Bats before bedtime

Scientists find new animal species in old rainforests

A mist net set up in the Iwokrama Forest’s understory snares a bat for scientists to study.

Andrew Snyder

By Hannah Hoag

Deep in the heart of a small South American country called Guyana lies a protected forest. As night falls, you will find this tropical rainforest pulses with life. It is anything but quiet. The whistle of a bird called the screaming piha pierces the thick canopy of trees, as if competing with the chorus of crickets, cicadas and mosquitoes. Other strange creatures make themselves heard too. A sheep frog bleats while red howler monkeys spookily wail from the treetops. On this evening, it seems no one in the rainforest is sleeping — including the scientist making his way down a narrow path.

Night is a great time to collect animals. To catch flying bats, it is also the only time. That is why Burton Lim is at work in the dark here in this forested region known as Iwokrama (EE WOE kram ah). It’s part of the greater Amazon ecosystem.

Some people call Lim the Bat Man. He’s a curator of mammals at the Royal Ontario Museum, in Toronto, Canada. Tonight, he forges into the dark rainforest to look for bats. He’s wearing a bright headlamp and rubber boots. A machete hangs from his belt.

Lim has come to the Iwokrama Forest because it is a hotspot for bats. Eighty-six species of them, roughly half of all the bats found across the Amazon, call this roughly circular zone of protected land home. The area is only about the size of Delaware. By comparison, the United States and Canada together host only 47 bat species.

Lim is on this expedition with a small team of scientists working with a conservation organization called Operation Wallacea. They’re here to study the rainforest’s large mammals, amphibians, birds, insects, reptiles and other animals. Luckily, a reporter for Science News for Kids is tagging along for part of the expedition. Exploring this richness of life, or biodiversity, lets scientists pinpoint areas that have rare or unique species. It also gives them clues useful in monitoring the health of this rainforest now — and in the future.

Good for everyone

Northern South America, which includes Guyana (and the Iwokrama Forest), has more biodiversity than almost anywhere else in the world. On land there are jaguars, giant anteaters and tapirs, or pig-shaped mammals with short, grippy snouts and thick splayed toes. More than 400 species of birds flit through the air here. In the water swim giant river otters and black caimans — large relatives of the alligator.

And everywhere there are insects. Some are so colorful they seem to have burst out of a paint box. Tangerine-, blond- and mint-colored butterflies flutter like confetti in the sun. Look up, and you might see a metallic-blue Morpho butterfly the size of a hand silently flapping from one tree to the next.

Tropical rainforests cover just one-seventeenth of Earth’s land surface. Still, they hold one-half to three-quarters of all of the world’s plant and animal species. All those species depend on one another. Forest plants provide animals with food and shelter. In return, animals help the plants reproduce. Bats, as well as birds, bees and other animals, spread pollen from flower to flower each time they slurp up nectar. Other animals, including not just bats and birds but monkeys, too, feast on fruit. Later, they spread seeds from that fruit throughout the forest each and every time they poop.

Biodiversity helps us too. It makes Earth a suitable place to live. The rainforest ecosystem can be a source of food, medicine and shelter for people, whether they live close by or far away. Most importantly, the forest also provides clean water and air.

“Rainforests are the largest contributors to the oxygen content in our atmosphere,” says Karen Redden, a botanist at the University of the District of Columbia. Redden collects plants across northeastern South America as part of her work for the Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of Natural History.

Rainforests also suck up carbon dioxide from the atmosphere and store it in their trunks and leaves. They reduce the amount of carbon dioxide, a greenhouse gas, available to build up in Earth’s atmosphere. Once in the atmosphere, that gas can trap heat and contribute to climate change.

A night in the rainforest

On this July night, deep in the rainforest away from the hum of a temporary field camp, Lim has set up 18 mist nets. They are below the treetops, in what is called the forest’s understory. The nets look a little like giant volleyball nets. Woven from fine black thread, they are hard to see. Buttons and camera straps easily get tangled in these nets. So do all kinds of bats.

