Analyze This: Sharks aren’t as scary as what you see on TV

Shark Week shows give mixed messages about the animals

Sharks may seem scary because of what’s on TV or in movies. But you’re more likely to be struck by lightning than to be bitten by a shark.

Image Source/Getty Images

You can hear it in the eerie music. Or in the narrator’s tone. Something bad is going to happen. On Shark Week, a week of documentary-style shows on cable TV, suspenseful sounds often cue tales of terrifying shark attacks.

But such incidents are rare, says Lisa Whitenack. She’s a biologist and geologist at Allegheny College in Meadville, Pa. “You are more likely to get hit by lightning than to be bitten by a shark,” she says. More people die annually because of fireworks accidents than shark attacks. People swimming in the ocean are in sharks’ homes, Whitenack notes. And as long as sharks aren’t provoked, they usually leave people alone.

Whitenack and other shark scientists were concerned that the scary stuff on Shark Week was misrepresenting sharks. They also suspected that Shark Week didn’t contain much science and didn’t reflect the diversity of shark researchers. She and her colleagues set out to gather data on their hypotheses. “Because that’s what good scientists do,” she says.

Her team watched 201 episodes of Shark Week. For each 40-minute episode, the researchers kept tabs on which species of sharks appeared, who was speaking, what they said and more. The team also analyzed the research methods cited in the shows.

Shark Week often gave muddled messages, the researchers reported July 22 at the American Elasmobranch Society Annual Meeting. That meeting was in Phoenix, Ariz. Over half of the shows gave both positive and negative messages about sharks. And “in some cases, we saw stuff that was just not true or was exaggerated,” Whitenack says. “That creates fear.” For instance, one episode focused on possible encounters with a prehistoric shark. “The entire episode was fiction,” Whitenack says. But many viewers missed a message about the show’s staged events and thought the extinct creature could be alive today.

Often, the people talking about sharks on these shows weren’t scientists. And the experts featured were usually white males. That doesn’t accurately represent the variety of people who study sharks, Whitenack notes. Also, Shark Week claims to provide information about protecting and conserving sharks. Many shark species are rare and endangered. But the team found that only six episodes gave viewers ways to help sharks. “The messaging needs some work,” Whitenack concludes.

Just like scientists, viewers can and should ask lots of questions. With a bit of digging, people may be able to fact-check what they’ve heard on TV. “Don’t take it all at face value,” Whitenack cautions. “Just because it’s on TV doesn’t mean it’s true.”

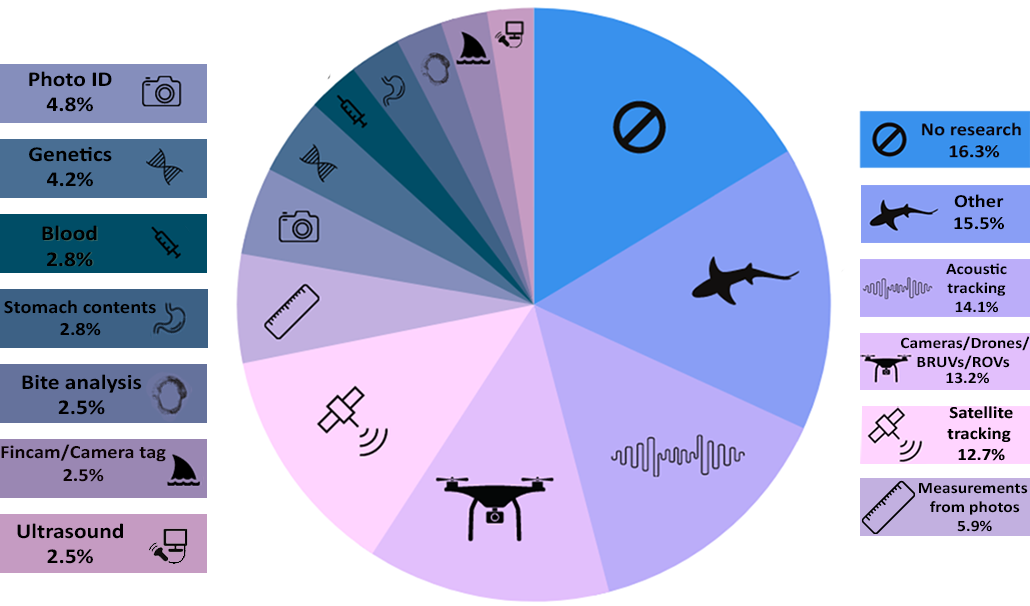

Research methods featured on Shark Week episodes

Researchers watched over 200 episodes of Shark Week, filling out a worksheet on each one. They tallied up all the research methods mentioned. The category “other” includes methods that were only used once, such as research that measured how sharks’ muscles worked.

Data Dive:

- What is the largest slice of the pie chart?

- Why does it matter that this is the most-cited method in Shark Week shows?

- How many slices on the pie chart relate to the use of photos or videos? Add them up. What’s the total percentage?

- What sort of information about animals can researchers get from photos and videos? What kinds of information will they miss?

- How many slices on the pie chart relate to measuring animals? What’s their total percentage?

- What is the percentage of methods that analyze samples — DNA, blood, or stomach contents?

- Which methods track where animals travel? What’s the total percentage?