A major science fair set these scientists on the path to STEM success

Competing at the International Science and Engineering Fair is its own reward, alumni say

The annual International Science and Engineering Fair draws competitors from all over the world. Some have gone on to win Nobel Prizes and other scientific honors.

Chris Ayers Photography/Society for Science

Today, teens from around the globe claimed big prizes at the 2022 Regeneron International Science and Engineering Fair. The competition, known as ISEF for short, is an annual event hosted by the Society for Science (which also publishes Science News for Students). More than 1,700 high schoolers gathered online and in Atlanta, Ga., this week to vie for nearly $8 million in scholarships and other awards. Top winners were honored for projects such as a new and improved motor for electric vehicles and a new material to make and store hydrogen fuel. (See box below.)

This year’s ISEF winners — and indeed, all ISEF competitors — join the ranks of thousands of alumni who have competed in the science fair since 1950. Some of those alumni have gone on to win Nobel Prizes or other scientific honors. Others have founded nonprofits, directed documentaries or written books. And many look back on ISEF as a formative experience.

To get a bit of insight into that experience, Science News for Students sat down with three scientists who competed in ISEF as teens. All three have gone on to win MacArthur “Genius Grants.” Here’s what they had to say about the world’s premier high-school science fair and how it impacted their lives.

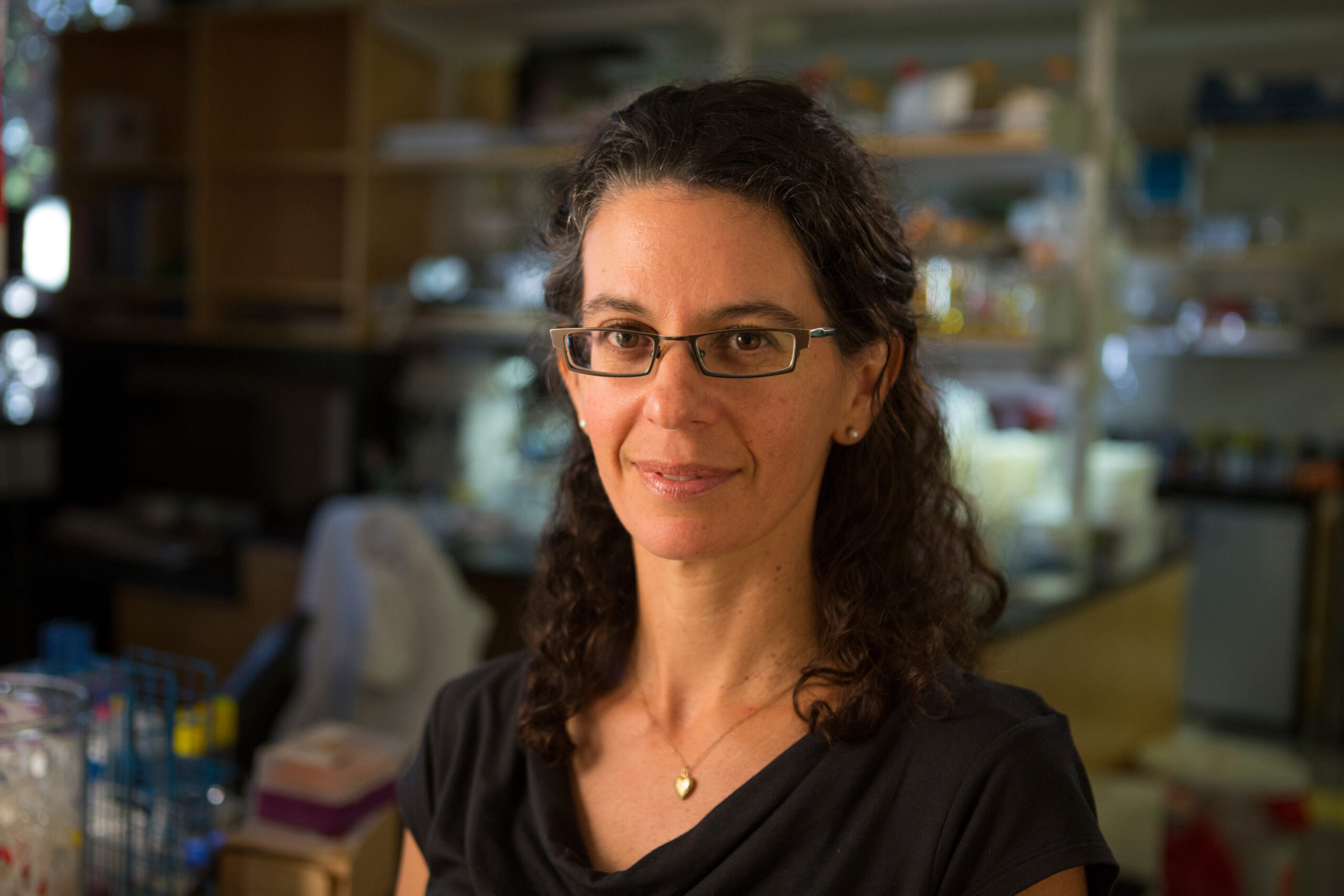

Dianne Newman

Newman competed in ISEF in 1987 and 1988. Her physics projects examined vibrations in different rigid materials. She is now a microbiologist at the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena.

How would you describe ISEF?

“A totally formative experience that changed my life,” Newman says. “It gave me a taste of how much fun research can be, and how much joy there is to be able to share your research with others.” She adds, “Being able to talk to judges and be taken seriously as a young person about the science I was doing was very inspiring … and helped me realize that a scientific career might be one that I could succeed at.”

What was most memorable about ISEF?

Newman traveled to ISEF with two directors of the Virginia state science fair, Nancy Aiello and Sally Wrenn. “By far the most memorable experiences I had were with them and becoming good friends with them,” Newman says. One night, for instance, Aiello dragged her mattress out onto the balcony to sleep. “In the middle of the night,” Newman recalls, laughing, “there was this incredible wind storm, and her mattress almost flew away.” Aiello and Wrenn would later attend Newman’s wedding — and she invited them to her induction into the National Academy of Sciences. “I really thank them for helping me launch as a young scientist,” she says.

