Answers to your questions on the new coronavirus

As the global health epidemic of COVID-19 spreads, many details remain unknown

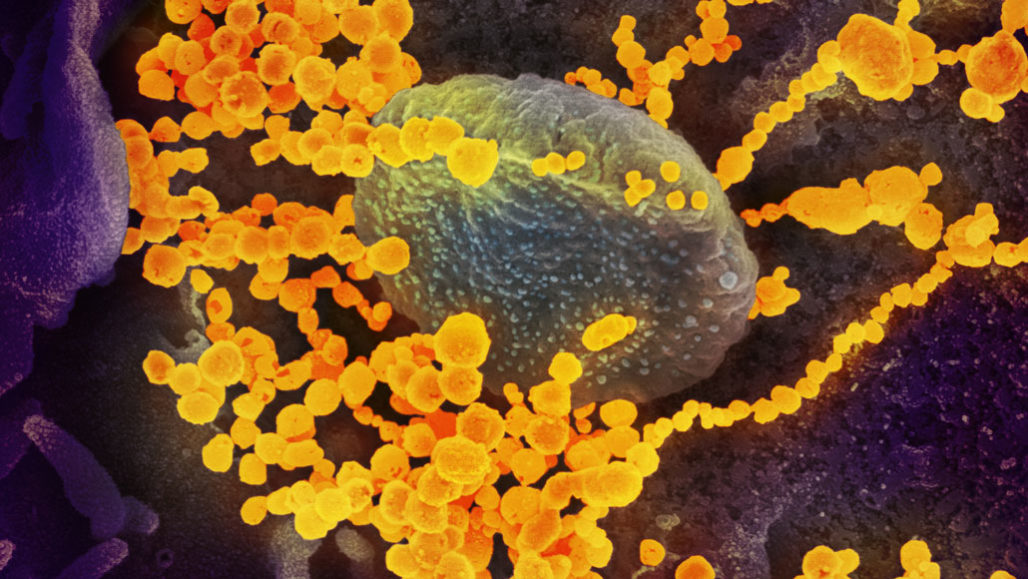

The new coronavirus (round yellow objects in this scanning electron microscope image) is called SARS-CoV-2. The disease outbreak it has triggered began in China and has since spread to more than 70 other nations.

NIAID-RML

Updated

This story is being updated as news develops during this crisis. The last update was on Friday, April 3.

A new coronavirus has infected more than 1,033,000 people since December 2019. As it rapidly spreads across the planet, scientists and public-health experts are racing to limit the share of people it infects. To do that, they need to understand the new virus. It’s called severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2, or SARS-CoV-2. Many questions remain unanswered about this new virus. Fortunately, details are starting to surface.

Here’s what we know so far about the virus and the disease it causes. Check back regularly as we will be updating these answers as more information emerges.

Do you have questions about the new coronavirus that you’d like answered? E-mail them to feedback@sciencenews.org.

Some of the questions below include:

- What is SARS-CoV-2?

- Why are experts so worried about it?

- How deadly is it?

- Who’s most at risk? What about young children?

- How do people die from it?

- Can people who have had the virus be reinfected?

- What’s the situation in the United States?

- What can I do to prepare?

- Does hand sanitizer actually work?

- Why are masks now recommended for the public?

- What should I do if I think I have COVID-19?

- When will it end?

What is SARS-CoV-2?

The virus is a novel type of coronavirus. This is a family of germs that typically causes colds. But three members of this viral family can cause life-threatening disease. They are severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV), Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV), and now SARS-CoV-2. The newest of these got its name because it is similar to SARS-CoV.

The disease SARS-CoV-2 causes is coronavirus disease 2019, or COVID-19. Early in the outbreak, it was temporarily called 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV).

Why are experts so worried about it?

Doctors still aren’t sure how contagious the virus is, nor how deadly. As a new coronavirus, it hadn’t infected people before the outbreak in China. Because it is new, people’s immune systems don’t have experience fighting the virus. So for now, everyone is susceptible to infection. And the disease can spread rapidly and widely.

Scientists and public health officials worry especially about people in high-risk groups. So far, older adults and people with underlying health conditions (such as heart disease, asthma and lung disease) appear at risk for a more severe case of COVID-19.

