Warmer seas trigger skyrocketing ice loss in 3 Antarctic glaciers

Powerful ocean waves battering sea ice helped spur the rapid retreat

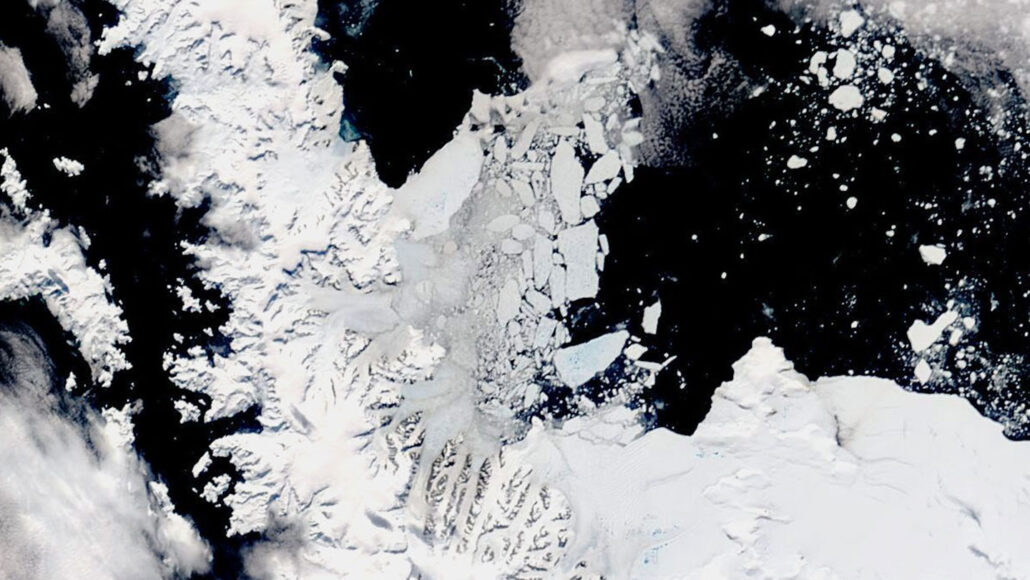

This 2022 satellite photo shows a breakup of sea ice along the Antarctic Peninsula. This has triggered a rapid retreat, here, of three glaciers that flow into the sea.

Joshua Stevens, MODIS/LANCE/EOSDIS/NASA, WORLDVIEW/GIBS/NASA

By Douglas Fox

SAN FRANCISCO, Calif. — Several glaciers in Antarctica are undergoing dramatic ice loss as they accelerate into the sea. Hektoria Glacier is retreating fastest. Its sliding speed has quadrupled in just 16 months. As a result, scientists report, it’s lost 25 kilometers (15.5 miles) of ice off its front.

Such a rapid retreat “is really unheard of,” says Mathieu Morlighem. He did not take part in the new work. But he knows about such issues. He’s a glaciologist at Dartmouth College in Hanover, N.H.

Unusually warm ocean temperatures have triggered these glacial retreats. They’ve allowed a series of large waves to hit a section of the coast that normally is shielded from them.

“What we’re seeing here is an indication of what could happen elsewhere” in Antarctica, says Naomi Ochwat. She’s a glaciologist at the University of Colorado Boulder. She presented her team’s new data December 11, here, at the American Geophysical Union annual meeting.

The role of the Larsen B Ice Shelf

Hektoria Glacier, Green Glacier and Crane Glacier sit near the tip of the Antarctic Peninsula. This is where the continent reaches up toward South America. Larsen B Embayment is an inlet on the peninsula. It’s shaped like a crescent moon. As the three glaciers ooze off its coastline, their ice merges.

This used to create a huge floating slab known as the Larsen B Ice Shelf. About the size of Rhode Island, it was some 200 meters (655 feet) thick. It filled the entire bay. This stabilized the glaciers flowing into it. Having existed for more than 10,000 years, it had once seemed stable.

But during a warm summer in 2002, the shelf suddenly fragmented into thousands of skinny icebergs. The Hektoria, Green and Crane glaciers were no longer held in place by the ice shelf. Suddenly, they began to flow into the ocean several times faster than they had before.

This shed billions of tons of ice over the next decade.

Normally, a thin veneer of sea ice forms over the bay each winter. It would melt again in summer. But in 2011, the sea ice began to persist year-round, helped by a series of cold summers. This began to slow the recent speedy loss of glacial ice here. Attached firmly to the coastline, this “landfast ice” grew between five and 10 meters (16.5 and 33 feet) thick. This again stabilized the glaciers. Again, their floating tongues started to advance back into the bay.

But that changed abruptly in early 2022. On January 19 and 20, the landfast ice disintegrated into fragments. And these drifted away.

To find out what happened, Ochwat’s team turned to data from ocean buoys farther north. These showed that powerful waves had swept in. They cracked apart that landfast ice.

Glacial retreats accelerate

The Southern Ocean encircles Antarctica. It holds some of the world’s roughest seas. The Antarctic Peninsula extends into this turbulent zone. But its east side, where the Larsen B Embayment sits, rarely feels heavy waves. Several hundred kilometers (miles) of pack ice — floes of sea ice, pressed together by ocean currents — normally dampen the waves. As a result, waters near Larsen are usually as flat as a mirror.

But in 2022, water temperatures near the surface of the Southern Ocean rose several tenths of a degree higher than normal. This caused the pack ice to shrink and peel away from the peninsula. That exposed this area to waves. Some that were more than 1.5 meters (5 feet) high slammed into the area.

Those waves broke up the landfast sea ice. The glaciers now sped up as their floating tongues — no longer held in place — fragmented into bergs.

Crane Glacier lost 11 kilometers (6.8 miles) of ice. This nearly erased its floating tongue. Green Glacier lost 18 kilometers (11.2 miles), encompassing all of its floating ice.

Hektoria lost all 15 kilometers of its floating ice — followed by another 10 kilometers that is normally more stable (because this ice rested on the seafloor). Hektoria’s loss of 300 square kilometers (116 square miles) of ice has been “faster than any tidewater glacier retreat that we know of,” Ochwat says. A tidewater glacier is one that slides into the ocean, resting on the seafloor, without any floating ice at its front.

The previous standout retreat had been at Alaska’s Columbia Glacier. It lost 20 kilometers of ice, records show — but over 30 years. Hektoria lost its 10 kilometers of nonfloating ice in just five months. That included 2.5 kilometers that crumbled in just one 3-day period!

All of this suggests that people trying to predict sea-level rise need to consider sea ice, says Morlighem at Dartmouth. Until now, “its role in [glacier] dynamics has been completely ignored.”

Ochwat is waiting to see what will happen as the current Antarctic summer warms from December to March. Hektoria and the other glaciers have been retreating only during summer months, when sea ice is absent. They’ve paused over winter, when the surface of the bay freezes for a few months.

If Antarctic sea ice continues to shrink, as it has since 2022, this could spell big trouble, says study coauthor Ted Scambos. He, too, is a glaciologist at the University of Colorado Boulder. “You’re going to have a longer section of coastline where wave action can act on the front of ice shelves and glaciers.” If that happens, glacial retreat could speed up even faster. And that could boost the rate at which sea levels rise across the planet.