New training builds ‘mental’ muscles in athletes

It builds focus and resiliency so that competitors can reliably perform their best

U.S. figure skater Nathan Chen, seen preparing for the 2022 Winter Olympics in Beijing. After learning in 2021 that some elite athletes had withdrawn from some competitions to work on their mental health, he offered his support. People must realize, he said, “We are important as people, not just athletes.”

LOIC VENANCE/AFP VIA GETTY IMAGES

BELIEVE. That’s what a sign says that hangs above Tommy Minkler’s office door at West Virginia University. The blue letters on this yellow poster board give a nod to the Emmy-winning TV show Ted Lasso. It’s also a reminder to trust in the work this mindfulness researcher is doing to help elite athletes.

In the show, Lasso is an American football coach who is recruited to head an English football team. His experience with American football leaves Lasso utterly unprepared to coach soccer. So he relies on his positive attitude and folksy charm to bond with his new players. On his first day, Lasso posts the BELIEVE sign above his office door. Later, the team often rallies around that sign just before hitting the field.

But belief alone can’t get athletes to the goal when they run into mental speed bumps — or full-on roadblocks — in training and competition. Lasso’s striker, for instance, needed a therapist when he suddenly found himself unable to nail his usually flawless penalty kicks. In real life, U.S. gymnast Simone Biles developed the twisties at the Summer Olympics in 2021. Her mental block was petrifying; one wrong move on the uneven bars or a failed flip on the balance beam could be paralyzing, even fatal. Her decision to withdraw from five of six event finals after years of intense training shocked nearly everyone.

The public expects these elite athletes to be unflappable.

Admitting they’re not is “fundamentally at odds with being a competitor,” said retired figure skater Sasha Cohen in the 2020 HBO documentary, The Weight of Gold. Cohen was a U.S. silver medalist at the 2006 Winter Olympics. When competing at the elite level, she said, “You need to show the world you are strong. You need to show your competitors you are strong.” To let people know you have mental-health issues, she said, “just cracks the facade” that you are a fearsome champion.

In society, those cracks are often seen as weakness. It’s a faulty perception. But it can keep athletes from talking about their problems.

Reactions to Biles’ decision, last summer, make clear that a stigma still exists. She faced backlash after withdrawing from several Olympics events. So did Japanese tennis star Naomi Osaka, when she pulled out of the 2021 French Open to focus on her mental health.

But Biles and Osaka had some supporters. These included fellow athletes who were inspired by these choices. “I didn’t even know that was an option,” said U.S. figure skater Nathan Chen at a news briefing last October.

Just because elite athletes are physically fit does not guarantee mental fitness. The International Olympic Committee and other sports groups have recently begun to acknowledge the importance of mental health in athletes. There’s also been an explosion of research in the last few years on the mental health of elite athletes, notes Carolina Lundqvist. She’s a psychologist at Linköping University in Sweden. She points to one 2020 analysis in the International Review of Sport and Exercise Psychology. It identified two promising mental-health tools.

One is mindfulness. It refers to paying attention to — or staying in — the present moment. The other, called ACT, is short for acceptance and commitment therapy. Together, they can train people to accept difficult thoughts or feelings rather than actively work to shed them. Studies are showing these tools can boost athletic performance. More importantly, they can lead to richer personal experiences.

Athletes “are human beings first,” notes Minkler. Their lives are not all about winning medals or championships. Mindfulness and ACT help athletes “engage differently with their thoughts and emotions,” he says. That can leave them healthier and more content.

A sizeable problem

Athletes can be reluctant to report mental health problems because of stigma. Data in this table come from a 2019 consensus statement from the International Olympic Committee. They show information on mental health disorders in elite athletes were limited, but depression and anxiety rates appeared similar to the general public’s. Eating disorder rates were higher in athletes.

Prevalence of mental health issues in elite athletes

| Disorder | Prevalence |

| Depressive symptoms | 4–68% |

| Generalized anxiety disorder, self-reported | 14.6% |

| Eating disorders | 0–19% in men 6–45% in women |

Team tests

Women toss the ball with an intense focus. They’re running drills on a lacrosse field at Marymount University in Arlington, Va. This practice might seem routine. But these players are paying extra attention as a result of some experiments they’ve taken part in during the last few years. Minkler, a former lacrosse coach, has been working with them. So has psychologist Tim Pineau.

The researchers wanted to know if mindfulness training would improve the players’ performance and sense of well-being. With buy-in from the school’s athletic director and lacrosse coach, Pineau led the players through six weeks of mindfulness training prior to one season’s play. They then had monthly follow-ups over several more seasons.

