Are you scared of heights? Virtual reality could help

In a therapy app, an avatar coaches people through sky-high situations

In a new virtual reality therapy app, an animated coach guides people with a fear of heights through activities such as saving a cat from a tree.

Oxford VR

In the future, therapy patients may spend less time sitting in a therapist’s office and more time exploring virtual worlds.

Researchers have created a new virtual reality (VR) app to treat the fear of heights. The app just had a clinical trial. And the treatment seemed to work. Participants reported being much less afraid after using the program for just two weeks.

People have developed other VR therapies in the past. These programs needed a real-life therapist to guide patients through the treatment. But the new system only uses an animated avatar within the app. The avatar coaches patients as they climb a virtual high-rise. This kind of therapist-free counseling could make it much easier for people to get help for fears and other disorders. The researchers described their results online July 11 in the Lancet Psychiatry.

This is “a huge step forward” for VR therapy, says Jennifer Hames. She’s a clinical psychologist at the University of Notre Dame in Indiana who wasn’t involved in the work. With this system, people don’t need to visit a therapist’s office to get expert help. They could get help in their regular doctor’s office, or even at home. That could be good for people who aren’t comfortable with face-to-face therapy, or who can’t afford it, she says.

People use the app with a VR headset, handheld controllers and headphones. In the virtual world, an animated character guides the user through a 10-story building. The upper floors overlook a ground-level atrium. On every floor, the user performs tasks to test their fear responses. The tasks also help them learn that they’re safer than they might think.

These activities start out relatively easy, such as standing near a dropoff where a safety barrier gradually lowers. Then the challenges get harder, such as riding a moving platform out into the open space over the atrium.

By working through these activities, “the person builds up memories that being around heights is safe,” says Daniel Freeman. This counteracts their fears, he says. Freeman is a clinical psychologist at the University of Oxford in England.

On the edge

To test their app, Freeman and colleagues recruited 100 adult volunteers. All the volunteers were moderately to severely afraid of heights. The researchers randomly assigned 49 people to have VR treatment. That meant using the program for about six 30-minute sessions over two weeks. The other 51 participants got no treatment.

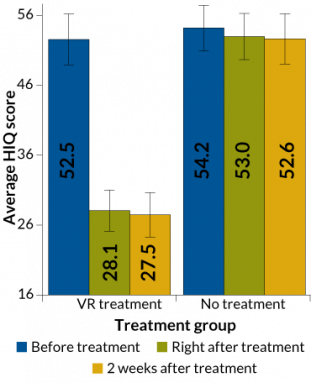

Before the experiment began, participants filled out a questionnaire that rated their fear of heights from 16 to 80. A score of 80 was the most severe. They filled out the same questionnaire right after the treatment. Then they did it again two weeks later.

The scores of patients who got no treatment stayed the same. But people who used the VR app dropped an average of about 25 points on the scale. Also, after using the app, participants “could go to places that they wouldn’t have imagined possible,” Freeman says. Those places included steep mountains, rope bridges or simply escalators in shopping malls.

“When I’ve always got anxious about an edge, I could feel the adrenaline in my legs, that fight/flight thing; that’s not happening as much now,” one participant said. “I’m still getting a bit of a reaction to it, both in VR and outside as well, but it’s much more brief, and I can then feel my thighs soften up as I’m not bracing up against that edge.”

The results give strong evidence that the new VR program is more helpful than no treatment at all. But researchers still need to study how VR therapy compares to sessions with a therapist, Hames says. And Freeman’s team only studied participants for a couple of weeks after their treatment. So they know don’t how long the effects of this therapy last. (Previous research on VR treatment led by a therapist has found that improvements lasted for at least a year.)

Fully automated VR therapy may be good news for people who fear heights. But it’s not clear how well this type of system could work for more complex mental health issues, says Mark Hayward. He’s a clinical psychologist at the University of Sussex in England. Hayward wrote a commentary on the study that appears in the same issue of the Lancet Psychiatry.

Virtual reality may be good for helping people who fear everyday situations, Hayward says. That includes people who have common phobias, social anxiety or paranoia. But when it comes to helping people with more severe symptoms, VR probably won’t replace trained therapists any time soon.

“We can’t get carried away and say we can automate all [mental health] treatment,” says Albert Rizzo. He develops virtual reality therapies at the University of Southern California in Playa Vista. Rizzo wasn’t involved in the new work. But he says the new therapist-free system for helping fear of heights is “an excellent first effort.”