Babies prove sound learners

Scientists are gaining new insights into why babies are so good at learning languages.

By Emily Sohn

It can be hard to know what newborns want. They can’t talk, walk, or even point at what they’re thinking about.

Yet babies begin to develop language skills long before they begin speaking, according to recent research. And, compared to adults, they develop these skills quickly. People have a tough time learning new languages as they grow older, but infants have the ability to learn any language, even fake ones, easily.

For a long time, scientists have struggled to explain how such young children can learn the complicated grammatical rules and sounds required to communicate in words. Now, researchers are getting a better idea of what’s happening in the brains of society’s tiniest language learners.

|

|

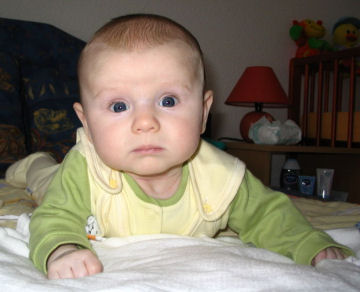

Long before they can talk, babies as young as 6 months start developing language skills. |

| Aleksandra Pospiech/Wikipedia |

The insights might eventually help kids with learning disabilities as well as adults who want to learn new languages. The work might even help scientists who are trying to design computers that can communicate like people do.

“The brain of the baby is a new frontier,” says Patricia Kuhl, codirector of the University of Washington’s Institute for Learning and Brain Sciences in Seattle. “Today, we talk about what we can discover by looking at the very youngest citizens of our culture.”

The learning process

Most babies go “goo goo” and “ma ma,” by 6 months of age, and most kids speak in full sentences by age 3.

For decades, scientists have debated how the brains of young children figure out how to communicate using language. With help from new technologies and research strategies, scientists are now finding that babies begin life with the ability to learn any language. By interacting with other people and using their superb listening and watching skills, they quickly master the specific languages they hear most often.

“The [baby] brain is really flexible,” says Rebecca Gomez, an experimental psychologist at the University of Arizona, Tucson. Babies “can’t say much, but they’re learning a lot.”

|

|

No one knows exactly how many languages are spoken around the world, but most estimates put the number at more than 6,700. |

| Seahen/Wikipedia |

Kuhl’s research, for example, suggests that the progression from babbles like “ga ga” to actual words like “good morning” begins with the ability to tell the difference between simple sounds, such as “ga,” “ba,” and “da.”

Because babies can’t tell a scientist what they’re hearing, researchers use a different strategy to check if they can tell sounds apart. In some experiments, for example, Kuhl plays recordings of a sound, such as “eeee,” over and over to one side of a baby. Then, the researchers broadcast another sound, such as “aaah,” from the baby’s other side.

If the baby turns to the new sound, he sees a dancing toy—a reward that encourages him to respond to such changes. If he doesn’t turn, that suggests that he doesn’t hear the difference between the sounds.

Such studies show that, up to about 6 months of age, babies can recognize all the sounds that make up all the languages in the world.

“Their ability to do that shows that [babies] are prepared to learn any language,” Kuhl says. “That’s why we call them ‘citizens of the world.'”

|

|

At birth, babies have the ability to hear every sound spoken in every language around the world—when they’re not crying, that is. |

| Inferis/Wikipedia |

About 6,000 sounds make up the languages spoken around the globe, but not every language uses every sound. For example, while the Swedish language distinguishes among 16 vowel sounds, English uses 8 vowel sounds, and Japanese uses just 5. Adults can hear only the sounds used in the languages they speak fluently.

To a native Japanese speaker, for instance, the letters R and L sound identical. So, unlike someone whose native language is English, a Japanese speaker cannot tell “row” from “low,” or “rake” from “lake.”

Starting at around 6 months old, Kuhl says, a baby’s brain focuses on the most common sounds it hears. Then, children begin responding only to the sounds of the language they hear the most.

In a similar way, Gomez has found, slightly older babies start recognizing the patterns that make up the rules of their native language. In English, for example, kids who are about 18 months old start to figure out that words ending in “-ing” or “-ed” are usually verbs, and that verbs are action words.

Language on the brain

Scientists are particularly interested in the brains of people who speak more than one language fluently because that skill is hard to acquire after about age 7.

In one of Kuhl’s studies, for example, native Mandarin Chinese speakers spoke Chinese to 9-month-old American babies for 12 sessions over 4 weeks. Each session lasted about 25 minutes. At the end of the study, the American babies responded to Mandarin sounds just as well as did Chinese babies who had been hearing the language their entire lives. (English-speaking teenagers and adults would not perform nearly as well).

To get a better idea of how an infant easily does what an adult often struggles to do, Kuhl puts a soft hat, called an electrode cap, on a baby’s head. The cap enables scientists to measure electrical activity in the brain. The amount and location of electrical activity show how much work different parts of the brain are doing.

|

|

This baby is wearing an electrode cap—which painlessly monitors electrical activity in the brain during experiments. |

| Patricia Kuhl, UW Institute for Learning and Brain Sciences |

The measurements show that the way the brain responds to speech changes dramatically between 6 and 12 months of age. The measurements also show connections forming between parts of the brain that recognize speech and the part that controls the production of speech. If a child regularly hears two languages, her brain forms a different pathway for each language.

However, once the brain solidifies those electrical language pathways by around age 7, it gets harder to form new ones. By then, a baby’s brain has disposed of, or pruned, all the unnecessary connections that the infant was born with.

So, if you don’t start studying Spanish or Russian until middle school, you must struggle against years of brain development, and progress can be frustrating. A 12-year-old’s brain has to work much harder to forge language connections than an infant’s brain does. Yet in the United States, learning foreign languages usually begins as late as high school.

“Fighting biology makes [kids] hate French,” Kuhl says. “We ought to be [learning new languages] between ages 0 and 7, when the brain does it naturally.”

Learning from the baby brain

Electrode-cap experiments also show that the stronger the response of a 7-month-old baby’s brain to the speech sounds of his native language, the more words he’ll speak by age 3. Measurements like these could help scientists identify early on which children are going to have trouble learning to talk. If these kids got extra attention in their preschool years, they might be less likely to fall behind once they enter first grade.

|

|

Different languages use different alphabets and different combinations of sounds to create words. Pictured here is a street sign in both Kannada (an Indian dialect) and English. |

| Muriel Gottrop/Wikipedia |

Understanding the circuitry of the baby’s brain might also help scientists design computers that learn languages as easily as babies do. Useful as computers are, they cannot understand a wide range of voices and communicate like people do.

For teenagers and adults who want to learn new languages, baby studies may offer some useful tips too. For one thing, researchers have found that it is far better for a language learner to talk with people who speak the language than to rely on educational CDs and DVDs with recorded conversations.

When infants watched someone speaking a foreign language on TV, Kuhl found, they had a completely different experience than they did if they watched the same speaker in real life. With real speakers, the babies’ brains lit up with electrical activity when they heard the sounds they had learned.

“The babies were looking at the TV, and they seemed mesmerized,” Kuhl says. Learning, however, did not happen. “There was nothing going on in their brains,” she says. “Absolutely nothing.”

Going Deeper: