Fuzzy future

Kids may suffer impaired vision from spending too little time outdoors, studies suggest

Many scientists today are finding that too much time spent indoors — at least during childhood — may affect vision, making it hard to see distant objects clearly. Doctors refer to this nearsightedness as myopia. Studies have found that kids who regularly spend time on computers have an increased risk of being diagnosed with myopia.

iStockphoto

By Nathan Seppa

Rogers Hornsby was the Derek Jeter of the 1920s. Actually, Hornsby could hit a baseball better than Jeter — he just wasn’t as popular. Teammates complained that Hornsby didn’t like to hang out with them. He didn’t go to see movies, which was surprising because 90 years ago that was primo entertainment. Hornsby said that sitting in a dark theater watching a bright screen made it difficult to hit a baseball. Hard to argue with a guy who reportedly had terrific eyesight and who batted over .400 in three seasons.

As it turns out, Hornsby might have been onto something. Many scientists today are finding that too much time spent indoors — at least during childhood — may affect vision, making it hard to see distant objects clearly. Doctors refer to this nearsightedness as myopia.

In recent decades, more and more people have found they need glasses or contact lenses to correct for nearsightedness. Rates are rising especially fast in children.

Today, 1 in 3 U.S. adults is nearsighted. The rate is slightly higher among the younger adults. And in East Asia, the trend is downright alarming. More than 95 percent of young men in Seoul, South Korea, and college students of both genders in Shanghai, China, are nearsighted, new studies show. That’s 19 out of every 20 individuals!

Many researchers were stunned when they first saw these rates. And they were just as surprised to hear some scientists blame the problem on spending too much time indoors. The notion that recess might promote better vision seemed almost magical.

“Certainly, before five years ago, I don’t think anybody had taken much notice of how much time people spent outdoors,” says Jeremy Guggenheim. This optometrist has studied nearsightedness in Great Britain and Hong Kong. (An optometrist is trained and licensed to examine eyes for defects and to prescribe treatment or corrective lenses.)

Guggenheim says it is not yet clear by how much outdoor exposure can lower a person’s risk — or even how it would do so. Some scientists say it could be a mix of three things: exposure to natural light, resting the eyes by viewing things far off, or reduced visual clutter in the corner of the eyes.

Other behaviors might matter, too. The flood of nearsightedness today is showing up in a generation of children and college kids raised on computers and video games. Especially in the Far East, many children do lots and lots of schoolwork. A theory that too much reading or other “near work” fosters nearsighted vision has given rise to a term for today’s youth of “Generation Specs.” (Specs is short for spectacles, an old-fashioned term for eyeglasses.)

Without doubt, the cause of this increasing myopia remains fuzzy. But in the city of Guangzhou, China, an experiment is under way. There, some third-graders have been assigned to spend an extra hour outdoors every day. Although it sounds like more recess, scientists are already finding that these children have slightly better vision.

Squint city!

The human eye is a fine-tuned gizmo and it doesn’t take much to mess it up. Nearsighted people have a slightly elongated eyeball. Its being a tiny bit more egg-shaped than normal causes trouble. Elongated eyes can still focus clearly on nearby objects, but more images come to a focus at the wrong place within the eye. They focus slightly in front of the retina, which is at the back of the eye (see diagram). This sends the brain a blurry picture of anything but close-up objects — unless the viewer wears eyeglasses or contact lenses to refocus the images.

So what distorts the eyeball and causes this loss of focus?

Scientific evidence suggests the problem starts early because the eye grows steadily in childhood. That growth is fastest in infancy. But the eyeball continues to grow some into the teen years. Our genes, which carry the built-in instructions for every cell in the body, regulate much of that growth. But proper development of the eyes also depends heavily on what scientists call visual feedback. That’s the everyday effect of incoming light.

Scientists are now convinced that something about this visual feedback has changed in recent decades. And those changes appear to be driving an epidemic of nearsightedness among teens and young adults.

E. Feliciano

The share of nearsighted people over age 40 in China and the United States hasn’t changed much in the past few decades. It remains about 23 percent. That’s a lot less than the rate now seen in young adults of both nations.

What’s more, the growing trend in nearsightedness seems concentrated in people living in urban areas, such as cities and their suburbs. Rates in rural areas remain unchanged. That suggests the problem must trace to some new behaviors among young people in cities.

