Better chow yields more milk

A more nutritious form of corn for dairy cows boosts farm profits, teen investigator finds

By Sid Perkins

Sometimes less really is more. Though a variety of corn known as brown midrib doesn’t grow as tall as other types of corn, it does provide cows with better nutrition. The rub: It costs more. But the value of the bonus milk produced by cows fed the short corn more than covers its extra costs, a 15-year-old dairy farmer now reports.

Many farmers feed their dairy cows silage. This includes not only grain but also the shredded leaves and stems of the plants from which the grain had been harvested. The taller the plants are, the more silage farmers can harvest. But height isn’t everything, finds Bennett Lee Gibson, a freshman at Fremont High School in Ogden, Utah.

Previous studies had shown that cows can more easily digest silage from brown midrib corn. (This variety takes its name from the brown veins in the plant’s leaves.) Brown midrib silage also boosts milk production. But farmers had worried that the money gained from this bonus milk might not exceed the cost of the high-quality corn.

So Gibson decided to put the question to a test. A scientific one that used his farm and its animals. “Ahead of time, it was scary,” he notes. “There was no telling how the experiment would turn out.” At risk were the teen’s profits.

Many varieties of corn grow from 8 to 12 feet (2.4 to 3.7 meters). But brown midrib corn typically reaches heights of only about 10 feet, says Gibson. So planting brown midrib corn would yield the teen about 7 tons less silage per acre (0..4 hectare) than if he had planted a taller-growing variety. Together with the higher costs of the seed, it meant he would spend an extra $1.54 per week to feed a cow brown midrib silage.

But cows have an easier time digesting brown midrib sileage. This plant puts less lignin into its cell walls. Although lignin adds strength to the cell walls, livestock can’t digest this material. So brown midrib’s lower lignin content means cows’ bodies can use more of what they eat. (The plant’s lignin shortage also explains why the plants are relative midgets: Their stems are too weak to grow as tall as other corn plants.)

Gibson found that feeding cows brown midrib silage definitely put more money in his wallet. On average, cows eating this feed produced about 5.65 pounds (about 2.6 kilograms) more milk per day than cows fed typical corn silage. That, in turn, put an extra $5.60 per cow into his wallet each week.

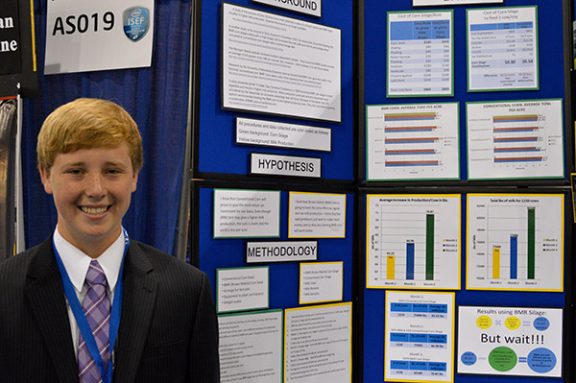

Gibson presented his findings May 13 in Phoenix, Ariz., at the Intel International Science and Engineering Fair. The Society for Science & the Public, which created the fair in 1950, still runs the competition. (SSP also publishes Science News for Kids.)

So feeding dairy cows brown midrib silage definitely pays off, Gibson concludes. And the benefits add up quickly. For a dairy milking 1,000 cows, feeding them brown midrib silage can boost profits by more than $292,000 per year. (That’s a lot of moo-lah!)

Power Words

Brown midrib corn A variety of corn that has less lignin in its cell walls. The plants are shorter and yield less food for cows and other animals that feed on the shredded parts of these plants. However, the plants are more easily digested and therefore more nutritious.

lignin A natural substance that helps strengthen the cell walls of plants. Although lignin is made from a large number of sugar molecules, which should provide energy, livestock can’t digest this material because of the way its sugars are chemically bonded together.

silage Chopped plant material fed to cows or other cud-chewing animals such as sheep. Silage typically includes all portions of the plant that grew aboveground (but no roots).