They started with stationary meditations. These focused on breathing and self-compassion. Then they moved on to mindful yoga and walking. They ended with throwing and catching exercises. In groups, these players also talked about what they’d learned. They described how they used this new training to let go of mistakes.

Their coach reported that the players who took part seemed more focused on the second-to-second decisions of a game. They no longer dwelled on things that had gone wrong.

In surveys, players later reported feeling that after the mindfulness training, they could more easily totally immerse themselves in the game. This is often described as “being in the zone.” They also reported feeling less anxious, the researchers wrote in 2019 in the Journal of Sport Psychology in Action. Before training, the team had four wins and 15 losses. In the season after the training, the team won more games than they lost. They even qualified for the regional championship. The next year, the team won their regional championship.

The findings reinforce results from a study in Florida with the University of Miami football team, the Hurricanes. Amishi Jha is a neuroscientist at the university. She teamed up with Hurricanes head coach, Al Golden, and his players to track how well the team paid attention during preseason training.

In the lab, the researchers measured the players’ focus by having them hit the spacebar on a keyboard when they saw certain numbers on a computer screen, such as 2 or 4. Players were told not to hit the bar when they saw other numbers, such as 3. The stronger their attention, the better players were at not hitting the spacebar when 3’s flashed across the screen.

After measuring the players’ baseline attention, the researchers divided the players into two groups. One worked through a four-week training with mindfulness meditations. The other received four weeks of relaxation exercises. Mindfulness exercises focused on bringing attention back to the present moment whenever the mind strayed. Relaxation exercises focused on relieving tension, without focusing cues.

In earlier experiments, Jha had found that high stress, poor mood and perceived threats can disrupt focus in medical and military professionals. With the Miami players, she had them complete mindfulness or relaxation work during practice sessions before the season officially got underway. In these grueling physical workouts, coaches would decide who would get cut from the team.

When given the computer-attention test after the preseason training ended, the players didn’t focus as well as before. They also reported being more anxious, more depressed and less happy overall. Jha says this was a result of being stressed from the grueling physical workouts.

Although their focus declined in such a high-stress setting, the attention of players who regularly practiced mindfulness exercises dropped far less than those who regularly practiced relaxation exercises. Jha’s team shared its findings in the Journal of Cognitive Enhancement.

“Attention is the fuel for our ability to not just think and do cognitively demanding tasks, but to regulate our emotion and connect” with other people, Jha says. Protecting the ability to pay attention can protect mental health. It’s among lessons she describes in her 2021 book Peak Mind. It describes how to build mental “muscles” in as little as 12 minutes a day.

Practice boost

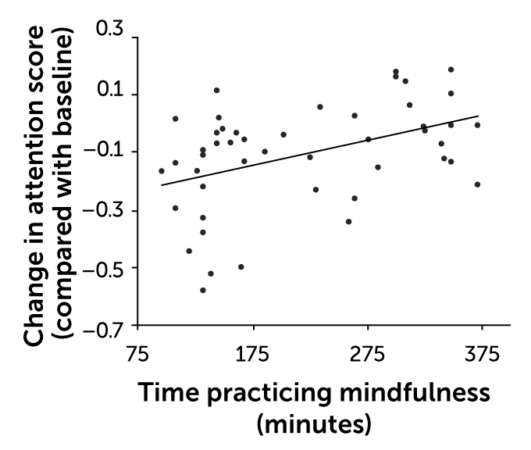

As this graph shows, the longer the University of Miami Hurricanes practiced mindfulness, the less their ability to pay attention dropped during a period of intense physical training.

Association of mindfulness practice time with attention in college football players

Mental discipline

Meditative trainings are like a push-up for the mind. “You have to work at it. You have to be disciplined,” says Minkler. “You wouldn’t go in the weight room and do five push-ups and say, “That’s it, that’s all I need to do.’” Similarly, he says, “You can’t meditate once for 10 minutes and say, ‘I’m mindful and in the present.’”

Graham Mertz is a quarterback at the University of Wisconsin–Madison. After what he felt was a disappointing 2020 season, Mertz began working with Chad McGehee. He’s the Wisconsin Badgers’ director of meditation training. There’s roughly 40 seconds between plays in a game. That training helped Mertz figure out how to reset himself mentally between offensive plays, he told the Wisconsin State Journal. Mertz says he has spent a lot of time learning how to put what’s just happened behind him.

The best approach he found was to take a deep breath, close his eyes and rub his fingertips together. The Badgers finished the 2021 season with eight wins and four losses, plus a win in December’s Las Vegas Bowl.

But mindfulness training doesn’t work the same way for everyone. Studies suggest that mindfulness exercises can distress some people by bringing up past trauma, Minkler says. Having therapists on hand to work with athletes who react to mindfulness training this way can be important.

