An ancient childhood

Knowing what the lives of children were like long ago can help us understand how cultures and societies change.

By Emily Sohn

History books are full of facts about adults. In school, you learn about the wars that grown-ups have fought, the kingdoms they’ve built and destroyed, and the cultures they’ve created.

What about all the kids?

“Based on the research I’ve done, kids have been ignored,” says Jamie Anderson Waters. She’s an anthropologist at the University of Florida in Gainesville.

|

|

Jamie Waters examines a carved bird that might have been used as a toy by children in 18th-century Spanish colonial households in St. Augustine, Florida.

|

| AP Photo/University of Florida/Ray Carson |

The little people of the past deserve more attention, Waters says. As part of her graduate studies, she used archaeological evidence to look at what childhood was like hundreds of years ago in a city in Florida called St. Augustine.

Our current view of children has an adult bias, Waters says. “We think they’re not really part of the culture,” she adds. “They’re just little entities there to be taught. They’re not shaping the culture themselves.”

Her findings show that adults aren’t the only ones who contribute to society. Kids grow up to lead the next generation. Knowing what their lives were like long ago is essential if you want to understand how times and cultures have changed.

Old city

St. Augustine turned out to be an ideal place to study ancient childhoods. People have lived there for a longer continuous stretch of time than in any other city in what is now the United States.

|

|

St. Augustine is a city on the shore of the Atlantic Ocean in the northeastern part of the state of Florida in the United States.

|

Just south of Jacksonville, St. Augustine was first settled in 1565. The residents of the city left behind good records of their lives over the last 500 years, and many of their belongings have been collected and preserved.

Researchers have already dug up the remains of more than 15 houses that stood between 1565 and 1820, Waters says. She used church records to determine where people lived, how many children they had, and how much money they made.

For her project, Waters focused on people living between 1700 and 1760. She looked at eight homes—four with children and four without. In each group, two of the houses belonged to rich families, while the other two belonged to lower-class families.

Toys and beads

Waters looked at all the objects recovered from each household, and she picked out the ones that most likely belonged to kids.

|

|

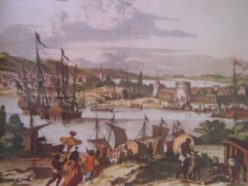

St. Augustine, Florida, in 1760, while under Spanish control.

|

She identified a large number of toylike objects, including marbles, little clay figurines, tiny ceramic bowls, a bug made out of metal wire, figures carved out of bird bones, and thimbles too small to fit on an adult’s finger.

Parents might have used some of these objects to help prepare their children for adulthood. Others must have been purely for fun. Games that adults play (such as checkers) showed up, too, but houses with kids had more of them than houses without kids.

|

|

Marbles, game disks, doll parts, and toothbrush from St. Augustine.

|

| Image courtesy of the Historical Archaeology Collections of the Florida Museum of Natural History |

Waters also found lots of beaded amulets in the St. Augustine archives. Based on historical data about Florida’s Spanish settlers, she concluded that people used these amulets to protect themselves from evil.

Certain types of beads were thought to keep children from getting sick. Amber, for instance, was supposed to help infants when their teeth started to grow in. And mothers wore white stones while they were breastfeeding. In St. Augustine, these types of beads were more common in homes with kids.

|

|

Public square, St. Augustine, Fla., around 1858.

|

One item that caught Waters’ eye was a 2-inch-long, smooth, rounded piece of glass. She identified it as a type of pacifier. No one else had realized what the object was. “I don’t think anyone was looking at these items with kids in mind,” she says.

Richer families had more toys, Waters found. Even so, the widespread occurrence of kid-friendly items showed that children were important to all families, no matter how much money they made.

“Even in the poor households,” she says, “children were still valued enough that their parents found things to buy or make for their amusement.”

Studying childhood

Some experts argue that there was no such thing as “childhood” until the 1800s. Waters disagrees.

In a 1560 painting called “Children’s Games,” Belgian painter Pieter Bruegel showed kids playing 75 different games, such as rolling barrel hoops, playing leap-frog, wrestling, doing handstands, and making mud pies. Sounds a lot like recess today, doesn’t it?

A small number of researchers are now looking into various aspects of the history of childhood. Waters wishes that even more would join in. “Whenever people talk about the past, they tend to ignore a good chunk of the population,” she says.

After all, there’s a lot left to learn about the roles that kids played in helping shape a society or culture. Think of how much influence you already have in today’s world—with your video games, pop stars, movies, cell phones, and other amusements.

There have always been kids around to make things interesting for adults.

Going Deeper: