Nature’s coast guards

Barrier islands aren’t just for beach vacations — they protect coasts from storms and flooding

This satellite image from Sept. 17, 2005, shows Horn and Petit Bois — two thin, snakelike barrier islands protecting part of the U.S. Gulf coast (which appears red in upper part of photo). Almost three weeks earlier, Hurricane Katrina savaged both islands. It eroded parts of their ends, which now lie below water.

NASA

Many long, thin offshore ribbons of sandy dry land hug coasts along the Gulf of Mexico and mid-Atlantic United States. Called barrier islands, these spits of land run parallel to the coast, like walls.

The United States has more than 400 barrier islands. That’s the most of any country. More than 1.4 million Americans live on barrier islands. Millions more visit them, especially in summer. Some barrier islands are famous for their vacation resorts, such as Fire Island in New York; Long Beach Island in New Jersey; North Carolina’s Outer Banks; Sanibel and Captiva islands in Florida; and South Padre Island in Texas. Other barrier islands have gained renown as parks and nature reserves that protect wildlife.

But the biggest value that barrier islands offer is their ability to shield coastlines from the punishing force of ocean storms.

Wind, waves and currents form and erode barrier islands. Although these islands can last for thousands of years, many today face serious threats. Key to their survival is the ability of these islands to shift and move in response to wind and waves. But when people cover barrier islands with roads, parking lots and buildings, they block the natural flow of sand. And that makes these islands erode more easily.

Meanwhile, changes to the flow of onshore rivers have cut off the supply of sediments that replenish barrier islands. With global warming, sea levels have been rising. This means that with every wave, more water washes onto barrier islands. Scientists have also linked rising global temperatures to more and stronger ocean storms. So winds and waves strike the islands with more force, causing more damage.

Fortunately, there are steps communities can take to make barrier islands stronger — and the mainland safer. And as scientists learn more about how barrier islands grow and change, they are finding that sometimes these islands can even heal themselves.

Shape shifters

Unlike a brick wall that stands rigidly in place, barrier islands constantly morph. Ocean currents move sand along the shoreline. Those currents wear down the beach in some areas, building it in others.

“Waves are strong in winter, so they wash sand off of beaches and it piles up underwater,” says Hilary Stockdon. She studies coastal change for the U.S. Geological Survey in St. Petersburg, Fla. (This agency’s scientists study Earth, its resources and natural hazards.) “In summer,” Stockdon says, “gentler waves push sand back onto the shore, so the beach grows.”

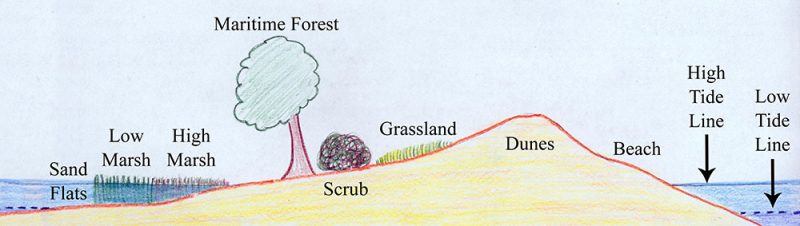

If you landed on a barrier island from the side facing the open ocean, you would come ashore on a flat beach. Moving by foot toward the mainland, you would climb over sand dunes. Next you might pass through dense thickets of hardy trees and shrubs at the island’s center. Emerging on the other side, you would slosh through salt marshes, then wade or swim across a bay (sometimes called a sound) to the mainland.

These different zones provide homes to many types of wildlife. Seabirds scurry along beaches, plucking treats from the wet sand, including clams and other mollusks. Rabbits and deer browse in the islands’ underbrush. Crabs, shrimp and fish spawn in the marshes, which protect the sea creatures’ young from ocean surf. Once a year, sea turtles may crawl ashore to lay their eggs.

The biggest changes to barrier islands occur during strong storms. When large waves and stiff winds lash ocean-side beaches, they transport sand up over the dunes and down into marshes on the far side. While the beach erodes, the other side of the island grows. As this process repeats over centuries, the island eventually rolls over itself, moving slowly toward the mainland.

One island, two directions

The changes a barrier island undergoes can provide a glimpse of geologic forces in action. For instance, photos of one of these islands — Assateague (ASS ah teeg) — show how they can actually change location.