In several countries, there has been a sudden, big spike in cases. That has happened in the United States, where COVID-19 patients now have to compete for hospital space with other sick people. Too big a spike could overwhelm hospitals.

So how deadly is the new virus?

Most cases have been mild. Of people who contract the virus, an estimated 3.4 percent die, according to the World Health Organization. Officials say the number will probably change as the outbreak continues and will vary from place to place.

As of April 3, there have been more than 1 million confirmed cases worldwide and more than 55,000 confirmed deaths, according to data from Johns Hopkins University. Over 220,000 people are reported to have recovered from the virus.

For comparison, the 2003 SARS outbreak was far more deadly. But because it sickened fewer people overall, its death toll never rose above 774. The virus that causes MERS, a disease that still circulates in the Middle East, is even more deadly. It kills one in every three people it infects — or 866 people so far.

The true, overall deadliness of COVID-19 may not be known for a while. Researchers will need to find out how many people have been infected but showed no symptoms (or had such mild symptoms they didn’t get tested).

Who’s most at risk? What about young children?

Early data from China suggested that adults aged 60 or older are most vulnerable. More recent data from around the world support that. They show that older people, especially those with heart disease and other diseases such as asthma, chronic lung disease or severe obesity, are at higher risk for severe illness.

For some reason, children and teenagers seem to rarely become seriously ill with COVID-19. Yet even children with mild illness may still spread the virus.

One March 16 study in Pediatrics focused on this. It described COVID-19 in 2,143 children in China. About half lived in Hubei Province, the epicenter of the pandemic. Compared with adults, these children generally had milder cases. It’s unknown why most kids aren’t getting as sick as adults are.

But children aren’t wholly protected. An estimated 6 in every 100 kids had severe or critical disease. Infants and preschoolers generally had more severe illnesses than older kids, the team found. Their symptoms including trouble breathing. The researchers report that one 14-year-old boy even died.

What are the symptoms?

People with COVID-19 often have a dry cough and sometimes shortness of breath. The broad majority of patients will also spike a fever, according to reports on patients in China.

One tricky thing is that these symptoms also apply to the flu.

Respiratory illnesses caused by other types of viruses (such as rhinoviruses and enteroviruses) usually do not cause fevers, notes Preeti Malani. She’s an infectious disease specialist at the University of Michigan School of Medicine in Ann Arbor. Colds often include a runny nose. So far, however, COVID-19 has not left many people with drippy noses.

Though many people infected with SARS-CoV-2 will probably have mild symptoms, others may develop life-threatening pneumonia. Here, tiny air sacs in the lungs can become inflamed and fill with fluids, even pus. Symptoms of pneumonia can include chest pain when breathing or coughing, fever, a phlegmy cough, shortness of breath and more.

How do people die from COVID-19?

Coronaviruses usually cause fairly mild illness in the nose and throat. But as with SARS and MERS, the new virus works its damage much deeper in the respiratory tract. SARS-CoV-2 leads to “a disease that causes more lung disease than sniffles,” explains Anthony Fauci. He directs the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases in Bethesda, Md. It’s that damage to the lungs that can turn these illnesses deadly.

Patients with COVID-19 generally die from breathing difficulties and the failure of several organs, such as the heart. Those organs fail partially because of what the virus does, but also because of how the body’s immune system attacks the infection. The virus that causes COVID-19 attacks cells within the respiratory tract, especially the lungs. As these cells die, they fill the lungs’ airways with fluid and debris. Meanwhile, the virus hijacks living cells there to replicate. All of this overwhelms the lungs, making it hard to breathe.

The presence of dying cells and a replicating virus also sparks the immune system to react to the germs. Immune cells flood the lungs. There, they attempt to repair damaged tissues and wipe out the virus. This immune response usually is well controlled. However, it can sometimes go berserk and damage healthy cells as well as attempting to remove dying ones. A flood of signals from the immune system, called a cytokine (SY-tuh-kyne) storm, can damage tissues so badly that the lungs and other organs can simply give out.

The new coronavirus may pose particular risks to the heart because of how the virus gets into cells. To invade a cell, SARS-CoV-2 latches onto a protein called angiotensin-converting enzyme 2, or ACE2. This protein is found on cells in the lungs. This gives the virus access to these cells, where it can cause lung problems. But ACE2 also sits on heart-muscle cells and cells that line the blood vessels.

