anatomy: (adj. anatomical) The study of the organs and tissues of animals. Or the characterization of the body or parts of the body on the basis of structure and tissues. Scientists who work in this field are known as anatomists.

anthropologist: A social scientist who studies humankind, often by focusing on its societies and cultures.

ape: A group of rather large primates, all of which lack a tail. They include gorillas, chimpanzees, bonobos, orangutans, gibbons and humans. Most people tend to group humans into their own separate subcategory owing to a number of special traits. These include a larger brain, greater mental abilities (including being able to talk) and their ability to walk on two legs.

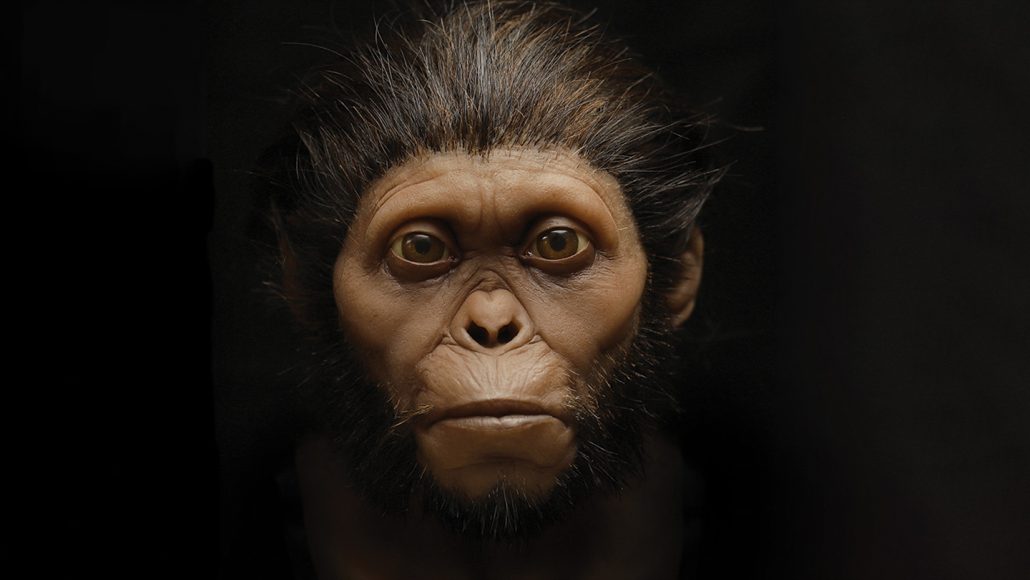

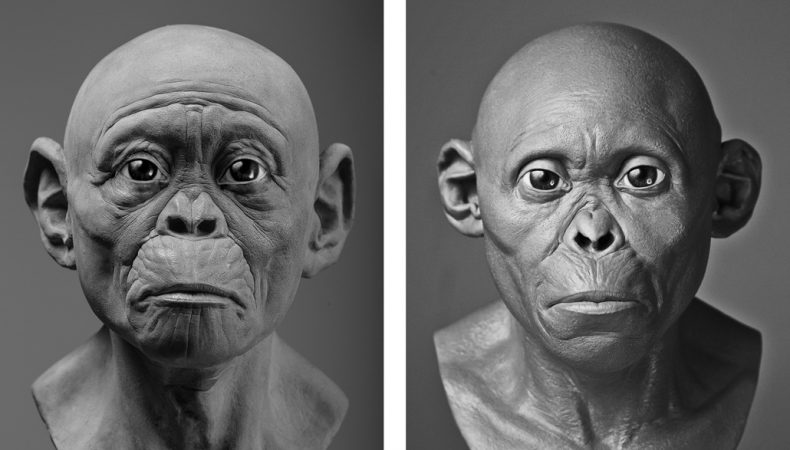

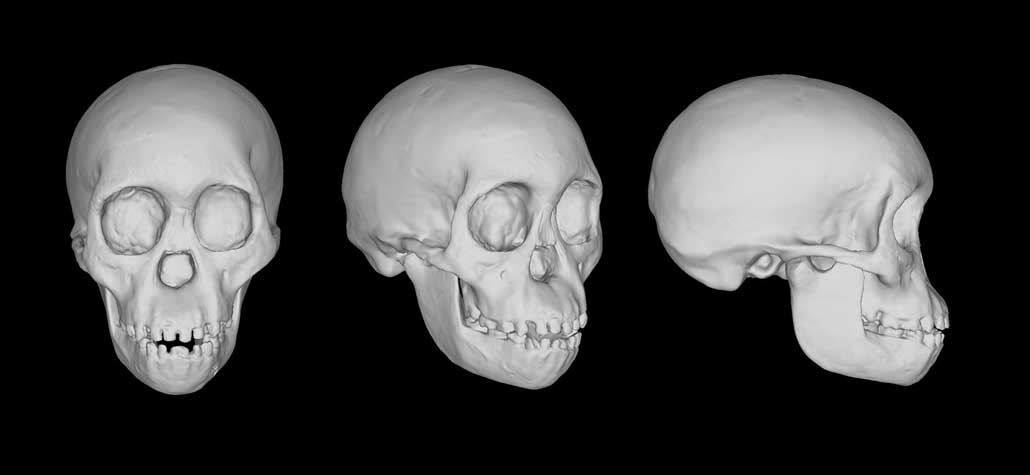

Australopithecus: An extinct genus of hominids that lived in East Africa from about 4 million to 2 million years ago.

behavior: The way something, often a person or other organism, acts towards others, or conducts itself.

bias: The tendency to hold a particular perspective or preference that favors some thing, some group or some choice. Scientists often “blind” subjects to the details of a test (don’t tell them what it is) so that their biases will not affect the results.

data: Facts and/or statistics collected together for analysis but not necessarily organized in a way that gives them meaning. For digital information (the type stored by computers), those data typically are numbers stored in a binary code, portrayed as strings of zeros and ones.

database: An organized collection of related data.

DNA: (short for deoxyribonucleic acid) A long, double-stranded and spiral-shaped molecule inside most living cells that carries genetic instructions. It is built on a backbone of phosphorus, oxygen, and carbon atoms. In all living things, from plants and animals to microbes, these instructions tell cells which molecules to make.

ecology: A branch of biology that deals with the relations of organisms to one another and to their physical surroundings. A scientist who works in this field is called an ecologist.

extinct: An adjective that describes a species for which there are no living members.

family: A taxonomic group consisting of at least one genus of organisms.