In 2011, while working in the same area of forest, Lim caught 120 bats from 41 different species. The haul included two new bat species that no one had ever seen here before. “We had to use a sling shot to send special canopy nets up high into the trees to catch some of them,” he says.

A year later, the light from a headlamp bounces across the massive roots that fan out from the trunks of soaring trees. Vines as thick as a thumb wrap some of those trunks. And patrolling up and down those trunks are scorpions in glistening armor. Lim walks from one net to the next. He follows a transect — a straight path through the rainforest along which he will trap the bats. Tallying each type of bat will allow him to estimate the abundance of that species across the forest. Lim balances atop a fallen tree that blocks the route and jumps down onto the damp ground below.

Three bats are snarled but unharmed in the first net. One is a large, fanged bat with a leaf-shaped nose. It squeaks as Lim untangles it. “We once caught one of the biggest species of bat in South America at this site,” says Lim. That bat, the greater false-vampire bat, has a meter (roughly three foot) wingspan. It eats frogs, lizards, mice, birds and even other bats. However, the bat he collects tonight is a fruit eater. Lim slips the bat into a white cotton bag, cinches it shut and tucks it under his belt.

Collecting animals

People have been collecting and identifying plants, animals and other living things for hundreds of years. So far, scientists have given names to more than 1.3 million species. But there are many more that haven’t been named or even seen by scientists yet. Biologists think there are about 8.7 million species on Earth (and that is not even counting bacteria and viruses). Scientists and amateurs identify more than 18,000 new species each year.

Finding a new species is an exciting event — something that can happen fairly often in Guyana.

In 2006, Redden searched along the Potaro River, which flows through Guyana’s Kaieteur National Park. She was looking for a mysterious bean plant. Scientists had spotted the plant once in 1881 and again in 1958. But that was all. Redden spent five days hiking, climbing, sliding, boating and portaging during her search.

And then it appeared. She was awestruck because this is no ordinary bean. “Imagine Mother Nature could capture fireworks and put it on a flower,” says Redden. It had bright red petals, with long red filaments topped with black bobbles of pollen.

One evening during the Operation Wallacea expedition, a volunteer brought Andrew Snyder a glass frog. The tiny animal has see-through skin. Snyder is the expedition’s head scientist and a herpetologist from the University of Mississippi, in Oxford. A herpetologist studies amphibians, including frogs and salamanders, and reptiles, including snakes, lizards and crocodiles. Snyder couldn’t identify the glass frog — nor could his network of online experts once he posted photos to Facebook.

So he brought the frog back to Mississippi. There, he extracted DNA from the frog’s cells and stored it in a freezer. Soon Snyder will send the DNA to a laboratory that can spell out the genetic instructions it contains using a process called sequencing. That way, Snyder can read its genes and compare them to those of other known frog species. Could the frog represent an unknown species? “That’s my biggest excitement so far, but I’m trying to keep my excitement contained,” he says. “It may not turn out to be a new species.”

Quick . . . before it’s gone

Scientists keep finding new species in Guyana because it is so rich in biodiversity. The country also is largely unexplored — and for good reason. “The environment in Guyana’s interior is so harsh to get into and move around in,” explains Redden. As a result, “There’s a lot of stuff — plants, animals and insects — that hasn’t been collected.”

In many tropical countries, unlike Guyana, people have cut down large swaths of the rainforest to harvest timber or to carve out farms. When that happens, roads, mines and towns often follow. Drought, brought on by climate change, also has damaged Earth’s tropical rainforests.

All of these changes stress plants and animals, along with their habitats as a whole. Some rainforest species are on the brink of disappearing. Others have already gone extinct. It’s natural for some species to die out, but the current worldwide extinction rate may be 100 to 1,000 times greater than normal.

Jake Bicknell is a zoologist who wants to set up new protected areas in Guyana to preserve its biodiversity. Bicknell works at the University of Kent, in England. But he began doing research in Guyana nearly a decade ago. He organized the first Operation Wallacea trip to Guyana in 2011. These rainforest surveys will keep tabs on species diversity — the variety of animals. These surveys will also tally an animal’s relative abundance — whether it’s common or rare. Any changes could signal a species is under threat.

