Analyze This: A good reason to drive with an adult in the car

Teens with new driver’s licenses take more risks than do those who are just learning to drive

Teens are eager to drive alone once they get their driver’s license. But it is much safer to keep driving with an adult.

lisafx/iStockphoto

For many teens, getting a driver’s license is an important milestone and a step toward independence. But having a license doesn’t ensure a teen will drive safely. Car accidents are the leading cause of teen deaths in the United States. And newly licensed teen drivers are twice as likely to have a fatal car crash per mile traveled as are teens who have been driving for a year or two. That’s according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

Here’s the good news. Teens who have learner permits and drive with an adult in the car seem to be fairly safe drivers. And even with a license, they tend to be safer drivers if there is an adult riding along. These findings come from a July study in the Journal of Adolescent Health.

In that new study, researchers outfitted 90 cars with sensors, cameras and GPS devices for at least 21 months. This allowed them to track and record drivers’ behaviors on the road. For the nine or so months that these teens had only a learner’s permit, they had to drive with a parent or adult guardian. During the year or so after the teens had gotten their licenses, they tended to drive solo. The researchers compared data from novice drivers or teens who had recently received a license to those from more experienced adult drivers.

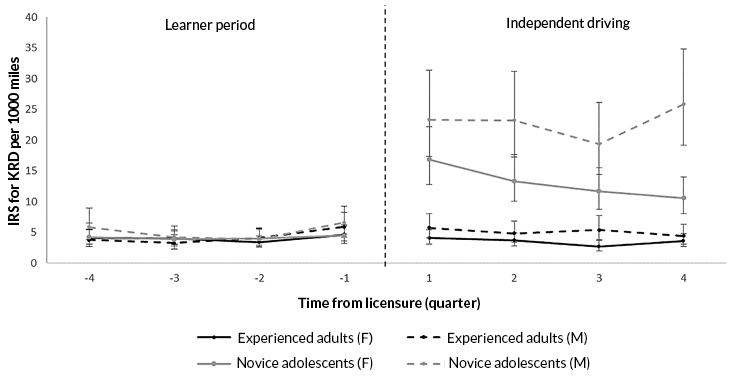

Scientists refer to one type of on-the-road events as KRDs. That’s short for kinematic (Kin-eh-MAT-ik) risky driving. This class of erratic behaviors affect a car’s motions. These include how many times drivers braked suddenly, how often they accelerated quickly or how many times they turned sharply per 1,600 kilometers (1,000 miles) traveled.

Such erratic behaviors make it harder for the driver to quickly respond to a sudden change in traffic. That might be an abrupt slow-down due to an accident up ahead. Or it could include a truck that suddenly swerves because of a flat tire. These KRD events also make it hard for adjacent drivers to predict what a vehicle will do. Researchers hope that finding ways for teen drivers to reduce KRDs might cut their risk of auto accidents.

Click here, or on the graph, for a larger image.

Data Dive:

- Compare the data for novice drivers (males and females) during the learner period (left) to independent driving.

- Which group saw the biggest increase in risky driving events?

- Which group saw the smallest change in risky driving events?

- Which group saw the biggest increase in risky driving events?

- These drivers were all volunteers from southwestern Virginia, a rural area near the Appalachian Mountains.

- How might the geography of where the volunteers drove affected their driving behaviors?

- How might the data vary in a more densely populated urban area? Why?

- Is it possible that volunteers might drive differently than other drivers? How? Do you think this would be a short or long-term effect?

- How might the geography of where the volunteers drove affected their driving behaviors?

- Was this graph difficult to understand? Why?

- What would improve this graph or make it easier to read? Explain.

Analyze This! explores science through data, graphs, visualizations and more. Have a comment or a suggestion for a future post? Send an email to sns@sciencenews.org.