An ancient ichthyosaur graveyard may have been a breeding ground

This suggests the ancient giants had favorite breeding spots, much as modern whales do

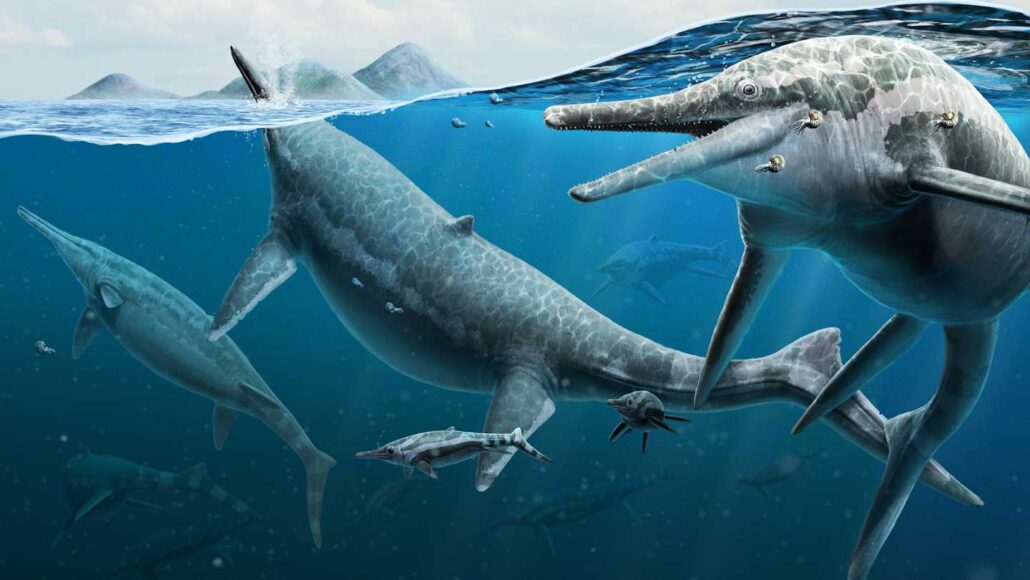

For generations, ancient dolphin-like reptiles called ichthyosaurs (illustrated) may have returned to their favorite safe waters to breed.

Gabriel Ugueto/Smithsonian

Many modern whales are creatures of habit. They return to the same spots each year to breed. Now, fossils hint that ancient ichthyosaurs, dolphin-like reptiles, did the same thing.

The fossils were found in a mysterious ichthyosaur graveyard.

About 230 million years ago, that area was covered by a tropical sea where the reptiles swam. Today, that site is part of Nevada. It contains the world’s richest collection of fossils from Shonisaurus popularis. (It’s one of the largest known ichthyosaurs.) A new look at the fossils suggests that many generations of S. popularis may have used this area as a breeding ground.

Researchers shared their discovery December 19 in Current Biology.

“This is something we see in modern marine vertebrates,” says Randall Irmis. A paleontologist, he works at the National History Museum of Utah. That’s in Salt Lake City. He notes that “gray whales make [the] trek to Baja California every year” to breed. Its sheltered, warm water offers safety for the whales. The new finding shows that this shelter-seeking behavior “goes back at least 230 million years,” Irmis says. “It really connects the past to the present in a big way.”

Erin Maxwell is a paleontologist but wasn’t involved in the new research. She works at the State Museum of Natural History in Stuttgart, Germany. Scientists thought ichthyosaurs might have had special birthing areas, she says. This study “is the first to support these speculations with data.”

An ancient mystery

For decades, Nevada’s ichthyosaur fossil trove has puzzled scientists. One reason is the sheer number of ichthyosaur fossils there. Another is that almost all came from one species — the school bus–sized S. popularis. Also, no one knows what killed them all.

All told, Irmis and others in his team identified 112 ichthyosaurs across the ancient graveyard. Some were at a site where the bones had been left half-encased in rock (for public viewing). That snapshot of ichthyosaur death let scientists see how the fossils were situated. That, in turn, offered clues to the reptiles’ behavior.

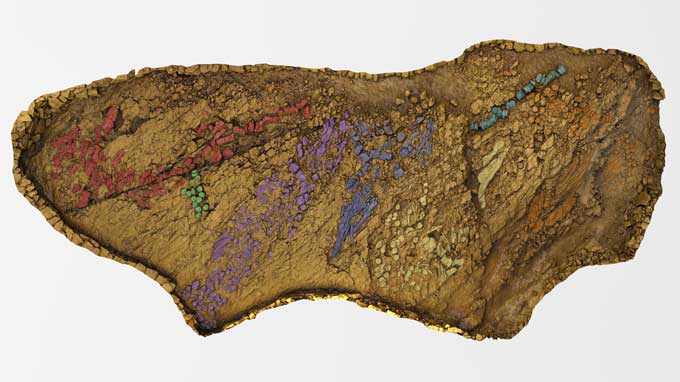

The researchers inspected the half-buried reptiles using cameras and a laser scanner. Those data helped construct a 3-D model of the bone bed. The team studied the sizes and shapes of bones from across the whole reptile graveyard. They also analyzed the chemical makeup of the surrounding rocks. They even peered at old photographs and field notes about the site.

These scraps of evidence helped the researchers understand what they were looking at. The results may solve at least one long-standing mystery: What brought these creatures together?

A place of birth and death

Almost all of the Shonisaurus skeletons were fully grown adults. There also were a few remains from very tiny ichthyosaurs. X-rays of the itty-bitty fossils offered a glimpse inside. Their interior features showed that some tiny bones came from embryos and infants.

This led the team to conclude that the site was a birthing ground. That could be why so many of the same creatures not only were in one place but also alongside newborns. This site seems to have been a birthing ground for a long time. Some of the bones were at least hundreds of thousands of years older than others.

As for what killed these dino-cousins: “We don’t know,” Irmis says. The rock chemistry data now rule out harmful algal blooms or volcanic eruptions as culprits.

Some of the animals could have still died at the same time. Gathering in one place to breed may have left these reptiles vulnerable to a catastrophe. For instance, an undersea landslide could have wiped out a bunch at once.

But many generations of ichthyosaurs came to this place again and again. So, maybe their bodies just piled up — one at a time — over millennia.