Assateague lies off the coast of Maryland and Virginia. It is famous for its herds of free-roaming wild horses. (Misty of Chincoteague, an award-winning book published in 1947, was inspired by a real pony raised on a small Virginia island next to Assateague.)

Sixty kilometers (37 miles) long, Assateague used to stretch 16 kilometers farther north. A 1933 hurricane changed that. The storm sent ashore waves so powerful that they cut a channel, or breach, straight across the island. The breach cut off Ocean City, Md. — already a popular beach resort — from the rest of Assateague. Today, it’s hard to believe Assateague and Ocean City ever were connected.

State and federal agencies now protect Assateague as a wild seashore. It has campgrounds, but no stores or restaurants, and few roads. Meanwhile, Ocean City is a bustling vacation town, with high-rise hotels and shopping centers. Pavement covers nearly everything but its beaches.

Photographs taken from the air reveal how Assateague and Ocean City have gone their separate ways. Assateague has gradually shifted westward, toward the mainland, as storms have rolled over it. “Someday Assateague will merge into the mainland,” says Kelly Taylor. She is a science educator for the National Park Service. But that won’t be for a long time, Taylor adds. Meanwhile, the park “is home for lots of animals and birds now. They can live there as the island moves, because it shifts very slowly.”

North of Assateague, in Ocean City, acres of concrete and asphalt anchor the island in place. Of course, storms roll over it too. Each washes some sand from the beaches onto the streets. City crews clear away that sand, so it won’t block traffic — or fill in any marshland. That means the island can’t roll over, as Assateague does. Without new sand, Ocean City should be shrinking.

The Army Corps of Engineers (a government agency that manages big construction projects) works hard to keep that from happening. The Corps brings in special boats that carry powerful pumps. The pumps vacuum sand from the ocean bottom and then spew it onto the shore. There, bulldozers shape the sand into new dunes. This work is called beach replenishment. In Ocean City, it happens at least every four years, or more frequently after big storms.

In 2012, Hurricane Sandy badly eroded Ocean City’s beaches and dunes. The town now plans big repairs. To reverse effects of the storm, engineers will dredge up 765,000 cubic meters (1 million cubic yards) of sand. That’s enough to fill more than 300 Olympic-size swimming pools. The work will cost between $10 million and $25 million.

Local officials think this work is a good use of the money. After all, they argue, tourists won’t visit damaged beaches. Experts point out, however, that storms inevitably reshape barrier islands. And at some point, it just won’t make sense to keep rebuilding beaches that suffer heavy and repeated storm damage.

“Restoring beaches is a temporary solution. If communities decide to manage erosion that way, they will be doing it forever,” says Robert Young. A geologist at Western Carolina University in Cullowhee, N.C., he’s an expert on coastlines.

Making smart fixes

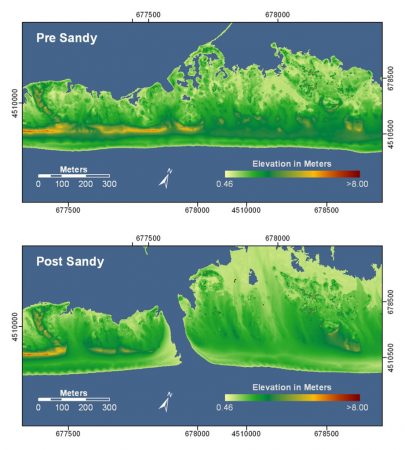

Since Hurricane Sandy, many scientists have worked to gauge the damage it caused to the U.S. East Coast. Some researchers used a laser-based tool called LIDAR (LY dahr), short for light detection and ranging. From a plane, the scientists repeatedly bounced a pulse of laser light off the ground. LIDAR measured how long (and how far) each laser pulse traveled. Those measurements helped map storm-related changes to the shape of islands.

Thanks to good planning, some scientists mapped different East Coast barrier islands with LIDAR one or two days before Sandy struck. The experts rushed in just as people who lived on the islands were rushing out to safety. Scientists came back with LIDAR again right after the storm.

Comparing their detailed before-and-after measurements reveals how much erosion Sandy caused to whole islands, as well as to individual beaches. On some parts of New York’s Fire Island, for example, Sandy eroded more than 3 meters of sand off of the top of ocean beaches and dunes. LIDAR images show that the storm piled up this sand near the center and shoreline on the mainland side of the island.