What’s the big deal?

Because most people have access to eyeglasses, nearsightedness may seem like just an inconvenience. But it could actually lead to serious health problems.

People who need strong corrective lenses run the risk of having worse vision when they get older. They face a heightened risk of getting cloudy vision (caused by what doctors call cataracts), elevated pressure in the eye (known as glaucoma) or potentially blinding damage to the eye (due to a detached retina). Among nearsighted college-age people in Seoul and Shanghai, roughly 1 in 5 are at risk of these other problems.

“There will be an epidemic of pathological myopia and associated blindness in the next few decades in Asia,” predicts Seang-Mei Saw. By “pathological,” she means unhealthy. Saw is a physician and epidemiologist at the National University of Singapore. (Like detectives, epidemiologists figure out what causes a particular health problem — and potentially how to slow its spread.)

Rising nearsightedness rates in recent decades prompted scientists to hunt for its cause. That brought the link between myopia and outdoor exposure into sharp focus.

In 2007, Donald Mutti, an optometrist at Ohio State University in Columbus, identified 514 children who were not nearsighted in the third grade. Over the next several years, 1 in 5 would go on to develop myopia. His team surveyed all the kids to see how they spent their time, indoors and out. The scientists found that kids who had spent more time outdoors doing physical activity were less likely to become nearsighted than were children who spent more time indoors. This trend held up even among children whose parents had been nearsighted.

A few decades ago, many researchers assumed myopia was mainly inherited from parents. After all, having one nearsighted parent adds some risk of needing glasses, and having two imparts more.

But genes passed on from parents don’t seem to explain the recent skyrocketing rate of nearsightedness.

Studies in 2010 and 2012 identified many unusual forms of genes that showed up more often in nearsighted people than in people with 20/20 vision. But Guggenheim says, “These are subtle genetic effects that explain only a small proportion of myopia.”

The new wave isn’t genetic, concludes Ian Morgan of the Australian National University in Canberra. “The gene pool can’t change that much in a generation, not even in several,” he says. “We’ve now got a very convincing new factor, and that’s time spent outdoors.”

In 2008, Morgan and Kathryn Rose of the University of Sydney, in Australia, linked nearsightedness to low outdoor exposure — in pre-teens. The Australians noted that playing indoor sports didn’t seem to affect myopia rates. Neither did reading nor performing other types of near work. What did make a difference: simply getting outside for hours each day.

Data from a new study adds more support for this idea. In Taiwan, an island country in Asia, researchers conducted a test on children in two elementary schools. In one, the kids were told to do whatever they wanted during recess. They could stay inside or go out. In the second school, all children were actively encouraged to spend every recess period outside.

About half of the children in each school had been nearsighted at the start of the year-long trial. By the end, an additional 18 percent of the kids in the school where students weren’t nudged to go outside had also become nearsighted. Among the kids who played outside every recess, only 8 percent more became nearsighted. The researchers in Kaohsiung, Taiwan, reported their finding in the May issue of Ophthalmology.

Infinity and beyond

Although nearsightedness has been treated — with eyeglasses — for hundreds of years, scientists still don’t completely understand what causes it. But some chemistry research supports the outdoor-light explanation.

Studies in animals show that bright light is a good thing because it triggers the release of a compound called dopamine in the retina. Dopamine is a signaling molecule. In the eye, it serves to limit inappropriate eye growth that can make the eye egg-shaped.

And the difference between light exposures indoors and outdoors isn’t even close. A sunny day delivers 32,000 to 130,000 lux, a measure of light intensity. But lighting inside the average house scores at less than 1,000 lux. A March 2012 study by the U.S. Department of Energy showed that the average lighting in rooms where people were watching TV was far lower — 50 lux or less in 8 out of every 10 rooms measured, and under 13 lux for one-third of the rooms.

Indoor lighting simply may not provide enough light to restrain inappropriate eye growth.

The eye is also in a more relaxed position outdoors, says Andy Fischer. He’s a biologist at Ohio State University who studies the retina. That eye relaxation may shut off growth signals, too, he says.

And compared with indoor viewing, outdoor exposures provide a different set of peripheral images, those seen out of the corner of the eye. And even peripheral images can be in or out of focus. Indoors, there’s a mix of focused and unfocused images coming from the periphery, as any glance around a kid’s bedroom will show, says Frank Schaeffel of Tubingen University in Germany. There are cabinets, a door farther away, a computer screen up close, you name it.

