ape: A group of rather large “Old World” primates that lack a tail. They include the gorilla, chimpanzees, bonobos, orangutans and gibbons.

biologist: A scientist involved in the study of living things.

conservation biologist: A scientist who investigates ways to help preserve ecosystems and especially species that are in danger of extinction.

endangered: An adjective used to describe species at risk of going extinct.

factor: Something that plays a role in a particular condition or event; a contributor.

fickle: A term used to describe an attitude, opinion or loyalty that is changeable, often for no obvious reason, such as on a whim.

forest: An area of land covered mostly with trees and other woody plants.

frond: The large leaf (or leaf-like) part of a fern, palm or other plant whose edges have many parts to it, sometimes known as leaflets.

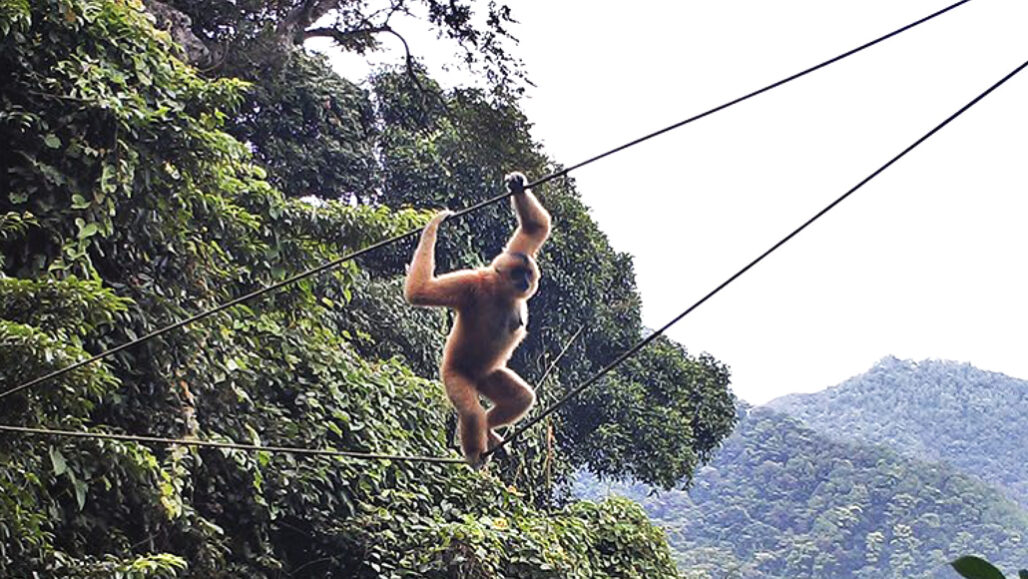

gibbon: A small, slender ape with long arms.

habitat: The area or natural environment in which an animal or plant normally lives, such as a desert, coral reef or freshwater lake. A habitat can be home to thousands of different species.

juvenile: Young, sub-adult animals. These are older than “babies” or larvae, but not yet mature enough to be considered an adult.

native: Associated with a particular location; native plants and animals have been found in a particular location since recorded history began. These species also tend to have developed within a region, occurring there naturally (not because they were planted or moved there by people). Most are particularly well adapted to their environment.

palm: A type of evergreen tree that sprouts a crown of large fan-shaped leaves. Most of the roughly 2,600 different species of palms are tropical or semitropical.

population: (in biology) A group of individuals from the same species that lives in the same area.

primate: The order of mammals that includes humans, apes, monkeys and related animals (such as tarsiers, the Daubentonia and other lemurs).

species: A group of similar organisms capable of producing offspring that can survive and reproduce.