No judgments

Acceptance and commitment therapy, or ACT, is another technique counselors are using to help athletes. The goal is to teach athletes to separate their competitor identity from their personal one.

ACT does not attempt to change negative thoughts, such as “I suck today.” Instead, it accepts such thoughts as being independent of who or how talented an athlete is. Now, rather than getting stuck in a downward spiral of doubt, an athlete can bring her focus back to the race or game at hand.

Eugene Koh Boon Yau is a psychiatrist at the University of Putra Malaysia in Seri Kembangan. Recently, he’s worked with three triathletes competing to represent Malaysia at international competitions. All three struggled with self-doubt. These athletes can spend up to 17 hours swimming, biking and running in a race. So letting go of the detrimental self-talk can be extremely important when a competitor moves in front or when an athlete is tired and just wants quit, Yau says.

Over six weeks, he walked each athlete through mindfulness training. Each learned to notice and label their thoughts and emotions, especially negative ones. They accepted those thoughts without judgment. Then each identified what he wanted to be remembered for, should his career end the next day. Yau and these athletes discussed how to use mindfulness and thought acceptance to stay focused during a race on their performance — not on what their competitors were doing.

The training “does help me with reducing anxiety and overthinking,” says Edwin Thiang. He’s a triathlete who worked with Yau. Thiang says he’s still surprised by how this training has calmed him down and helped him to focus, especially in races where the stakes were high.

Another triathlete who worked with Yau found it easier to accept thoughts of self-doubt when a competitor overtook him. Before the mental training, this athlete would slow down in such situations, giving up hope of finishing well. After the training, he identified his self-doubt as an emotion, not a reality. By shifting his attention back to the mechanics of either swimming, biking or running, he could keep the pace he set for himself during the race.

Yau and his colleagues reported their findings last May in the Journal of Sport Psychology in Action.

When paired with elements of ACT, mindfulness can quickly keep players moving and help them stay in the game — especially if they make a mistake, says Mike Gross. He’s a psychologist at Princeton University in New Jersey. “There’s less … of those mental gymnastics or the tug-of-war in the mind” that can mess up a player even more. In fact, he says, players trained with mindfulness and ACT were less likely to get extremely upset or sad than were players trained with traditional sports-psychology tools. They also were better able to cope with changes and to take creative approaches to tasks.

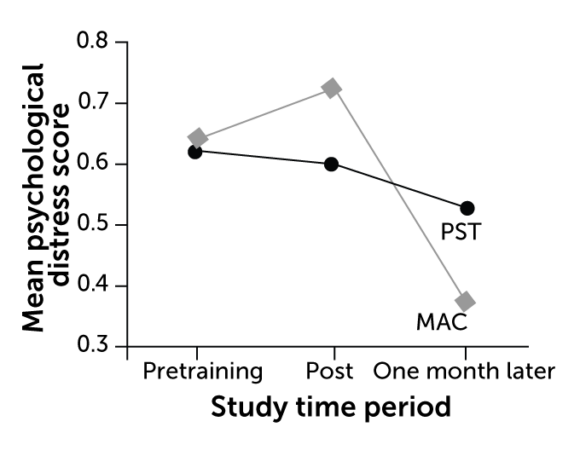

Drop in distress

This graph shows reported levels of behavioral difficulties and emotional distress among a group of female college basketball players. One month after players had training in a mindfulness-acceptance-commitment approach, or MAC, their problems had decreased compared to players receiving more traditional psychological training, or PST.

Influence of MAC versus PST on psychological distress in female college basketball players

In fact, Minkler argues, performance problems rarely have anything to do with technical skills. Mental hang-ups in training and competition often are related to interpersonal issues, like relationships with teammates, coaches or loved ones. Mindfulness and ACT can help athletes work through those issues to bring their focus back to their sport, he says.

Researchers using these techniques say they’ve seen similar off-the-field benefits in student athletes. This included improved focus on readings for classes and better communication with their friends and family.

With such results in mind, Jha say she’d like to test how mindfulness and ACT training might work for Olympic athletes. Ideally, she says, she would train Olympic coaches to work with their competitors. Then she’d track the athletes’ performance, mental health and attention. She says that kind of study is even more relevant after the very public experiences last summer of athletes such as Simone Biles and Naomi Osaka.

The public tends to view elite athletes as pillars of excellence. Yet many have been experiencing extreme challenges to their mental health, Jha says. “How do we have the mental fitness match the physical excellence?” Studies on mindfulness and ACT hint that matchup is achievable, she says, and the training might benefit not only elite athletes but all of us.