Science is just starting to understand what animals feel

Researchers are finding creative ways to tease out what animals experience

These dogs look really happy. But people often misjudge cues about what emotions animals are feeling.

Ilka & Franz/Stone/Getty Images

A dog senses a nearby stranger and gives a protective bark. A haughty cat slinks by, ignoring everyone. A cow chews its cud and moos in contentment. At least, that’s how we may interpret their actions. We take our own experiences to understand and relate to the animals around us — using our imagination to fill in any gaps along the way.

But such assumptions are often wrong.

Take horse play. Many people assume these animals roughhouse for fun. But in the wild, adult horses rarely play. When captive horses play, it isn’t necessarily good, says Martine Hausberger. She’s an animal scientist with the French National Center for Scientific Research (or CNRS). Her lab is at the University of Rennes.

Hausberger raises horses on her farm in Brittany, France. About 30 years ago, she noticed that people who keep horses often misjudge cues about the animals’ behavior. That inspired her to study horse welfare.

Adult horses that play have often been restrained, she found. Play seems to relieve the stress from that restriction. “When they have the opportunity, they may exhibit play. And at that precise moment they may be happier,” she says. But “animals that are feeling well all the time don’t need this to get rid of the stress.”

Scientists who study animal behavior and welfare are coming to understand how many creatures experience the world. “In the last decade or two, people have gotten bolder and more creative in terms of asking what animals’ emotional states are,” explains Georgia Mason. She studies animal behavior and welfare at the University of Guelph in Ontario, Canada.

Researchers like Mason are getting insight into a wide range of animals. For instance, recent studies hint that picking up a mouse by its tail can ruin its day. Meanwhile, an unexpected sugar treat may boost a bee’s mood. Crayfish might feel anxiety. Ferrets can get bored. Octopuses — and perhaps fish — can feel pain.

Knowing all this could begin to change how we treat animals.

Yet studying what animals feel and experience is a challenge, notes Charlotte Burn. This animal-welfare scientist works at the Royal Veterinary College in Hatfield, England. People can try to learn how animals feel based on clues from their bodies and their behaviors. But feelings are personal. “So doing science about this is a bit strange,” Burn says. “You have to get comfortable with the fact that your key thing is unknowable.”

Horse sense

To study horse welfare, Hausberger doesn’t focus on fleeting emotions such as if they are happy or sad. She’s interested in a horse’s overall emotional health — meaning how good or bad it feels in the long run.

To measure how content a horse is, people often look at its posture or the position of its ears. They might also consider how attentive the horse is to what’s going on around it. Appetite and its immunity can shed light on a horse’s overall wellness. And certain chemicals in its blood can point to persistent stress.

Recently, Hausberger was part of a team that tested a more direct measure of horse well-being. They looked at brainwaves. To do this, the scientists built a simple, portable device worn as a headset. It provides “a sort of summary of brain activity,” she says. Five electrodes on a horse’s forehead eavesdrop on its brainwaves.

The researchers used this headset to gauge the welfare of 18 horses. Each wore the device for six 10-minute sessions. The results offered a snapshot of the horses’ secret inner lives. Hausberger’s team shared what it found in the March 2021 issue of Applied Animal Behaviour Science.

Horses that roamed with their herd, grazing outdoors at will, had more theta brainwaves. In people, theta waves seem to reflect a calm well-being. By contrast, animals that lived in solo stalls had little contact with other horses. These horses had more gamma brainwaves. Some studies in people have linked gamma waves to anxiety and stress.

Shared evolutionary history

For a long time, scholars didn’t think animals had feelings. Biologist Charles Darwin bucked that trend. In 1872, he proposed that many species could have evolved emotions. Take fear. In almost all animals, he wrote, “Terror causes the body to tremble.”

But even 25 years later, researchers found it impossible to know the inner lives of animals. So, they concluded it wasn’t worth looking into. Says Mason, they basically argued that “if you can’t measure it, don’t make up stories about it.”

That started to change near the end of the 20th century. In the 1980s, for instance, Marian Stamp Dawkins began probing animal experiences. She studied animal welfare at the University of Oxford in England. Her research gave creatures a chance to show what they wanted and how much they’d “pay” to get it. Researchers still ask such questions. For instance: How heavy a door would a hen push for the chance to perch at night?

Another way to study animal feelings is based on human psychology. Scientists can look for parallels in how people and other animals process their experiences. That could offer clues to what animals feel.

Why do scientists think this could work? Well, researchers already use rodents, fish, primates and other animals to better understand ourselves. These animal models can help them study and develop drugs for mental illnesses. So, the opposite should also work, says Michael Mendl. Scientists should be able to use what they know about feelings in people to study those in other animals. Mendl is an animal-welfare scientist at the University of Bristol in England.

Mood matters?

Mendl has focused on one well-known feature of human psychology: affect. This term describes someone’s overall mental state. Affect can be positive or negative. Good or bad experiences can often shape someone’s affect. And affect can then shape how people see the world, biasing their thoughts and decisions.