Any advice for science fair newbies?

“Try to find a project that stimulates you. That you’re genuinely curious about. And then, push yourself to explore it as rigorously as you can,” Newman says. “It’s a wonderful process to feel like you’re becoming a little bit of an expert in some small piece of the scientific world. It’s very fulfilling, and you have a lot that you gain from that no matter what. It’s really the process of the investigative design and the creativity that comes with doing a project that is the big win.”

Raj Chetty

Chetty was an ISEF finalist in 1997. His project focused on methods to stain cells. Chetty did the work in a cell biology lab at the Medical College of Wisconsin in Milwaukee. Today, he’s an economist at Harvard University in Cambridge, Mass.

Any advice for getting involved in a research lab?

“It’s worth just reaching out to folks. I think lots of people want to help the next generation,” Chetty says. “If you’ve got an idea, if you’ve got a passion … try to contact people who might be able to help you. And don’t feel intimidated by, ‘How is anyone going to want to talk to me as a high-school student?’ I think if you reach out to enough folks, there are often people who are interested.”

How would you describe ISEF?

“An incredible opportunity to really showcase some work you’ve been passionate about, and meet lots of other high school students who are interested in science,” Chetty says. It’s also a sneak peek at the next generation of leading scientists and other change-makers, he adds. “I know many people who competed in ISEF at the same time as me,” he says, “who I see now in my professional career as professors at Harvard or leading scientists. … It’s kind of cool to see high-school students who you knew in a very different context being people who have really changed the world.”

How did ISEF impact your life?

“I pursued a career in social science, rather than the natural sciences,” Chetty says. “So, part of what I figured out is that I was very interested in science, but maybe more interested in the mathematical and statistical aspects of what I was doing than the biological aspects.” His experience doing biology research has shaped the way he thinks about social science, too. “I would say, at a broader level, my approach to social science is to make it more scientific, in a way,” he says. To Chetty, that has meant building an economics lab modeled after scientific laboratories — with many people working on empirical research together. “I would trace the roots of some of that back to the experience I had working on that ISEF project and having the experience in a lab environment,” he says.