The virus’s interaction with ACE2 suggests that COVID-19 may damage the heart directly. At least that was the conclusion of researchers who wrote a March 5 commentary in Nature Reviews Cardiology. According to studies out of Wuhan, China, where the outbreak started, heart tissue in some people with COVID-19 died for reasons other than a heart attack.

Among one group of 416 patients hospitalized in Wuhan with the illness, one in five showed signs of heart damage. That finding comes from another research team. It shared its findings March 25 in JAMA Cardiology. This complication increased the risk of death for the patients: Half of those with heart damage died compared with only 4.5 percent of the other hospitalized COVID-19 patients, the study reported.

Finally, all infections can place an undue burden on a heart that’s already struggling with cardiovascular disease. Lung infections can “increase the workload that the heart is under,” says Scott Solomon. He’s a cardiologist at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School in Boston, Mass. “That means that your heart’s going to need more oxygen.” As flu and COVID-19 can interfere with the lung’s ability to deliver oxygen, “that can put an additional strain on the heart,” he says.

How long does it take for symptoms to show up?

The time it takes for symptoms to show up is estimated to usually be around four to five days. But it may be as short as two and as long as 14 days. This delay is known as the “incubation period.” Older people may have a slightly longer incubation period. One preliminary study found that people over 40 show symptoms after six days. In contrast, younger people may show symptoms after just four days. These data were posted February 29 on medRxiv.org.

How long are people contagious?

Researchers are starting to get hints of just when patients are most contagious. Infected people may shed infectious virus both before and after they have symptoms. That’s according to one study posted March 8 at medRxiv.org. It describes nine people who contracted the virus in Germany. This study finds that people are mainly contagious before they have symptoms and in the first week after showing signs of disease.

Patients produced thousands to millions of viruses in their noses and throats, about 1,000 times as much virus as was produced in SARS patients, Clemens Wendtner directs infectious disease and tropical medicine at Munich Clinic Schwabing. It’s a teaching hospital. There, he and his colleagues found that a heavy load of viruses may help explain why the new coronavirus is so infectious.

Scientists identified these nine people after they had been exposed to the virus. So they don’t know for sure when exactly people begin giving off the virus.

After the eighth day of symptoms, the researchers could still detect the virus’s genetic material, called RNA, in patients’ swabs or samples. At that point, however, they could no longer find infectious viruses. That’s an indication that antibodies made by the body’s immune system are killing viruses that get out of a patient’s cells, Wendtner says.

How does the disease spread?

Coronaviruses like SARS and MERS — and now SARS-CoV-2 — probably spread between people in ways similar to other respiratory diseases, says the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Germy droplets from an infected person’s cough or sneeze can infect someone standing almost two meters (6.6 feet) away.

On April 2, researchers said that the virus may also spread through the air in tiny particles that infected people exhale during normal breathing and speech. If the coronavirus is airborne, that could help explain why it is so contagious, and can spread before people have symptoms.

Touching surfaces covered with droplets and then touching your face can also spread the virus. New research suggests that this virus remains viable longest on plastic and stainless steel. There it can be detected for two to three days, although infectivity drops substantially after 48 hours. That’s according to a study posted March 9 at medRxiv.org and later published in NEJM. On cardboard, the virus lasts for 24 hours. “Live” virus also lasted three hours or more in the air. So even walking through a room where someone had coughed may pose the risk of infection, these data suggest.

Can people who have had the virus be reinfected?

Not likely, experts say.

There have been some reports of patients testing positive for the virus after they have recovered. They may even appear to get sick again. It’s likely, however, that the virus survived in the body longer than expected. Or people who appeared to recover just got worse after seeming to be on track for recovering. These results could also reflect issues with the current diagnostic tests, which aren’t sensitive enough to always pick up low levels of virus in an infected person.

“I don’t think that reinfection is that likely,” says Angela Rasmussen. She’s a virologist at Columbia University in New York City. But studying the disease in other animals, such as mice or nonhuman primates, could help determine whether the virus can lead to reinfections, she says.