Combining these observations with computer programs, scientists now can better predict how future storms may affect barrier islands. Those studies will help government agencies decide when and where to restore beaches and dunes after storms hit. “We can’t protect everything,” says Young. “We don’t have enough money, and there isn’t enough sand.”

For example, Hurricane Sandy created two breaches in New York’s Fire Island. This barrier island is partly developed and partly protected as a national seashore. Engineers closed one of the gaps to protect mainland communities behind Fire Island from flooding. But they are watching the second breach. It lies in a wilderness zone and might close by itself. Young and other coastal scientists believe breaches can make barrier islands stronger by allowing currents to carry sand to their inland sides. There, the sand helps build up marshes.

Some islands go ‘hungry’

On some other barrier islands, there simply isn’t enough sand to go around. In the Gulf of Mexico, rising seas and heavy storms are eroding barrier islands off the coast of Louisiana. There isn’t enough sediment flowing through coastal marshes to replenish the islands. And that’s because people have built huge walls, called levees, to contain the Mississippi River.

The Mississippi spills into the Gulf of Mexico. Each year, the river carries hundreds of millions of tons of sediment down from Midwest farmlands. For centuries, the river would often overflow its banks, washing sediment into Louisiana marshes. Because those floods threatened towns, engineers built levees to hold back the river. But those levees also channel the river’s load of sediment far offshore into the Gulf of Mexico. As a result, Louisiana’s marshes and barrier islands are being starved of the sediment they need to rebuild.

Louisiana’s barrier islands don’t just protect its coast from storms. They also provide important nesting and breeding spots for many types of fish and birds. They are so important that the state is using $320 million from the oil company BP — money paid to help repair damages from a huge oil spill in 2010 — to restore four barrier islands. Engineers will rebuild beaches and dunes on the islands and build up their marshes.

That’s a lot of money for four islands. However, healthy barrier islands are a good investment, experts say. Without barrier islands to absorb the force of storms, many cities and towns along the Atlantic and Gulf coasts would be in much greater danger from winds, waves and flooding during storms.

“Places like Assateague, the Outer Banks, and Padre Island are lines of defense,” says Katie Arkema in Palo Alto, Calif. This Stanford University researcher studies the benefits provided by barrier islands and other coastal ecosystems, such as marshes and coral reefs.

As one example, Hurricane Sandy covered parts of Fire Island in New York with as much as 1.7 meters (5.6 feet) of water. Because Fire Island soaked up a lot of floodwater, communities behind it on the mainland were flooded by only around 1 meter. That still caused a lot of harm, but the reduced flooding probably saved some houses from being severely damaged.

Barrier islands provide protection against storms, beautiful places to visit and homes for fish, birds and other animals. As scientists learn more about how barrier islands actively form and change, people can take steps that will ensure these islands continue to play those roles for centuries to come.

Power Words

barrier island A low, narrow, sandy island that develops just off the coast.

beach replenishment Bringing in new sand to build up beaches and dunes damaged by storms.

develop (as with towns) The conversion of wildland to host communities of people. This development can include the building of roads, homes, stores, schools and more. Usually, trees and grasslands are cut down and replaced with structures or landscaped yards and parks.

dredge To remove sand and sediment from the ocean floor.

erosion To wear a surface away, usually with the force of wind or water.

geology The science that deals with Earth’s physical structure and substance, its history and the processes that act on the planet.

global warming An increase in the average temperature of Earth’s atmosphere, especially a sustained increase great enough to cause changes in the global climate. Many scientists believe that Earth has been in a period of global warming for the past half-century or more, due in part to the increased production of greenhouses gases related to human activity.

LIDAR (an abbreviation for light detection and ranging) A tool to measure the shape and contour of the ground from the air. It bounces a laser pulse off a target, and then measures the time (and distance) each pulse traveled. The measurements reveal the relative heights of features on the ground struck by the laser pulses.

marsh A low-lying wetland usually covered with grasses and shrubs, not trees. It’s a prime feeding and nesting ground for waterfowl.

sediment Matter that settles to the bottom of a liquid. Examples include sand or silt on the ocean floor.

wetland A low-lying area of land either soaked or covered with water. It hosts plants and animals adapted to live in, on or near water.