Alzheimer’s protein can sneak into the brain from the blood

Amyloid-beta proteins form sticky clumps in diseased brains, but may not start out there

People with Alzheimer’s disease show physical changes to their brains. One of them is the buildup of clumps of a protein called amyloid-beta. In this image of a mouse brain, the protein clumps are red and brain cells are green.

Strittmatter Laboratory/Yale University

One hallmark of Alzheimer’s disease is clumps of a misbehaving protein in the brain. But some of that protein might not have started in the brain. Experiments on mice now show that Alzheimer’s proteins can build up in the brain after sneaking in from the blood.

Alzheimer’s is an incurable disease. It usually strikes in old age and causes symptoms such as confusion and memory loss. Researchers aren’t sure exactly what causes the brain disease. But they know that the brains of affected people have sticky protein clumps, called plaques (PLAKS). The protein that forms these clumps is known as amyloid-beta (A-beta).

The new results suggest A-beta that forms outside the brain may play some role to Alzheimer’s disease, says Mathias Jucker. He’s a neurobiologist at the University of Tübingen in Germany who did not take part in the tests. Treating a person’s brain is difficult. But this finding may help scientists develop new treatments that target easier-to-reach parts of the body — perhaps including the bloodstream.

Extreme blood sharing

To be sure, cells in the brain make A-beta. But blood platelets, skin cells, muscles and other body parts do too. These other sites make it in small amounts. Researchers wondered whether, over time, blood might carry A-beta from those other sites into the brain, where it could collect.

Earlier studies in animals showed that A-beta injected into the bloodstream can enter the brain. But scientists didn’t know whether enough of this A-beta gets to the brain to do damage.

To test this idea, an international team of researchers performed tests using a form of extreme blood sharing. They used six pairs of mice. Each pair had one normal mouse. The second animal was a mutant. It carried some altered gene to make lots of human A-beta protein. Researchers surgically joined the mice so that blood flowed between those in each pair. And they continued to share each other’s blood for a year.

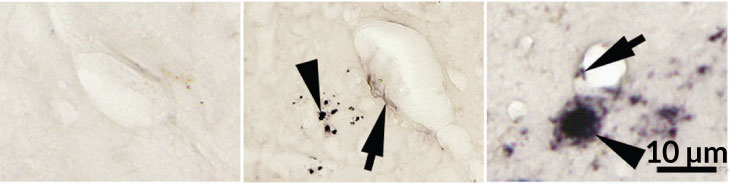

Afterward, brains of the mutant mice were full of A-beta plaques. That’s what researchers expected. But they also found plaques inside the brains of the normal mice in each joined pair.

Story continues below image.

The normal mice didn’t have as much A-beta in their brains. Still, the fact that they had any plaques was notable, says Weihong Song. He’s a neuroscientist in Canada at the University of British Columbia in Vancouver. He was also part of the group that conducted the experiments.

Other mice had no mutation and shared no blood with others. These control mice served as comparisons, showing what normal healthy mice should look like. And they had no protein clumps in their brains.

Song’s team published its findings online October 31 in Molecular Psychiatry.

Brains of the joined mice showed other signs of damage. The researchers saw inflammation and tiny areas of bleeding in the brains of normal mice that had shared blood containing lots of A-beta. The brains of these mice also contained a dangerous type of a protein known as tau. Both A-beta plaques and tangles of tau protein show up in the brains of people with Alzheimer’s disease.

Out of balance

The new results don’t mean that protein hitchhikers in blood cause Alzheimer’s disease. “We still think of Alzheimer’s as a brain disorder,” Song says. But in some cases, factors in the blood might nudge the disease along.

Normally, “there is a balance between A-beta inside and outside the brain,” he says. But this balance can be thrown off. The body may be chock-full of the protein. Or the blood-brain barrier — the blockade that keeps potential hazards out of the brain — may weaken with age. In any of these cases, the brain may get an extra dose, Song thinks. It’s possible that drugs, or treatments that reduce A-beta in the body, could tweak this balance in the right direction. And that might help slow or prevent Alzheimer’s disease.

The experiments don’t suggest that people can get Alzheimer’s from another person’s blood says John Collinge. He’s a neurologist at University College London, in England. “There really isn’t any evidence that you can transmit Alzheimer’s disease by blood transfusion,” he says. So this study is informative, he says, “but shouldn’t cause alarm.”