Abdominal fuzz makes bee bodies super slippery

Tiny hairs act like a lubricant to protect shell-like parts that rub all day long

As a honeybee bends its abdomen, segments slide over each other like pieces of a telescope.

Susan Walker/Moment/Getty Images Plus

The summer buzz of honeybees means the sweet reward of honey. But to make enough of this sweet stuff for the hive, bees are in near-constant motion. As they move, overlapping sections of their tough outer skeleton, known as a cuticle (KEW-tih-kul), slide past each other. A study now finds that tiny hairs on that cuticle act as a lubricant. That fuzz reduces friction, which makes it easier for the bees to move.

Researchers could take a lesson or two from those bees, says Jieliang Zhao. He’s a mechanical engineer at Beijing Institute of Technology in China. What his team has just learned could lead to new ways to reduce wear and tear in materials. “For example,” he envisions adding bee-like fuzz to “the sliding edges on the handle of a folding umbrella,” This, he says, should keep the umbrella working smoothly for a longer time.

Honeybees evolved this fuzzy solution to friction, Zhao suspects, to cope with the fact that their bodies are always squirming. Even when a bee perches on a flower to feed or pauses to take a rest, its body is moving. Its head turns. Its legs sweep pollen and debris onto or away from the body. All the while, its abdomen is pulsing as it breathes. It’s this last part of the body that grabbed Zhao’s attention. He and his team wanted to learn how the hard shell-like external skeleton shielding honeybee abdomens could move so much, yet suffer so little damage.

To find out, the researchers recorded video. It showed different segments of the cuticle slide past each other as bee abdomens bend.

Hairy benefits

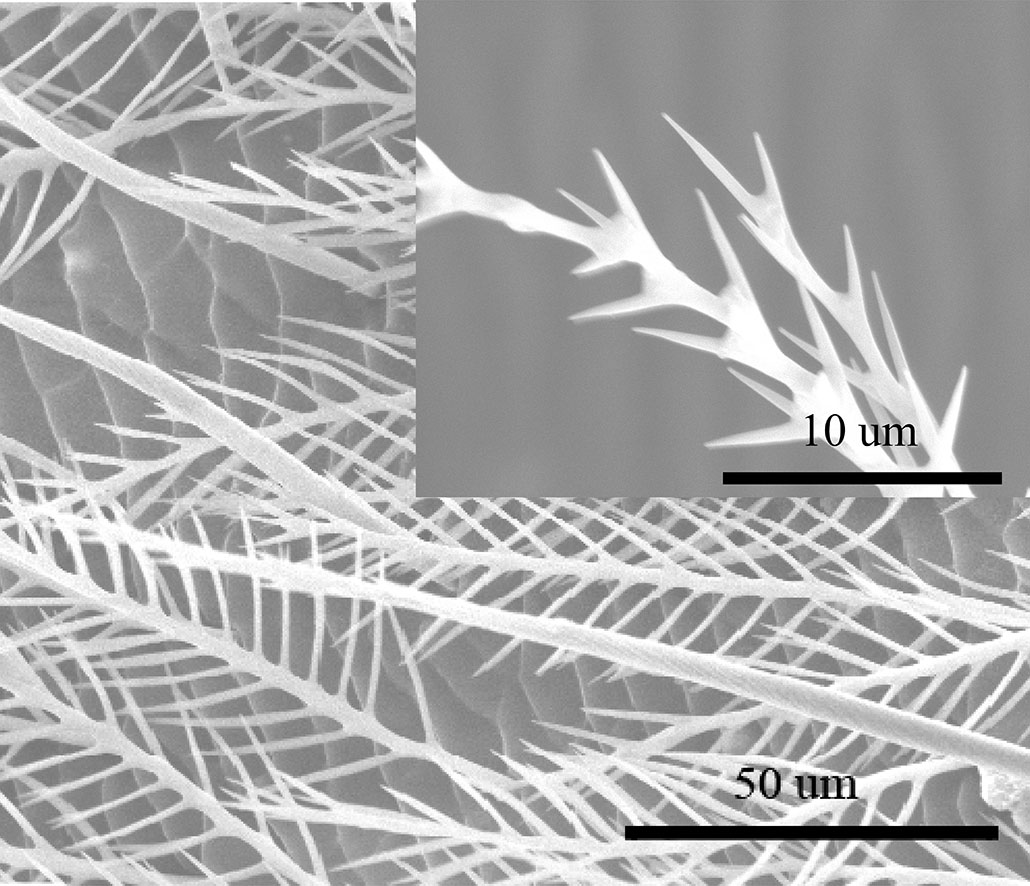

Next, Zhao’s group removed and cleaned the abdomens of bees that had died naturally. Then the researchers examined them using scanning electron microscopy. Some segments of cuticle were covered with tiny hairs. Each hair was very tiny — just 100 to 200 micrometers long. That’s about the same length as the width of two human hairs placed side-by-side.

Each hair in this fuzz is also branched. Dozens of tiny projections jut out from either side of a central shaft. The tip of each one is shaped like a tiny cone. The team wondered if the hairs’ unusual shape might reduce friction when pieces of the cuticle slide against each other.

To find out, the researchers cut out pieces of fuzz-covered cuticle. It came from a part of the abdomen that slides under a neighboring, bald piece. Zhao’s team cut out two pieces of that bald cuticle from elsewhere on the abdomen and connected one of them to an atomic force microscope. This tool allowed the team to measure friction as that piece slid over the other two.

The tiny hairs reduced friction, they found. And by a lot — up to 40 percent, compared to the smooth piece. “Forked hairs can improve the smoothness of the contact area,” Zhao now concludes.

As the cuticle moves across the hairs, energy builds up within the hairs. This makes it easier for the bee to move the segments, he says. There is also “less pressure with the object being touched,” Zhao explains. All of these features help cut friction between parts of the cuticle that rub against each other.

The Beijing team described its findings in the June 2 ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces.

“Mother Nature has developed many processes that are much more efficient than what we as people have invented,” says Neil Canter. He’s a chemist at Chemical Solutions in Willow Grove, Penn. Honeybee hairs are a good example, he adds. Friction ups the energy used in a process. Cutting friction, then, will lead to energy savings and sustainability, he points out.

There are many delicate structures in animals that could inspire our engineering designs, Zhao says. He and other materials scientists find the living world a source of inspiration. Turns out the buzz about bees may become about far more than just honey.