Antibodies from former COVID-19 patients could become a medicine

Extracted from blood plasma, these antibodies can be used to possibly prevent or treat disease in others

Blood plasma, the yellowish liquid in this test tube, is the portion that contains antibodies. Plasma with antibodies from people who recovered from coronavirus infection, is being tested as a way to prevent or treat COVID-19 in others.

Johnce/iStock/Getty Images Plus

SEPTEMBER 9, 2021 UPDATE: As the story below noted, “Convalescent plasma is an experimental therapy for COVID-19. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration, or FDA, recently authorized it for emergency use.” But on August 18, 2021, the National Institutes of Health reported disappointing findings from a trial that it had helped fund. “We were hoping that the use of COVID-19 convalescent plasma would achieve at least a 10 percent reduction in disease progression [for recently infected, high-risk patients],” said Clifton Callaway. He’s a doctor who led the trial. “Instead, the reduction we observed was less than 2 percent,” said Callaway, who works at the University of Pittsburgh in Pennsylvania. He told the NIH that “We wanted this to make a big difference in reducing severe illness and it did not.” So the trial ended after just six months. However, NIH adds, other studies of COVID-19 convalescent plasma are ongoing or planned in different populations. So it’s possible that conclusions about the treatment’s promise might still change. — Janet Raloff, Editor

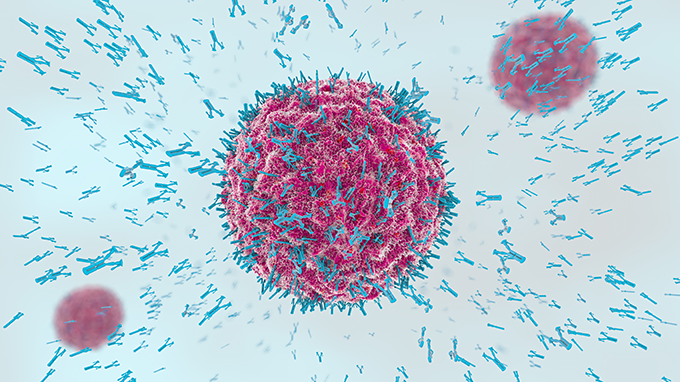

Since late March, some U.S. patients have received a promising experimental treatment for the new coronavirus. All were critically ill and in hospitals. They didn’t get a new drug. Instead, doctors infused their blood with antibodies. These immune proteins were taken from the blood of people who had already recovered from COVID-19.

The treatment is known as convalescent (Kon-vuh-LES-sunt) plasma. Plasma is a yellowish liquid in blood. It carries antibodies. The body’s immune system makes those antibodies — special proteins — in response to a virus or vaccine. Those proteins can bind to a virus and help to remove the infectious particles.

It takes time for the body to make antibodies, around a week or two. But once they are available, the immune system can quickly respond to a particular virus the next time it confronts it. Antibodies are part of what is known as the body’s “active immunity.” For some viruses and vaccines, active immunity can last decades — even the rest of your life.

In contrast, the new plasma therapy uses someone else’s antibodies to fight infection. The immunity it offers may last for only weeks to a few months. But it’s just possible that these proteins can “prevent infection or treat infection in another patient,” says Jeffrey Henderson. He’s an infectious disease physician and scientist who works at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis, Mo.

Convalescent plasma is an experimental therapy for COVID-19. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration, or FDA, recently authorized it for emergency use. How well it will work remains unknown. But with the United States now leading the world in confirmed cases of COVID-19 — and no proven treatments known — researchers are racing to set up clinical trials to test convalescent plasma.

If the therapy works, FDA might approve its wider use to treat infections with SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19.

A vaccine is still needed to protect people from the infection. But such a vaccine for SARS-CoV-2 is at least a year away or more. Until then, scientists are searching for ways to treat the infection. Donated antibodies is one such treatment, notes John Roback. He’s a pathologist at Emory University School of Medicine in Atlanta, Ga. There, he performs research on blood-transfusion medicine.

Setting up clinical trials

Henderson, in St. Louis, is part of a group of U.S. researchers working to set up clinical trials for convalescent plasma. That group is known as the National COVID-19 Convalescent Plasma Project. It plans to test the antibodies in three different groups.

One would test whether they can prevent infection in people exposed to COVID-19 by a family member or other close contact. This trial would test plasma from COVID-19 survivors against a placebo, explains project member Shmuel Shoham. He’s a doctor at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, in Baltimore, Md. There, he specializes in infectious diseases. That placebo treatment would be plasma taken from patients prior to December 2019. That was before the viral epidemic reached the United States. This plasma, therefore, would have no COVID-19 antibodies.

A second trial plans to test whether antibodies can help people with moderate disease who are in the hospital. It would study whether it could keep them from needing intensive care, Shoham says. A third trial aims to study whether the therapy helps the illest of patients.

While using donated antibodies to fight COVID-19 is new, this type of treatment is not. An April 1 commentary in the Journal of Clinical Investigation describes many instances in which donated plasma appeared to prevent or fight infections.

It was used to help stop outbreaks of measles and mumps. This was before vaccines for them were available. And there’s some evidence that people who got such plasma during the notorious 1918 flu pandemic were less likely to die.

There’s even been a few tests of COVID-19 antibodies from recovered patients to treat critically ill patients in China. But in those tests, the treatment was not compared to a placebo. Such placebo-controlled trials are the gold standard for evaluating how well a medical treatment works.

Plasma questions

In the United States, some blood banks and hospitals are gearing up to collect plasma from people who got over COVID-19. The Red Cross has set up a form for people who would like to donate. The National COVID-19 Convalescent Plasma Project also has info on how to register to donate plasma.

For the U.S. trials, the researchers will study the donated plasma. They want to know if it has what’s known as “neutralizing” antibodies. Such antibodies prevent a virus from entering a host cell. That would stop an infection.

Researchers suspect that this type of antibody is what makes plasma therapy effective. It also hints at when using the plasma would help most.

Early in the disease, the virus infects cells to copy itself. “But as the disease progresses, the tissue damage done by the virus is more difficult to reverse,” says Henderson. Inflammation — not the virus itself — can cause damage as the infection now continues. Still, he says, antibody therapy might be able to help someone who is critically ill.

As doctors await answers from completed trials in the United States and other countries, more U.S. patients may receive the experimental treatment. It’s great that critically ill patients might have this option, Shoham says. In the meantime, “we’re trying to … find out if [convalescent plasma] actually works.”