Mendl and his colleagues tried to find out if the same was true for rats. They tested whether experiences that might influence a rat’s affect would change its decisions.

First, the team taught rats to expect the sound of one beep would precede a good outcome: a tasty treat. The team taught rats to link another tone with a bad outcome: a harsh noise. Rats learned to press a lever when they heard the good tone — and not to when they heard the other tone.

Then, the researchers placed the animals in either an environment they found pleasing or in one that annoyed them. A few days later, the researchers played a neutral beep for each animal. Its pitch was midway between what they had earlier learned as good and bad tones.

Animals that had lived in the pleasing cage now pressed the lever. This hinted that they interpreted the neutral beep as a good sign. They hoped that pressing the lever would reward them with a treat. Meanwhile, rats that lived in the annoying cage left the lever alone or were slower to press it. This suggested they did not interpret the neutral beep as signaling they were about to get a reward.

Those behaviors, Mendl explains, suggest that how rats judged the tone was based on whether they felt good about the world.

Since that study, researchers have done similar tests on affect in at least 22 species. Those included other mammals, birds and insects.

There’s an important limit to this experiment, however. Its results only suggest whether an animal feels good or bad about some experience, Mendl explains. It does not prove something more basic: whether the animal can have subjective experiences. And by subjective, he means ones that are personal and colored by their own inner lives. This would be in contrast to responses they have to external events or stimuli — responses that all members of their species would likely share.

This type of study assumes that animals are sentient — or aware of their own feelings and experiences. If they aren’t, then studying animals’ well-being wouldn’t make sense, says Mason at Guelph. “But none of the measures we use can assess or check that assumption,” she says. And the reason, she adds: “We simply don’t yet know how to assess sentience.”

Searching for emotional life

Some animal experiences may vary by species. Take animals that live in groups, such as sheep. For them, Mason says, isolation “probably induces a form of terror that … humans can’t imagine.” Or think of creatures, such as homing pigeons, that can sense magnetic fields. For them, being put in a strong magnetic field “may be very upsetting in a way that we don’t have a name for,” she explains.

But many other feelings could be shared. For example, lots of evidence suggests that the stress of captivity can cause symptoms of depression in animals.

What about boredom? Mason and her colleagues proposed a way to tell the difference between depressed animals and bored ones. A depressed animal loses interest in its surroundings, they reasoned. A bored animal might be drawn to both good and bad experiences — anything to break the monotony.

And that’s what the group showed in 2012.

Male minks sought out a mix of good and bad experiences. They were drawn to the smell of female poop, a treat during mating season. But the minks also showed interest in neutral scents, such as plastic bottles. They even perked up at threatening smells such as the leather gloves that farmers had used to catch minks.

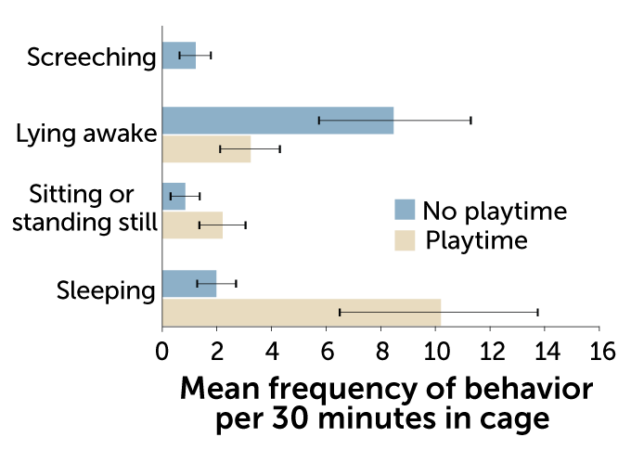

Burn found something similar in ferrets living in a lab. The animals sought out the pleasure of a good whiff of mouse bedding. But they were also attracted to the bad smell of peppermint oil. Relieving the animals’ boredom with extra playtime turned their interests away from negative things. Burn and her colleagues shared their findings in February 2020 in the journal Animal Welfare.

Relieving boredom

Ferrets living in lab cages got extra playtime (below, left) to reduce boredom on some days — but not on others. On days they got no extra playtime, they more often screeched and lay awake with their eyes open. They also slept and stood less. This rise in restless behavior may indicate higher levels of boredom.

Playtime reduces stimulus-seeking behavior in ferrets

Pain in two parts

Pain is another experience that animals share. Pain has two aspects, notes Matthew Leach. He studies animal behavior and welfare at Newcastle University in England. One part of pain is physical. It simply reflects when pain receptors in the body turn on. Animals respond to it as a reflex or due to a basic learned response. No conscious awareness is needed.

The other part of pain is emotional. And this part is trickier to measure. The reason is that it shows up in more complex behaviors. For instance, mice prefer a temperature up to 10 degrees Celsius (18 degrees Fahrenheit) warmer than they find in most research labs. So, the rodents build intricate nests in their cages to stay cozy. But when in pain or distress, the animals’ nest-building abilities fall apart.

