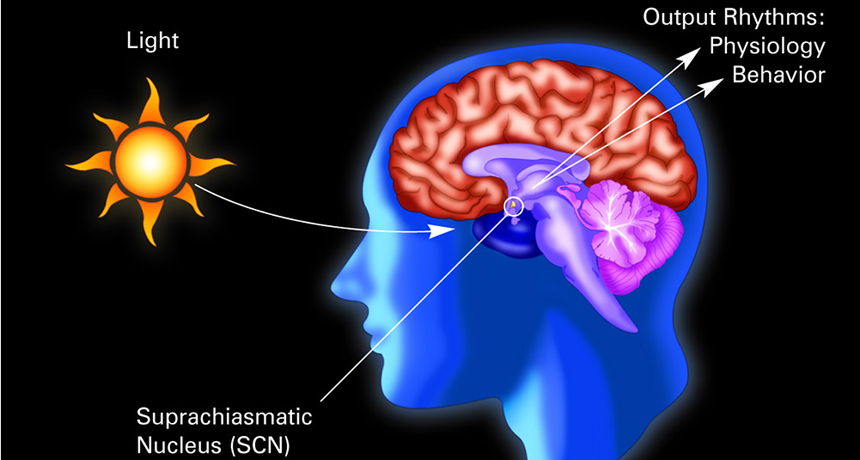

circadian rhythm Biological functions such as body temperature and sleeping/waking times that operate on a roughly 24-hour cycle.

hormone A chemical produced in a gland and then carried in the bloodstream to another part of the body. Hormones control many important body activities, such as growth. Hormones act by triggering or regulating chemical reactions in the body.

jet lag A temporary disruption of bodily rhythms caused when someone travels across several time zones in a matter of hours.

metabolism The set of chemical reactions that maintain life in living cells.

retina A light-sensitive layer of tissue that lines the back of the eye.