To protect kids, get the lead out!

The brain impacts of low levels of lead — from peeling paint and other sources — can be seen within large groups of kids

Peeling paint on a window and its sill. Old, peeling paint is a major source of the lead that children can encounter.

© gwflash / iStockphoto

Lead is a toxic heavy metal. That’s why, about 40 years ago, U.S. companies were ordered to stop adding lead to paints and gasoline. Unfortunately, plenty of this toxic metal still pollutes the environment. Worse, it also is poisoning hundreds of thousands of American children. Now a study shows the steep price these kids can pay. Even a little bit of lead can seriously harm their performance on school tests.

Lead is especially toxic to the growing brain. Indeed, explains Anne Evens, “The brain’s development changes as a result of lead exposure.” An environmental health scientist, Evens co-authored the new study. Previously she headed the childhood lead-poisoning prevention program in Chicago, Ill.

In the new study, Evens and her colleagues looked at records for tens of thousands of Chicago students. The researchers found children in third grade who had even very low blood levels of lead did poorer on state math and reading tests.

Where did the lead come from?

Lead is everywhere. That is especially true in big cities and in neighborhoods with lots of old houses. Lead paint flakes off of walls. And lead that spewed decades ago in the exhaust of vehicles fueled with gasoline still taints soil and water.

As a result, children inhale dust containing lead. Kids also can swallow lead dust. Infants and toddlers in particular do this. One way these young children explore their world is through touch and taste. If the dust in their environment contains lead, the metal can go right from a child’s fingers into her mouth.

The development of the brain includes the growth of nerve cells, called neurons. The brain forms links among those neurons as it grows. And lots of that development takes place when children are infants and toddlers. Lead interferes with the process. So lead poisoning can have lasting effects on a child.

Digging through data

Evens and other experts in Illinois and British Columbia, Canada, examined one of those effects: whether lead poisoning worsened a child’s scores on school tests. The team linked — or matched up — data on more than 57,000 third-graders from Chicago’s public schools. These data included birth and school records, as well as results of blood tests.

The team wanted to scout for any signs of harm due to low levels of lead. Thus, the experts focused on children with blood-lead levels below 10 micrograms per deciliter. More than 47,000 children fell into this category.

The researchers then created a computer model. This computer program had a built-in tool to make sure the effect on scores was likely due only to lead. To do this, the model ruled out other factors that also could affect test scores. The model also showed how levels of lead in the blood correlated with higher chances for failure. This inverse correlation showed how an increase in lead levels was associated with lower test scores.

And even very low lead levels indeed seemed to exert some harm.

The U.S. government used to say that any blood-lead level in children below 30 micrograms per deciliter was acceptable. No longer. Over the years, far lower levels have been linked to harm in kids. Finally, in May 2012, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention announced that for children, no level of lead is safe. This U.S. health agency said its goal is now to keep levels in kids very low: below 5 micrograms per deciliter.

The results from Evens’ team show why that matters. Overall, the group linked each 5 microgram increase in blood lead levels with a 32 percent greater chance of failing both the reading and math parts of a state test given to third-graders. Environmental Health published the findings on April 7, 2015.

Why low lead levels are especially worrisome

The effects of lead were not the same at all levels. Rather, among those students with very low levels of lead in their blood, each extra microgram of lead correlated with a greater chance of failing. In other words, for students with even a little lead in their blood, every bit extra was linked to a greater chance of doing poorly on tests.

For example, among students with less than 2 micrograms of lead per deciliter of blood, only about 11 percent failed the reading test . At 6 micrograms, however, the failure rate was 15 percent — or roughly one in every seven children.

“It’s really at the lowest [lead] concentrations where you see the most dramatic effects,” notes Sheryl Magzamen at Colorado State University in Fort Collins. As an epidemiologist, she studies patterns of disease. She did not work on the new study.

Evens explains that her team’s study was strong because it looked at so many children at a single grade level. Their findings now show that lead poisoning doesn’t just hurt a few kids, here and there. Rather, the heavy metal harms large groups of children.