fossil: Any preserved remains or traces of ancient life. There are many different types of fossils: The bones and other body parts of dinosaurs are called “body fossils.” Things like footprints are called “trace fossils.” Even specimens of dinosaur poop are fossils. The process of forming fossils is called fossilization.

great ape: A term for most apes (large primates that lack a tail). These include gorillas, chimpanzees, bonobos, orangutans and humans. Most scientists tend to group humans into their own separate subcategory owing to a number of special traits. These include a larger brain, greater mental abilities (including being able to talk) and their ability to walk on two legs. The only “lesser” ape is the gibbon.

groom: (in zoology) The practice of some animals to clean another, usually in places the groomed animal can’t see or reach, such as the back, head or face. Sometimes a groomer will remove ticks or other parasites. Other times it might remove tangles in fur or debris such as leaves. The attention the groomed animal receives can be calming and is usually accepted only from a family member or close member of its social group.

hominid: A primate within an animal group that includes humans and their ancient upright-walking relatives. Some scientists also include today's chimpanzees, gorillas and orangutans.

intelligence: The ability to collect and apply knowledge and skills.

intuition: The ability to understand some issue — or feel one confidently knows something — without having to consciously analyze it. Some people refer to it as a “gut feeling” that something is true. In fact, it’s based on an unconscious analysis of past experiences that may relate to the issue.

muscle: A type of tissue used to produce movement by contracting its cells, known as muscle fibers. Muscle is rich in protein, which is why predatory species seek prey containing lots of this tissue.

Neandertal: A species (Homo neanderthalensis) that lived in Europe and parts of Asia from about 200,000 years ago to roughly 28,000 years ago.

prejudice: From the phrase "pre-judged," it is a usually negative attitude towards one or more people owing to their belonging to some group (typically defined by race, religion or ethnicity). Prejudice towards some particular race is known as racism. Prejudice against one gender (usually women) is termed sexism. Prejudice against the elderly is referred to as agism.

skull: The skeleton of a person’s or animal’s head.

species: A group of similar organisms capable of producing offspring that can survive and reproduce.