Being outdoors offers a field of vision that’s more uniform. It’s one that’s also more like our prehistoric ancestors’ view of the world. Throughout evolution, Fischer says, humans spent almost all their time outdoors. As a result, our eyes evolved to suit that environment. New behaviors — like living in an industrialized society and spending more time in classrooms — place unnatural demands on the eyes. These indoor behaviors may not mesh well with humans’ ancient genetic programming, he says.

Same with near work. Our Stone Age ancestors didn’t read. Even those who chipped arrow points or did other fine work probably didn’t do it all day, every day. Constant near work arrived only with civilization.

Recent work by Saw at the National University of Singapore and others has linked less outdoor exposure and more near work to nearsightedness. “Reading, writing and computer work contribute to myopia,” Saw says. “We found that children who regularly spend time on computers have a higher risk.”

So nearsightedness might be fostered by a combination of too much near work and too little outdoor exposure. After all, someone who reads a lot probably does it indoors; same with watching television or sitting at a computer.

Saturation point

Some scientists have seen enough. “We need to get the message out to parents,” says William Stell of the University of Calgary, in Canada. “Kick the kids outside.”

Ian Morgan agrees, but says it won’t be easy in some places. In Chinese schools, for example, children nap indoors for an hour or two at lunchtime. The idea is to let them rest up so that they can plow through hours of homework later.

And it might be hard to change this routine, he says. “When I floated the idea of stopping naps at lunchtime in China, the response was almost like I was advocating child cruelty,” Morgan says. Kids in North America and Europe may work hard, he says, “but you ain’t seen nothing until you’ve seen China.”

Even so, getting children outdoors might be easier than cutting back on near work, Saw says. The Asian educational system has reached a “saturation point” of intensity and competition, she says, but no one wants to tell children to read or work less.

In the United States, eye doctors are becoming aware of the outdoor-exposure theory. But many don’t see a child until after the kid has failed an eye exam at school, says psychologist Jane Gwiazda of the New England College of Optometry. That may be too late. “Once a child is nearsighted,” she says, “sending them outdoors to play may not stop the process.”

Short of getting out, maybe gazing out would help. It didn’t seem to hurt baseball player Hornsby. Asked once what he did all winter during the off-season, he snapped: “I’ll tell you what I do. I stare out the window and wait for spring.”

Power Words

20/20 vision This is the clarity of focus for images 20 feet away that are typical for people with healthy, unimpaired vision. Someone who instead has 20/100 vision sees only as well at 20 feet as people with normal vision would see at 100 feet, or five times farther away.

cataract A vision impairment caused by a cloudiness in a membrane that covers the lense of the eye. Uncorrected, it can lead to blindness.

epidemiologist Like health detectives, these researchers figure out what causes a particular illness and how to limit its spread.

glaucoma Eye disease that is the equivalent of hypertension: the pressure exerted by fluid inside the eye becomes excessively high. That pressure can damage the nerve carrying vision signals — and, if untreated, lead to partial or total blindness.

lux A measurement unit for the level of light.

myopia The medical term for nearsightedness.

nearsighted An inability to focus anything that isn’t nearby. It’s due to an elongation of the eyeball. Many factors can contribute to this inappropriate elongation, and so the cause of nearsightedness is still under debate.

neurobiologist Scientist who studies cells and functions of the brain and other parts of the nervous system.

optometrist In the United States, this is someone trained and licensed to examine eyes for defects and to prescribe treatment or corrective lenses. Although eye doctors, optometrists are not trained as physicians. Physicians who specialize in the eye are called ophthalmologists.

retina A layer at the back of the eyeball containing cells that are sensitive to light and that trigger nerve impulses that travel along the optic nerve to the brain, where a visual image is formed.

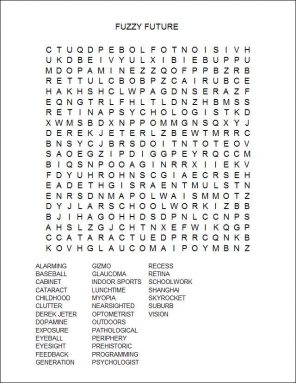

Word Find (click here to print puzzle)