Big Viking families got away with murder

Killers were more likely to have large, extended clans, and their victims small ones

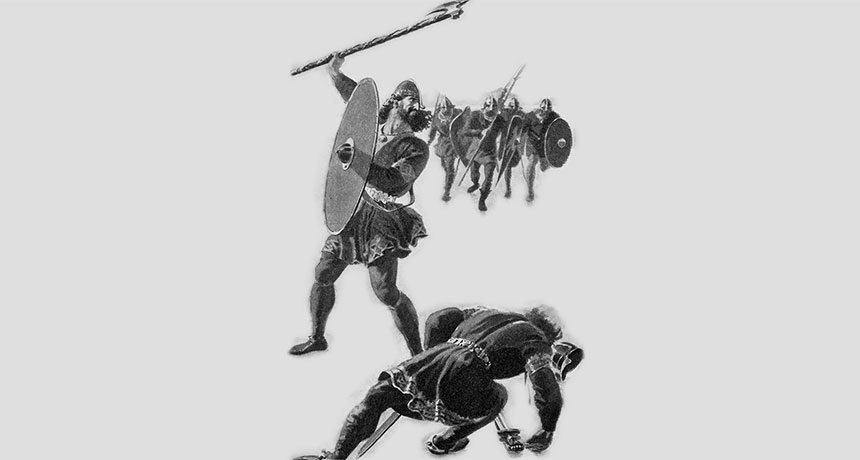

Killings in Viking-era Iceland, such as the one depicted here, were largely carried out by men whose families greatly outnumbered those of their victims, researchers say. Differences in family size may have long influenced who killed whom in small societies.

Andreas Bloch/Wikimedia Commons

By Bruce Bower

Murder was a family affair among Iceland’s Viking settlers. And the bigger the family, the more murderous it could be.

Vikings have a long tradition of writing down their family histories in epic stories. Called sagas, these tales told of war and long voyages. They included births, marriages, migrations and deaths. Researchers gathered data from three of these family histories. And when it came to murder, family size was key, they now report.

Viking killers in Iceland had nearly three times as many relatives as their victims did, says Robin Dunbar. An evolutionary psychologist, he works at the University of Oxford in England. Vikings who murdered five or more people came from the biggest families, his team found.

Iceland is an island nation in the North Atlantic Ocean. Its first settlers were Viking explorers who arrived from Europe in the late 800s. Dunbar’s team studied sagas written by three Icelandic families between 900 and 1100. Their tales described feuds and murders. They named 1,020 people, spanning six generations. For each named individual, the researchers mapped out a network of relatives. This included people they were related to by birth or through marriage.

The three sagas cited 153 killings. And the death toll was high: roughly one in every six men. Just six Vikings were involved in almost half of those deaths. Each of these killers took the lives of between 5 and 19 people. The most successful slayers came from large families. Their victims, in contrast, came from small families. A desire for more land may have been the motive for many of the killings.

Under Norse law, a murder entitled the victim’s relatives to either a revenge murder or money to compensate them for their loss. It appears that the murderers’ big families discouraged the smaller families from seeking revenge.

Most murders had been committed by men who killed just once. Here, the killers usually had only slightly bigger families than their victims. These murders were probably unplanned, Dunbar’s team says. They may have been triggered by an insult or some argument.

The researchers described their findings online September 20 in Evolution and Human Behavior.

Murder rates tend to go up when there are few or no authorities to enforce social order, Dunbar says. “The real issue is not that there were so many murders among Icelandic Vikings, but that murders were carefully calculated based on knowing whether one had a sufficient family advantage to take the risk.”

There is even a mathematical formula that addresses this. During World War I, a British engineer calculated the advantage that a larger group has over a smaller one in a fight. The bigger group’s advantage gets much larger as the size difference between the groups increased, he showed.

Dunbar’s team found that the same thing among the Icelandic Vikings. The bigger the difference in family size, the more likely someone was to get away with murder.

It’s rare to find research on how family size might encourage murder. It’s even rarer to find that kind of study on preindustrial groups like the Vikings, says Dominic Johnson. He’s a political scientist at Oxford who was not involved in the new research. Johnson has studied how group size affects whether an animal or human might attack.

Today, big families can mean extra protection on the playground or the school bus. Which means that perhaps the Vikings weren’t so different from us after all.