Facial expressions are a more direct way to assess pain or other distress in animals, Leach says. His group and others have identified a range of expressions in more than a dozen species, from mice to horses. With less than 30 minutes of training, people can learn to spot the twisted grimace of pain on animals’ faces, Leach says.

And their faces can reveal much more than pain. Artificial-intelligence systems have helped identify a whole range of emotions in videos of mice. They’ve spotted pleasure, disgust and fear. Those feelings are visible in the tilt of a mouse’s ears or a curl of its nose. “We’re still very much in the infancy of understanding what facial expressions are telling us,” Leach says.

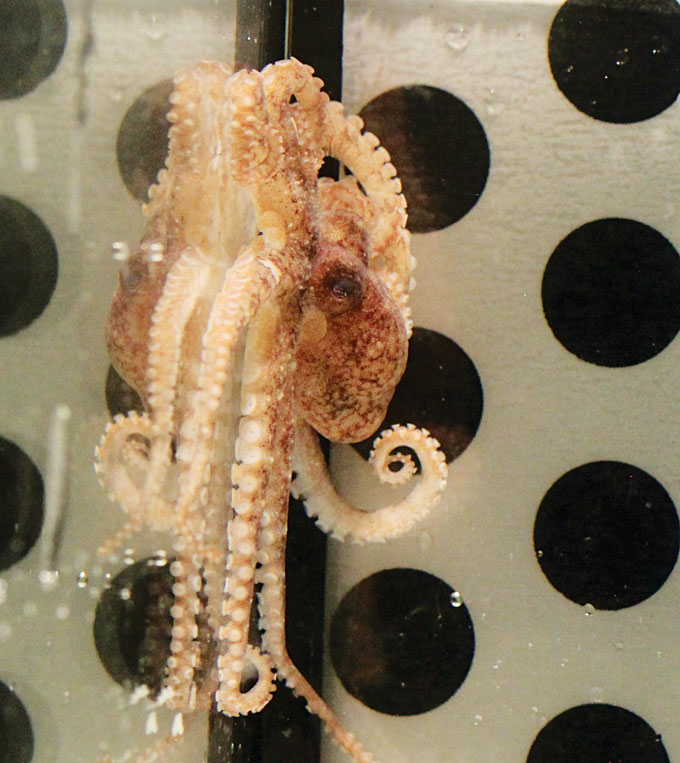

Researchers can often use an animal’s behavior to tell if it is in pain. But recognizing pain in animals that are very different from us is hard, says Leach at Newcastle. Take octopuses. With their three-lobed brains, they are “as far from a vertebrate as you could possibly ever get,” he says. So octopuses may experience things quite differently.

Neuroscientist Robyn Crook has explored that. She works at San Francisco State University in California. In one test, she let octopuses loose in a box with three rooms. Each octopus naturally wandered into a room it preferred. Then Crook injected the animals with a slightly painful acid. Some octopuses were also injected with pain-relieving medicine. Others were not.

Crook put the animals that got only the acid shot into the chamber they had preferred most. The ones injected with acid and the pain killer were put in the chamber they had liked least. The goal was to get the octopuses to associate how they felt with these chambers.

A few hours later, the pain from the acid would have worn off. Now Crook let the animals explore the three rooms again. The octopuses that got the painful shots avoided the room they had first preferred. This suggested they now link this room with pain. Those that got the shots with the medicine now preferred the room they had disliked at first. This suggested they now associate this room with relief from pain.

Crook’s team shared its findings February 2021 in iScience. Their results hint at emotional awareness in octopuses, Crook says. But not everyone agrees. “It is very difficult,” she admits, “to produce convincing evidence of [this] in an animal that’s very unlike us.”

A matter of ethics

From an ethical point of view, treating octopuses as if they feel pain “is wise and humane,” Mason says. But researchers are still figuring out where to draw the line for different animals.

That question recently prompted scientists in the United Kingdom to survey research on animal sentience. They reviewed all the evidence they could find on cephalopods (octopuses and related animals) and crustaceans (shellfish such as shrimp). This involved looking at studies on their brains and behavior. The researchers also looked at common practices in the seafood industry.

The group had a checklist of things that could qualify an animal as sentient. One was whether its nervous system could combine different types of sensory information. Another was the complexity of an animal’s pain-sensing system.

This research showed that certain invertebrates such as crabs, lobsters and octopuses should be considered sentient. Although it’s impossible to be sure, it appears they might be able to experience pain and suffering. So “the body of evidence is starting to make us think [such animals] deserve the benefit of the doubt,” Burn says.

In light of that, animal-welfare laws may need to start protecting these creatures. In fact, updates to U.K. animal-welfare laws may make it illegal to boil lobsters alive. The new rules would require swifter, less painful methods to kill the animals.

There is still much to learn about animals’ emotional states — and on a more basic level, sentience. But that research could help us take better care of the animals who share our planet. It also could give us a new perspective on how much of our inner life is shared across the animal kingdom.