Analyze This: Perfumes from everyday products collect in distant ice

These chemicals in ice at Europe’s tallest peak point to trends in human history

Fragrances show up in lots of soaps, shampoos and cleaners. The molecules that make pleasant scents can waft on the wind to remote places, such as Mount Elbrus, Europe’s highest point.

_curly_/iStock/Getty Images Plus

Perfumes don’t just come in fancy bottles — they also show up in plenty of boring, everyday items. Soapy suds for cleansing hands and bodies usually contain fragrances. So do the cleaners that keep homes spick-and-span. But those chemicals don’t always stay close to where they’re used. Now scientists are finding scent-bearing chemicals in ice at very remote places.

Over years, layers of unmelting snow become pressed into ice. Those layers trap dust and tiny bubbles of atmospheric gases. Ice cores are cylinders removed from such ice, such as a glacier. Such materials are like mini time capsules that contain clues to the past.

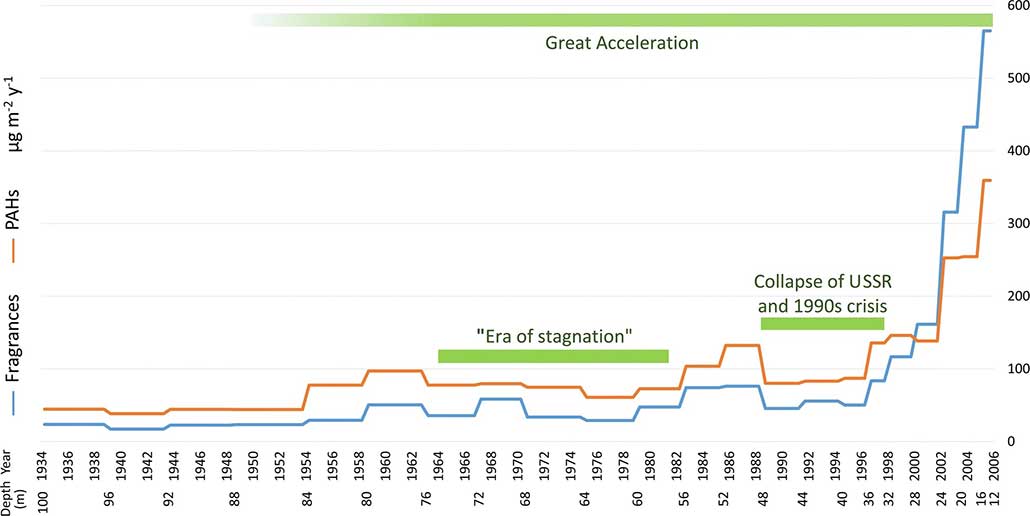

In a new study, scientists searched for traces of 17 perfumes in an ice core from Mount Elbrus in Russia. It’s Europe’s highest point. That core formed from snow that fell between 1934 and 2005. In the core’s most recent years, fragrances fell at a rate that was about 20 times higher than in the earliest years. The researchers shared their findings June 30 in Scientific Reports.

Mount Elbrus is very remote. But many people live in the surrounding region, notes Marco Vecchiato. He’s the study’s lead author. A chemist, he works at the Institute of Polar Sciences in Venice, Italy. The mountain lies in what was once the Soviet Union, also known as the USSR.

Vecchiato and his team found three molecules contributed most to the core’s collection of perfumes. Each has a fruity or floral scent. These chemicals cost little to make and often show up in soaps and shampoos. That may explain why they made up more than 80 percent of the perfumes in every ice sample, says Vecchiato. He says it shows that “everyday activities — just washing your hands and taking a shower — may have an impact” far from your bathroom.

The team also analyzed molecules called polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, or PAHs. Those tend to come from burning wood or fossil fuels, and from certain industries.

Trends in the perfumes and PAHs mirror the ups and downs of human activities near Mount Elbrus. The Soviet Union, for instance, experienced a time when its wealth grew relatively slowly. This period, between 1964 and 1982, is called the “era of stagnation” in the graph below. Rates of fragrance deposition dipped during this time. The Soviet Union then broke apart during 1989 to 1991. Again, the region struggled financially. Many people there lived in poverty. Some struggled to get enough food. Perfume levels in ice also took a tumble during that time. But by the 2000s, perfume use started to climb again.

Data Dive:

- Why do you think the lowest rates of perfumes falling on snow occur in the earliest years?

- How many times higher are the perfume levels in 2006 than in 1934?

- Look at the years marked “Era of Stagnation.” By about how much did perfume levels drop between 1960 and 1978?

- During the collapse of the Soviet Union, the amount of perfume used dropped. Estimate how much perfume levels dropped between 1986 and 1990. What might explain that drop?

- What might explain the steep rise in rates of ice accumulation of perfumes and PAHs in the 2000s?

- This ice core is from one place in Europe. Do you think other places in the world would show similar trends? Explain why or why not.