Among mice, scratching is catching — as in contagious

Scientists identify brain structures vital to this see-it, do-it behavior

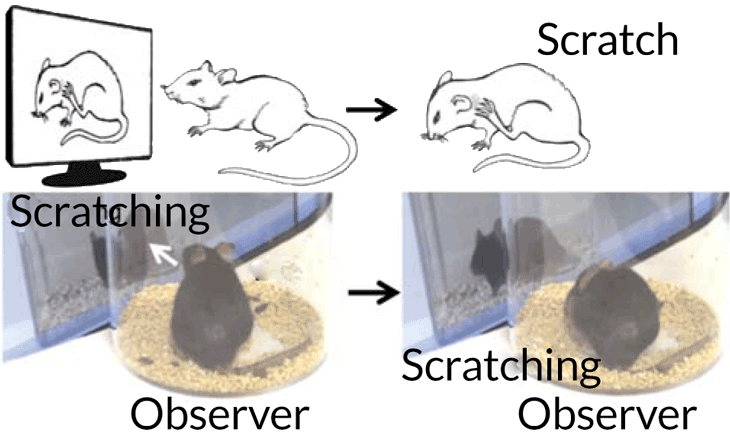

Like people, mice experience sudden itches after seeing other mice scratch. This is a boon for studying the neuroscience of contagious behaviors.

kozorog/iStockphoto

By Susan Milius

What happens when you see someone scratch a mosquito bite? You may start to feel an itch come out of nowhere. Then you might start to scratch, too. Mice, new data show, suffer the same strange phenomenon. It’s called contagious scratching.

Tests with mice provide the first clear evidence that contagious scratching can spread mouse-to-mouse, says Zhou-Feng Chen. As a neuroscientist, he studies the brain. He works at the Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis, Mo. His mice started scratching after watching an itchy neighbor. They even did this after just watching videos of scratching mice.

In discovering this, “there were lots of surprises,” Chen notes. One was that mice would even pay attention to some scratching neighbor. After all, mice are nocturnal. They mostly sniff and use their whiskers to feel their way through the dark. Yet Chen had his own irresistible itch to test the “crazy idea: that mice might share an urge to scratch, he says. And it paid off.

The quirk isn’t just a weird little finding, though. It opens new possibilities for exploring the basis in the brain for picking up such contagious behaviors.

Chen’s group described its new discoveries in the March 10 issue of Science.

How they did it

The researchers housed mice super-itchy mice within sight of some that didn’t scratch much. Then they recorded the animals on video. Shortly after a normal mouse looked at a neighbor scratching, it scratched, too. For a comparison, researchers gave others of these mice a not-very-itchy neighbor. These comparison mice also looked at their neighbor now and then. Rarely, however, would they scratch right after that glance.

And the neighbor didn’t have to be real. Sometimes it was just a mouse video. Animals that viewed the video of scratchers responded the same way. More audience itching and scratching followed the film of a mouse with itchy skin than one of a mouse just poking around on other rodent business.

Next, researchers looked for where contagious itching plays out in the animal’s nervous system.

Story continues below image.

Mice recently struck by contagious urges to scratch showed extra brain activity in several spots. These included, surprisingly, a pair of nerve cell clusters called the SCN, for suprachiasmatic nuclei (SU-per-ky-az-MAT-ik NU-klee-eye). These clusters are better known as the body’s internal clock. They keep they body’s daily — or circadian (Sur-KAY-dee-un) — rhythms on time. They respond to light. They use that daily signal to reset the clock so that it can keep the body’s internal activities in sync. (People have these SCN clusters, too. They’re found deep in the brain roughly behind the eyes.)

Other tests linked contagious itching with a small brain molecule nicknamed GRP. Scientists had known that GRP helps carry itch information elsewhere in a mouse’s nervous system. In the new tests, mice didn’t catch the urge to scratch if they had no genes to make this GRP or to make the molecule that detects it. Yet the mice still scratched when the researchers tickled their skin.

Also, in normal mice, injecting a dose of GRP into the SCN provoked scratching. And this was true even when there was no itchy neighbor in sight. Injecting salt water into the SCN did not set off much pawing. This seems to confirm that the brain’s clock can play a central role in triggering the scratch response — at least in mice.

How convincing are the new data?

Chen’s team has done fine work, says Gil Yosipovitch. He is a dermatologist, or skin specialist, in Florida where he directs the Miami Itch Center at the University of Miami. Still, he’s not sure how the mouse discovery might apply to people. So far, brain imaging in his own work has not turned up signs of a role for the SCN in contagious itching in people, he says.

Henning Holle is also puzzled by why the SCN alone might control behavior based on seeing a mouse scratch. Holle is a psychologist and neuroscientist at the University of Hull in England. Contagious scratching is “a very specific and rich visual stimulus,” he says. And research suggests other brain regions play a role in contagious itching in people, he says.

Tracking down how scratching spreads by sight is more than a science puzzle, Yosipovitch points out. Some people are troubled by strong, constant itching. These people can often catch the need to scratch very easily just by watching someone else scratch. And responding this way can make their own itching even worse. New ideas that come from studying these mice might provide clues to easing the misery that these people with a non-stop itch endure.