Kelly Benoit-Bird

For her 1994 ISEF project, Benoit-Bird studied sounds produced by bottlenose dolphins. She did the research while working at an aquarium near her home in Connecticut. Today, Benoit-Bird still studies marine biology through sound at the Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute. That’s in Moss Landing, Calif.

What challenges did you face in doing your project?

“I didn’t come from a family background that understood research opportunities at all,” Benoit-Bird says. “I was the first person in my family to go to college.” When she started studying dolphins for fun, Benoit-Bird didn’t even know that ISEF existed. “There was no internet back then! You couldn’t Google these things,” she says. “I was so fortunate to have some really strong mentors in my high-school biology and physics instructors.” When it comes to finding mentors, Benoit-Bird says, “following your curiosity is really the best advice. … I think people in general are really excited to support students when they are following their passions.”

What was most memorable about ISEF?

“Just meeting people from all over the country and all over the world,” Benoit-Bird says. At ISEF, students get to know each other through icebreaker activities such as a pin exchange, where people swap pins that represent their cities, countries or cultures. “I’m not, by nature, an extrovert,” Benoit-Bird says. But doing those icebreakers “makes it a lot easier to put yourself out there and get a chance to meet people.” Since Benoit-Bird knew where she would be attending college in the fall, she also got to meet some of her future classmates. “It helped make that transition a little bit less scary,” she says.

Any advice for science fair newbies?

“Follow something that you’re passionate about. Don’t put too much emphasis on how it will be judged,” says Benoit-Bird, who has judged the Hawaii state science fair. “As a judge, I want to see your passion for your project.” Benoit-Bird remembers how nerve-wracking it can be to face the judges. But she says not to stress about it. “They’re not asking you questions because they want to trip you up. They’re there to ask you questions because they really want to know the answers,” she says. “They want to know what you found. They want to know why you’re excited about it.”

Editor’s note: Dianne Newman serves on the board of trustees for the Society for Science, which publishes Science News for Students.

2022 winners at Regeneron ISEF

High school students from around the world took home awards at the 2022 Regeneron ISEF. The hybrid event brought 1,181 finalists to Atlanta, Ga., this week, and another 569 online. Roughly 600 of these finalists shared nearly $8 million in prizes. The top award of $75,000 went to a Florida teen from Fort Pierce Central High School. He won the George D. Yancopoulos Innovator Award (named for Regeneron’s cofounder).

Magnets in the motors of today’s electric vehicles use rare-earth minerals, which are harmful to harvest. Robert Sansone, 17, thought another type of motor, which doesn’t use the minerals, might work too. But this “synchronous reluctance” motor hasn’t been very powerful. Recalls Robert, “I’m thinking, how can we improve this design” for use in electric vehicles? His winning prototype, which he estimates took at least 1,000 hours of work, went through 15 versions. “It got really difficult at times,” he says. But this new design, he feels, “opens up all new doors for the machine.”

Rishab Jain, 17, of Westview High School in Portland, Ore., and Abdullah Al-Ghamdi, 17, of Al-Hussan High School in Dammam, Saudi Arabia, each took home a $50,000 Regeneron Young Scientist Award. Rishab’s project used artificial intelligence to manipulate the genes in E. coli bacteria. This improved, he says, on a common technique for making medicines and vaccines. Abdullah Al-Ghamdi, 17, developed a type of metal-organic framework — or MOF — to help lower the cost of hydrogen fuels. A trio of students at Prince Royal’s College in Chiang Mai, Thailand shared the $50,000 Gordon E. Moore Award. Napassorn Litchiowong, 17, Chris Tidtijumreonpon, 16, and Wattanapong Uttayota, 17, created an app. It can identify sooner a type of infection that often leads to bile-duct cancer. This disease is a leading cause of death in their country, the teens report.

Other students were awarded trips to prestigious science events. Dozens of other organizations doled out special awards that included college scholarships. Each of the fair’s 21 categories also handed out four grand awards. — Anna Gibbs