One small study in rhesus macaques found that the animals couldn’t be reinfected with the coronavirus, at least in the short term. Those findings come from a report posted March 14 at bioRxiv.org. The monkeys developed antibody responses against the virus. That is what likely protected them from getting infected when they were exposed again 28 days after their first exposure. It’s still unclear, however, how long immune responses against the virus last.

Is the virus spread by people with no symptoms?

Unlike SARS and MERS, there now is ample evidence that people showing no symptoms — or very mild ones — can spread the new virus. Symptom-free spread is common for a number of contagious viruses. These include influenza and measles. This trait is something new, however, for the types of coronaviruses that cause epidemics.

How big of a problem is symptom-free spread?

Right now, no one knows. Researchers would need to understand how many people, in total, have been infected. To learn this, they need a test to identify people who have developed antibodies against the virus. That would confirm they had been infected, even if their body had cleared out the virus. So far only Singapore has done such tests.

But mild cases of COVID-19 that go unrecognized are fueling the coronavirus pandemic. That’s the finding of a study in Science based on data from the early days of the outbreak in China. Undocumented cases — those in people with mild or no symptoms — accounted for almost nine in every 10 infections. The good news: Those undetected cases were apparently only half as infectious as known cases. Symptom-free spread could make the epidemic very hard to control because such patients can spread disease with no signs that they’re sick.

How far has the disease spread?

As of April 3, more than 1 million people worldwide had been confirmed to have come down with COVID-19. At that time, nearly one-fourth of those cases were in the United States, according to tracking by Johns Hopkins University. More than 55,000 people had already died worldwide. More than 220,000 people had recovered from the virus.

The virus has now spread to at least 181 countries and territories.

By March 30, the number of cases reported in Wuhan, China, where the pandemic got its start had dropped to basically zero. European countries have suffered greatly, with Italy and Spain now accounting for nearly half of the roughly 54,000 global deaths.

On March 11, the World Health Organization labeled COVID-19 a pandemic. A pandemic usually is defined as the worldwide spread of a new disease. Once an epidemic spreads to two or more continents — and shows sustained, person-to-person transmission — it’s called a pandemic.

How many undetected cases are out there?

No one knows for sure. One reason: There aren’t enough test kits to test everyone who might be infected. Another reason is that people may be infected with the virus but show no symptoms or very mild ones. Those people may, however, still be able to infect others.

What’s the situation in the United States?

As of April 3, U.S. health officials have confirmed the new coronavirus in more than 213,000 people across all 50 states and territories, with more than 4,500 deaths.

Officials announced the first COVID-19 case in the United States linked to travel on January 21. On February 26 and 28, U.S. health officials reported two women in California had been infected. What was special here: Neither woman had traveled to affected areas nor been exposed to someone known to have the disease. Such cases are examples of what is known as “community spread” of an infection. Officials have since identified a growing number of community-spread cases throughout the nation.

In the wake of steadily rising numbers of COVID-19 cases, health officials have put in place new “social distancing” measures. These include advising people to avoid gatherings of more than a few people, at least through at least the end of April. Most states have shut down bars, dine-in restaurants and other non-essential businesses. As of April 2, the New York Times reported, at least 297 million people in at least 38 states, 48 counties, 14 cities, Washington, D.C., and Puerto Rico were encouraged to stay home.

What can I do to prepare?

Practicing good hygiene is the most important way to protect yourself. Tips from the infectious disease experts include washing hands with soap and water or using alcohol-based sanitizers. We have published a top 10 list of these tips. If you think you are sick, stay home and avoid traveling.

The CDC also recommends having a plan in place for how you and your family will get by if and when all or part of your family must stay home from work or school.

Does hand sanitizer actually work?

Although washing your hands with soap and water is best, hand sanitizers also work.

When a single virus leaves an infected cell, it takes part of that cell’s membrane with it. This membrane forms a protective envelope around the virus. The alcohol in hand sanitizer can disrupt this envelope. That essentially “kills” the virus.

Why are masks now being recommended for the public?

On April 2, the White House said it would soon release recommendations on whether people should wear cloth masks, even if they have no symptoms. Health officials in the United States and Europe had initially recommended that only people with COVID-19 symptoms (and those caring for them) should wear masks. The reason: a fear of shortages for health care workers.