Currently, Guyana protects 8 percent of its rainforests from development — farming, the creation of towns or other human transformations. But it needs to double the protected area by 2020. “We want to identify areas that are important to biodiversity and are threatened by development,” says Bicknell. “I want to ensure that development takes place in the most environmentally sustainable way. Let’s minimize the effect on biodiversity.”

Animal monitors

Meanwhile, on this July night, Lim collects all the bats from his 18 mist nets and heads back to the field camp. There, he will measure and weigh each bat. He will also identify each by species. The careful records Lim keeps on bats can also give a picture, or indication, of the health of the overall forest ecosystem. That makes bats what scientists call indicator species.

The flying mammals respond and adapt to even small changes in their environment. Bats may alter their diets or behavior. Their populations may grow or shrink. “We can monitor the fruit-eating bats to see how the forests are changing. These particular bats might tell you something,” explains Lim.

When ecosystems lose biodiversity they aren’t as quick to recover from the stress brought on by, say, pollution.

Ecologists studying the relationships within ecosystems have found that species living in polluted environments do better when they include a greater variety of organisms. That is why the loss of even a single species can trigger a cascade of changes. Scientists are already seeing that happen with bats in some rainforests, including some in Mexico. There, scientists have found fewer species of bats in tropical areas where deforestation — tree cutting — has left holes in the forest canopy.

Fewer trees leave bats with fewer places to roost and less food to eat. In response, bats will tend to move elsewhere or die. And without enough bats to pollinate flowers or to spread seeds, the rainforest could start to lose plant species.

Once Lim has cataloged the fanged leaf-nosed bat, he releases it unharmed to fly back off into the darkness. It is a process Lim has done over and over here deep in the Iwokrama Forest. “We’ve been going back to the same sites. It will be a few years down the road until we start seeing trends and whether things are changing,” say Lim. He then grabs his gear and plunges back into the rainforest. It’s time for the Bat Man to recheck his nets. It’s a task he carries out almost hourly — from dusk until midnight — every night that he’s here.

Project Guyana – Operation Wallacea and Royal Ontario Museum from Joshua J. See on Vimeo.

Power Words

biodiversity The number and variety of organisms found within a geographic region.

caiman Four-legged reptile related to the alligator that lives along rivers, streams and lakes in Central and South America.

canopy The top layer of a forest, where the branches of the tallest trees overlap.

development The conversion of land from its natural state into another so that it can be used for housing, agriculture, or resource development.

DNA A long, spiral-shaped molecule that carries genetic information. It can be found inside nearly every cell of an organism.

ecosystem A group of interacting living organisms — including microorganisms, plants and animals — and their physical environment within a particular climate. Examples include tropical reefs, rainforests, alpine meadows and polar tundra.

herpetologist A scientist who studies the biology of reptiles and amphibians.

mist net Fine mesh net used by biologists to capture unharmed birds and bats for research.

rainforest Dense forest rich in biodiversity found in tropical areas with consistent heavy rainfall.

sequencing Technologies that determine the order of nucleotides or letters in a DNA molecule that spell out an organism’s traits.

species A group of similar organisms capable of interbreeding.

stress A factor, such as unusual temperatures, moisture or pollution, that affects the health of a species or ecosystem.

tapir A large, nocturnal, plant-eating mammal that is shaped like a pig and closely related to horses and rhinos.

transect Path followed by biologists to record animals or plants of interest.

understory Plants that grow beneath the canopy, or uppermost level, of the forest.

zoologist A scientist who studies animals and their habitats.

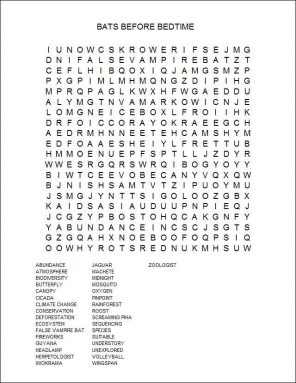

Word Find (click puzzle image below for larger version to print)