Ancient heights

Leaf fossils can help track the rise and fall of mountain ranges.

By Emily Sohn

You probably know where all the hills are in your neighborhood. Even so, the planet hasn’t always had the same lumps. In some places, Earth was even lumpier that it is now. In other places, it was smoother. Over millions of years, entire mountain ranges have come and gone. The landscape is always changing.

Now, a geologist from the Field Museum in Chicago says that she has found a new way to figure out how the shape of Earth’s surface has changed over time. Her strategy? Leaf peeping.

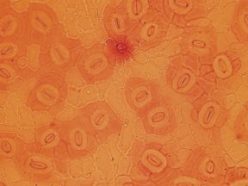

A tree’s leaves have tiny holes called stomata. These pores allow the leaves to take in a gas called carbon dioxide, which the tree needs in order to survive.

With this fact in mind, geologist Jennifer McElwain collected leaves from living California black oak. These trees grow in a wide range of altitudes, from sea level all the way up to 2,500 meters (8,200 feet).

McElwain used a microscope to count how many stomata were inside a given area of each leaf. She found that the leaves had more stomata at higher altitudes. Then, she came up with an equation that links stomata numbers and elevation.

The black oak has been around for at least 24 million years. So, scientists can now count stomata on fossilized leaves to figure out how high the trees were when they lived, McElwain says. By comparing this altitude with the altitude at which the fossils were collected, the researchers can measure any changes in elevation that had occurred.

The new method should be more accurate than previous methods, McElwain says. Next, she wants to come up with equations for other tree species.

Someday, she says, her research may help scientists answer a major question in geology: When did the Himalayas in Asia rise?

Going Deeper:

Shiga, David. 2004. Ancient heights: Leaf fossils track elevation changes. Science News 166(Dec. 18&25):390. Available at http://www.sciencenews.org/articles/20041218/fob7.asp .

You can learn more about leaf pores (stomata) at www.microscopy-uk.org.uk/schools/images/stomata.html (Microscopy-UK) and www.accessexcellence.org/AE/AEC/AEF/1994/case_leaf.html (National Health Museum).

Information about the geology of the Himalayas can be found at jan.ucc.nau.edu/~wittke/Tibet/Himalaya.html (Northern Arizona University).