Much of Asia, however, recommended wearing the masks. So have an increasing number of U.S. states and health experts.

It’s important to remember that these masks are not meant to be a replacement for social distancing. And the masks are designed to protect others from the mask wearer, not the other way around. That’s because surgical masks are designed to keep germs in, not keep them out.

If a sick person wears a surgical mask, the fabric will catch germy droplets of spit or nasal mucus. That can prevent the virus from getting onto surfaces that other people might touch. Studies indicate that a large share of infections from the novel coronavirus come from people who showed no symptoms. So their wearing even fabric surgical masks might limit some spread of the virus by these people.

Without a mask, such infected people can likely spread the new coronavirus even without coughing or sneezing. That was the conclusion of a research committee of the U.S. National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine. In March 2020 it reviewed data on the ability of sick people to spread virus particles in the air. Any such small particles in the air are known as aerosols.

Data on the SARS-CoV-2 germ is limited, noted that committee in an April 1 letter by its chairman. Still, it found data on other viruses, including other coronaviruses. And those showed that virus aerosols can be released by normal breathing. As such, the letter said, it is possible that viruses such as SARS-CoV-2 could be spread just by conversation.

That letter did not address the issue of masks. An April 3 report in Nature Medicine did. An international research group led by a team at the University of Hong Kong studied 246 people sick with viral infections. Some had coronaviruses (which cause the common cold). Others had influenza viruses or rhinoviruses (which also cause the common cold). A few were infected by at least two different types of virus.

The researchers randomly assigned half of the people to wear cloth surgical masks. Then the team measured viruses present in each person’s exhaled breaths. Between 30 and 40 percent of the people with coronavirus infections exhaled viruses if they wore no mask. But no virus was detected in breaths exhaled through a cloth mask. Cloth masks appeared just a bit less protective for people with the flu. And the masks made no difference in how much virus was exhaled by people with rhinovirus infections.

The best masks to guard against such airborne viruses are known as N95 masks. These are what hospital workers use around people who may be sick. They are different from the thin, cloth masks that doctors and nurses wear in surgery. In early 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic led to a worldwide shortage of N95 masks. That’s why the medical community has been asking the public not to buy or hoard N95’s: They should be saved for hospital teams and first responders.

Growing concern over how to slow the spread of the new virus led many people to ask whether homemade fabric masks would offer at least a little help for the public. And by April 2, a consensus was growing that even homemade cloth masks could be helpful. Surely, they would be better than nothing, says David Witt. He’s an infectious-disease expert and epidemiologist. He works at Kaiser Permanente Oakland Medical Center in California.

One 2008 study of homemade cloth masks worn by members of the general public was published in PLOS ONE. It found that although not as useful as N95’s, homemade masks can offer some protection against viral particles.

Such a cloth mask must filter out small particles but still be easy to breathe through. Some materials, such as vacuum bags, filter well, but make breathing difficult, a 2013 study showed. Cotton T-shirts offer a breathable fabric that in this study filtered microbes roughly half as well as surgical masks.

One additional advantage of wearing even these masks: They reminded wearers that they should not be touching their nose or mouth (which were now covered).

Such masks don’t fit perfectly around the face. This leaves gaps on the sides. Many people also don’t wear them properly (such as leaving their noses exposed while covering their mouth). That’s why JAMA Network published a whole webpage for the public on March 4 showing how masks should — and should not — be used during an epidemic such as COVID-19.

What should I do if I think I have COVID-19?

If you have a fever and respiratory symptoms, call your medical provider ahead of time, says Malani, the infectious-disease expert. Let them guide you on what step to take next.

Local health departments, with help from doctors, have been asked to figure out whether someone should be tested for coronavirus.

It’s important to remember that for most people, the risk of getting severely ill appears to be fairly low. But even if you face a low risk of severe disease, if you do become ill, you risk spreading COVID-19 to someone at high risk of serious illness.

How do doctors test for the virus?

The World Health Organization suggests that doctors take multiple samples for testing. These should include swabs of the nose and throat together with blood and with phlegm from the lower respiratory tract.

