America’s duck lands: These ‘potholes’ are under threat

Scientists study important U.S. grasslands to learn what it will take to save their vital ecosystems

A mallard hen flies up from her nest, hidden in the prairie grass. Scientists will mark her nest so they can find it again.

Ryan Moehring/USFWS Mountain-Prairie/Flickr (CC-BY 2.0)

One morning last June, two scientists rode ATVs across the North Dakota prairie. They drove in parallel tracks. A long metal chain hung between the two vehicles. As they traveled, it bounced across the top of the knee-high grass. Suddenly, a startled bird took to the air as the chain passed overhead.

“Duck!” one scientist shouted.

Quickly, all hopped out of the four wheelers. They were on the run to check out the spot that bird had flown from. Buried in the grass, they found a nest holding 11 cream-colored eggs.

“These are blue-winged teal eggs,” noted Frank Rohwer. He’s a biologist with Delta Waterfowl. The organization is based in Bismark, N.D. Duck hunters set up the organization to conserve the habitat where ducks and other waterfowl live.

Blue-winged teals make their nests on the ground by weaving shallow baskets out of prairie grasses. The adults also pluck out some of their own down feathers. They use these soft feathers to insulate the nest. One of Rohwer’s tasks has been to calculate the share of duck nests with eggs that hatch each year. Such numbers help scientists better understand the overall health of ducks on the prairie. It also helps them monitor potential threats to these waterfowl. Some of those threats might include an increase in predators or the loss of good nesting habitat.

Each spring and summer, about half of all the ducks in North America — some 22 million birds — fly to a part of the Great Plains called the Prairie Pothole. It takes its name from the shallow ponds — a type of wetlands known as potholes — that checker these big swaths of wide-open grasslands. A large share of this area lies in North Dakota. Some people call it the “duck factory” of North America because of all the eggs that are laid here, and then hatch.

What makes these lands so important? In truth, from a car window, this prairie may not look like much. But it’s home to much that isn’t obvious from that car window.

Beneath its tall grasses, wildlife abounds. More than 300 species of birds and 200 species of butterflies live in this prairie. So do some 100 species of mammals.

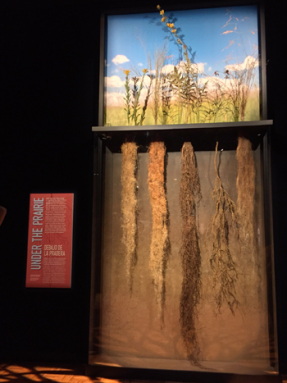

This prairie also provides many important services. Among these environmental services are its production of habitat to nurture all of that biodiversity (huge numbers of plants and animals). Prairie grasses keep wind from eroding the soils — scooping them up and letting them blow away. The region also stores important nutrients in its soils and plants. Underground, an extensive root system of prairie plants helps to filter pollutants when rainwater percolates through the soil.

“The prairie performs these important services. Yet there’s still so much we don’t understand [about it],” says Neil Shook. He manages the Chase Lake National Wildlife Refuge in central North Dakota.

Researchers who study prairie ecology are in a race against the clock. Why? Temperate grasslands are in trouble, including North Dakota’s prairies. Indeed, they are among the most endangered habitats in the world. Millions of acres of this land is plowed under each year for farming, or paved over as roads, or built upon for human use. In the U.S. Northern Great Plains alone — a five-state area consisting of North Dakota, South Dakota, Minnesota, Nebraska and Iowa, more than 5,200 square kilometers (2,000 square miles) of grasslands were cleared for corn and soybean crops between 2006 and 2011 alone. That’s an area a bit larger than the state of Rhode Island.

Shook, Rohwer and other scientists want to develop a more complete picture of how prairie plants and animals interact. That should help them and land managers better understand how people are changing the prairies and all of the life they host. This information, they say, is important to protecting those vital environmental services that prairies offer.

Story continues below image

The importance of prairie plants

“Plants are the base of a healthy ecosystem,” observes Shawn DeKeyser. He’s a plant scientist at North Dakota State University in Fargo. DeKeyser pries open the seedhead of a grasslike plant called a sedge. Its seeds are very small. To view them, he takes out a magnifying glass.

DeKeyser wants to see how the various grasses, wildflowers and sedges in native prairies compare to the plants found in grasslands that have been disturbed by farming. Native prairies, by comparison, are sites that have never been plowed for farming.

There are far fewer species of grasses and grasslike plants around prairie wetlands — those potholes — than in areas that were once farmed, DeKeyser found. The disturbed sites also tend to have more invasive species: weeds. These are plants not originally from the area. And they can cause problems. Disturbed areas tend to have fewer native species. DeKeyser says cattails are one example of an invasive species in prairie wetlands. Cattails crowd out many of the wildflowers and grasslike plants that typically would live in these places.

That spells trouble for the survival of animals — including insects — that evolved along with traditional prairie plants, explains Steve Chaplin. This is known as coevolution. It denotes two or more species that depend on each other for survival. Each undergoes changes in response to changes by the other.

Chaplin studies the Minnesota prairie. He works in Minneapolis, Minn., for a conservation group called the Nature Conservancy. He says the regal fritillary butterfly is one example of an insect that needs prairie plants to survive. It’s a big, showy orange-and-black butterfly. Its caterpillars eat only certain types of prairie violet flowers. The regal fritillary is now at risk of extinction due to the loss of those prairie flowers.

Yet scientists like Chaplin and DeKeyser are hopeful that some of these animal species will return.

DeKeyser experiments in an outdoor laboratory. He is testing different ways to put native prairie grasses back onto cropland that’s no longer in use. “If we can build back the plant diversity, we think the wildlife will [return],” he says.

Story continues below image

Spying on bees and birds

Clint Otto wears a white beekeeper’s suit inside an apiary. (An apiary is where people keep bee colonies.) This ecologist is collecting tiny, mustard-colored balls of pollen from a honeybee hive. Its residents gather pollen from flowers. The pollen sticks to hairs on their hind legs. Those hairs form little pollen baskets called corbiculae (Kor-BIK-yu-lay). The bees use these tiny baskets to haul pollen back to their hive.

Otto works at the U.S. Geological Survey’s Northern Prairie Wildlife Research Center in Jamestown, N.D. He’s taking pollen back to his laboratory where he will test it for plant DNA. This will give him clues to which flowers the bees had been visiting. That pollen came from bees living in a variety of habitats. He wants to probe how landscape changes have affected what the bees eat.

One in five honeybee colonies in the United States spend their summers in North Dakota. That’s some 250 million bees. Plentiful wildflowers and few people make the prairie here prime honeybee habitat, explains Otto.

No surprise, North Dakota also is the number one honey-producing state. Yet Otto worries that as more farmers convert prairies to crops such as corn and soybeans, it may become harder for bees to find a nutritious meal. “These agricultural crops provide limited resources for the bees,” he explains.

Like people, bees must eat a variety of foods to obtain ideal nutrition. Also like people, bees with a more nutritious diet tend to be healthier. And they make more honey, Otto notes. His work has turned up genetic material from 260 different plant species in the pollen collected from bees in just North Dakota.

“Our findings show how important [this diversity] is for bee health,” says Otto.

Story continues below image

There’s a lot that people have yet to learn about the behavior of bees and other prairie animals, says Kaylan Carrlson. She’s a wildlife scientist in Bismarck with Ducks Unlimited. It’s a national conservation group that focuses on protecting waterbirds and their habitat. Carrlson studies how ducks on the prairie interact with each other and their environment.

One reason scientists know so little about many prairie animals is that they can be hard to spot in the vast expanse of tall grasses, she explains. Carrlson is trying to change that. She supervised two college students who have spent their summers observing the goings on at duck nests on the prairie. The live video feed that they pored over came from tiny cameras hidden near those nests.

These students have been trying to learn about duck behavior. So far they’ve seen a blue-winged teal hen (a hen is a mother duck) fight off a badger. They watched another hen clean broken shells out of an empty nest after a fox ate her eggs.

“The data we collect from the nest cams can help us to better understand factors that lead to nest success and survival,” Carrlson explains. Scientists and decision-makers can use that information to better understand the pressures affecting ducks during their time on the prairie each year.

The goodness of grazers

Many animals that live on today’s prairie would have been familiar to Native Americans, the first humans to live on prairies. Yet there’s one large mammal that’s largely missing today: the American bison. Millions of these gigantic grass-eaters roamed North America’s prairie before people nearly hunted these majestic beasts to extinction in the 1800s.

“We didn’t know it at the time, but bison provided a really important service to the prairie ecosystem,” says Shook of the Chase Lake National Wildlife Refuge.

These buffalo ate a lot of grass as they crossed the landscape. It turns out that many prairie plants need this type of grazing to grow well. Without grazing, the grasses become overgrown. Each winter, old, overgrown grass gets mashed under snow. There it forms a thick mat. Layers of the previous year’s vegetation begin to stack up on the ground like blankets, notes Shook. In spring, these old layers make it hard for new grasses and plants to emerge. Buffalo once acted like natural lawnmowers for the prairie. They helped keep its grasses from becoming overgrown and stacking up.

But with few bison left, Shook’s team now gets the job done by relying on the buffalo’s closest common relative: the cow. Cattle eat plenty of grass. Ranchers mimic how herds of buffalo would have moved across the landscape. They control this by using a series of gates and fences. These channel cattle herds so that they move from one plot to the next across the Chase Lake refuge.

Shook also uses cows to mow areas now overrun with invasive plants. This gives native prairie species a chance to grow back. “My goal is to create the most biologically diverse ecosystem possible,” he says.

It seems to be working. He points to a pair of adjacent plots of land. Cattle have never grazed on one of them. Now overgrown, it contains just two types of grass and hosts very few animals. It’s dying.

The other plot is vibrant, colorful and noisy. It teems with dozens of different species of wildflowers. Insects and birds buzz and chirp. Cows graze here every year. It’s an example of a healthy and productive prairie.

Shook shakes his head in amazement. “Any time we can help to make an ecosystem healthier by increasing diversity,” he says, “that’s a win for me.”

Field reporting for this story was made possible by a fellowship from the Institute for Journalism & Natural Resources.