Recent research by Magzamen found a similar link between lead and test scores. Her study looked at fourth graders in two Wisconsin cities. “For kids that scored lower on the standardized tests, lead had a bigger effect on [those] scores,” Magzamen says. To put it another way, she says, “Kids that are struggling often are also the kids that have [had] the highest exposures to lead.” Her team’s study appeared in Environmental Research in February 2015.

The brain is “forming so many connections” when children are infants and toddlers, Magzamen explains. Any “environmental insult” can change the way the brain’s nerves grow and become wired together. (In medicine, an insult is an event or occurrence that causes damage to an organism.) While lead is toxic, it also is persistent. Lead doesn’t go away. So its risk to health also lingers.

Now what?

Both Magzamen and Evens hope their studies will spark action. “I’d like to see greater investment in preventing lead exposure,” particularly in cities, says Evens. “I think we owe it to our children.”

One step would be for cities to do more to remove lead. One place to start would be in areas with lots of lead paint. Contaminated soils would also need to be cleaned up.

“This problem doesn’t seem to be going away even 40 years after lead has been banned,” Magzamen says. “We really need to think about making sure our next generations are not exposed.”

Power Words

(for more about Power Words, click here)

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, or CDC An agency of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, CDC is charged with protecting public health and safety by working to control and prevent disease, injury and disabilities. It does this by investigating disease outbreaks, tracking exposures by Americans to infections and toxic chemicals, and regularly surveying diet and other habits among a representative cross-section of all Americans.

circulation (in biology) A term that refers to the pumping of blood through the arteries, and smaller types of vessels (and from there into other organs and tissues).

computer model A program that runs on a computer that creates a model, or simulation, of a real-world feature, phenomenon or event.

correlation (v. to correlate) A mutual relationship or connection between two variables. When there is a positive correlation, an increase in one variable is associated with an increase in the other. (For instance, scientists might correlate an increase in time spent watching TV with an increase in risk of obesity.) Where there is an inverse correlation, an increase in one value is associated with a decrease in the other. (Scientists might correlate an increase in TV watching with a decrease in time spent exercising each week.) A correlation between two variables does not necessarily mean one is causing the other.

data Facts and statistics collected together for analysis but not necessarily organized in a way that give them meaning. For digital information (the type stored by computers), those data typically are numbers stored in a binary code, portrayed as strings of zeros and ones.

deciliter One-tenth of a liter (equal to 3.4 fluid ounces or 6.7 tablespoons).

development (in biology) The growth of an organism from conception through adulthood, often undergoing changes in chemistry, size and sometimes even shape.

epidemiologist Like health detectives, these researchers figure out what causes a particular illness and how to limit its spread.

gram A measure of mass in the metric system. A kilogram (kg) equals 1,000 grams. A microgram (µg) is one thousandth of a gram.

lead A toxic heavy metal (abbreviated as Pb) that in the body moves to where calcium wants to go. The metal is particularly toxic to the brain, where in a child’s developing brain it can permanently impair IQ (a test score that aims to measure intelligence)even at relatively low levels.

micro A prefix for fractional units of measurement, here referring to millionths in the international metric system.

model A simulation of a real-world event (usually using a computer) that has been developed to predict one or more likely outcomes.

neuron or nerve cell Any of the impulse-conducting cells that make up the brain, spinal column and nervous system. These specialized cells transmit information to other neurons in the form of electrical signals.

statistics The practice or science of collecting and analyzing numerical data in large quantities and interpreting their meaning. Much of this work involves reducing errors that might be attributable to random variation. A professional who works in this field is called a statistician.

toxic Poisonous or able to harm or kill cells, tissues or whole organisms. The measure of risk posed by such a poison is its toxicity.

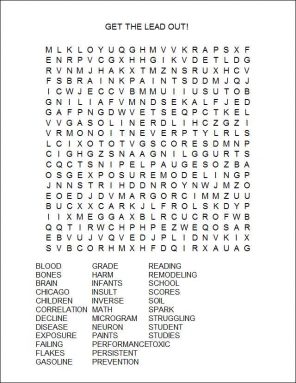

Word Find (click here to enlarge for printing)