In the lab, researchers look for genetic evidence of the virus. They do this using a technique called RT-PCR. (That’s short for reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction.) If virus is found, the technique will make copies of its RNA — the virus’s genetic code — that is unique to SARS-like coronaviruses. Where the tests come back positive, researchers will do more analyses to pin down whether SARS-CoV-2 was the virus present. The method relies on patients being sick enough that they had high amounts of the virus at the time of collection. So not everyone who is infected will have a positive test.

The first CDC diagnostic kits for SARS-CoV-2 had been flawed. That limited the screening of patients by local and state labs. As of March 3, federal officials said they expected within a few days the United States would have the capacity to run some one million tests. In fact, by March 13, the U.S. total was only around 14,000, according to the CDC.

Where did the virus come from?

Coronaviruses are zoonotic. That means they had been in animals and then leaped to people. Such diseases may reach people when those animals are handled, kept as pets or prepared to be eaten. In the case of SARS-CoV-2, experts suspect bush meat — wild animals eaten as human food — may be the initial source.

Current data suggest that the virus made the leap from animals to people just once. Since then, it has been spreading from person to person.

Bats are known to host many coronaviruses. In most cases, however, they don’t pass the virus directly on to people. SARS probably first jumped from bats into raccoon dogs or palm civets before making the leap to humans. (People in Asia sometimes eat civets, bats and other animals.) MERS went from bats to camels before leaping to humans.

A paper published January 22 in the Journal of Medical Virology suggests that parts of the new coronavirus appear to have come from bat coronaviruses — but that snakes then may have passed the virus to people. Many virologists, however, doubt are skeptical of that. Other analyses have proposed that unusual mammals known as pangolins might be the source.

Studies have shown pangolins can host coronaviruses. However, those viruses are different enough from SARS-CoV-2 to hint that pangolins are not directly responsible for being a source of COVID-19 illness in people.

Why does knowing the virus’s origin matter?

Pinpointing the source of the virus is a step toward protecting people from coming into contact with more infected animals, and possibly starting another outbreak.

Can pets get sick?

A cat in Belgium seems to have become infected with the coronavirus and may have had COVID-19. The case — the first reported in cats — suggests that the animals can catch the virus. For now, there still is no evidence that cats play a role in spreading the new coronavirus. It also is not yet clear how susceptible these animals are to the disease.

The cat probably picked up the virus from its owner. That person fell ill with COVID-19 after traveling to northern Italy. About a week later, the cat became ill. It had trouble breathing, vomited and had diarrhea. In lab tests, its poop and vomit showed high levels of SARS-CoV-2’s genetic material. But there was some question of whether the sick owner could have contaminated those samples that were tested.

In 2003, researchers reported in Nature that cats could be infected with the SARS virus and transmit it to other cats in the same cage. None of the cats showed any symptoms. The same was true for ferrets, although the ferrets did become sick.

At the present time, COVID-19 cases in pets appear to be extremely rare. If COVID-19 were a serious problem for pets, we likely would know it by now, says Jane Sykes. “Dogs and cats may be what we call dead-end hosts,” says this veterinarian at the University of California, Davis. “They get infected with the virus. They shed it. But they’re unlikely to shed it enough to spread it to people.”

If owners test positive for COVID-19, they should consider having someone else in the home care for the pet while they’re sick. Or they might want to wear a mask around the pet and limit contact with their animal.

When will it end?

That’s a tough question, experts say.

Keeping schools closed and encouraging people to generally stay home could suppress the pandemic after five months, according to a March 16 report from Imperial College London in England. But once such restrictions are lifted the virus would likely come roaring back. Until a vaccine becomes available, potentially in 12 to 18 months, the report argues that major, society-wide social distancing measures are necessary.

Other experts say that social distancing might not need to last nearly that long. It might need to last only a few months. We could get a big break if the virus’ spread slows with warmer weather, though so far there’s no indication that will happen.

“That would be a great stroke of luck,” says Maciej Boni, and might allow more people to return to work once the number of new cases begins to fall. Boni is an epidemiologist at Penn State University.

It’s possible that the virus could begin circulating permanently in humans, like influenza or common colds. It’s not yet known, however, if the virus might become seasonal, like the flu.

Erin Garcia de Jesus, Tina Hesman Saey, Aimee Cunningham, Jonathan Lambert, Helen Thompson and Janet Raloff contributed to reporting of this story.