In 2024, bird flu posed big risks — and to far more than birds

Cows, elephant seals and polar bears have been among its unexpected casualties

An elephant seal and two young pups were photographed on a Península Valdés beach in 2022. A year later, few of the pups born in this part of Argentina survived. A massive H5N1 infection killed off a possible 17,000-plus southern elephant seal babies.

LUIS ROBAYO/AFP/Getty Images Plus

News reports of bird flu striking huge flocks of birds — including farmed poultry — have been ongoing for more than two years. Still, “most people have no idea that we are in the middle of a wildlife emergency — an animal pandemic,” says Michelle Wille. A viral ecologist, she works at the Peter Doherty Institute for Infection and Immunity in Melbourne, Australia.

She’s been studying bird flu. And the current panzootic — the animal equivalent to a human pandemic — is “very concerning,” she says.

This new variant of bird flu is what’s called highly pathogenic avian influenza, or HPAI. That means this virus is especially deadly to birds. Water birds, such as ducks, naturally carry avian flu with little or no or sign of sickness. But when flu viruses shuffle between farmed poultry and waterfowl, viral variants can emerge and spread. These may now make the virus super lethal to birds.

That appears to be what’s behind the new flu variants spreading around the globe. And birds are not the only victims.

Indeed, since the current outbreak emerged in Europe three years ago, bird flu has shown up in at least 50 mammal species around the globe. That’s far more than the dozen or so kinds of mammals that bird flu is known to have sickened during previous outbreaks.

Infections are hitting some animals so badly and in such large numbers, Wille says, “that this may be the nail in the coffin for some species.” By that, she means they could die out.

Influenza viruses come in many types. These are designated by numbers. This one is H5N1.

Each numbered virus can evolve into a range of variants, too. Variants can differ greatly in how they spread, which animals they’ll sicken, how sick they’ll make their victims and more.

When a variant behaves in a very new way, scientists refer to it as a new strain. And although H5N1 has grabbed headlines throughout 2024, the current variant actually emerged in Europe four years ago. It didn’t really become a big global threat until late 2021.

Since then, though, it’s thought to have killed millions of wild birds.

In Peru alone, more than 100,000 wild birds have died. Russia and Canada have documented tens of thousands more bird deaths. In the United States, roughly 10,000 wild birds have tested positive for avian flu. And in October 2023, H5N1 arrived in the Antarctic region for the first time. It killed a type of seabird — skuas — in the Falkland Islands there, as well as albatrosses and gentoo penguins.

Beyond birds, a polar bear on the North Slope of Alaska, way above the Arctic Circle, died from this flu late in 2023. Last December, the state’s veterinarian confirmed it had H5N1.

That same month, news came of a devastating die-off of southern elephant seal pups in Argentina. Researchers had collected data on three beaches where the seals haul out to calve. Most of the babies died from bird flu. Indeed, by the end of November 2023, only five in every 100 pups were still alive.

If this same rate of losses from H5N1 happened throughout the regional population last year, the researchers noted, “it is estimated that more than 17,400 [pups] may have died in this epidemic.”

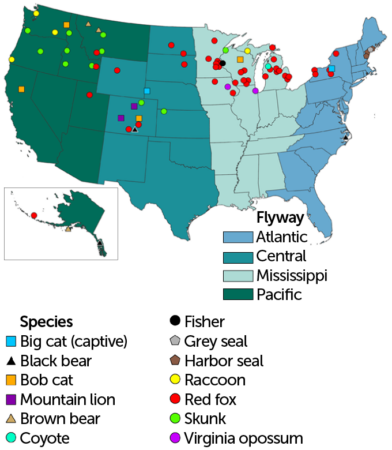

Since then, H5N1 infections have been hitting poultry farms, dairy cattle — and the occasional farmer. And then there’s felines. Cats big and small have sometimes died. For instance, the virus has killed at least 22 mountain lions. It also sickened at least 10 bobcats, killing at least seven of them. Other big cats to die of this virus: a captive leopard in New York and a captive tiger in Nebraska.

Here, we answer some questions about how worried we should be as this virus continues to wend its way through animals around the globe.

If cows are infected, can we get bird flu from drinking the milk or eating cheese?

Traces of bird flu virus have been showing up in milk on U.S. grocery shelves. That’s led many people to wonder: Can drinking that milk make me sick? And the short answer is no. Here’s why.

This past spring, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) sampled grocery store milk in regions where infected cows had turned up. And FDA did find H5N1 viral fragments in about 1 in every 5 samples of the milk it tested.

Those fragments were viral RNA. That doesn’t mean the whole virus was present, notes Michael Osterholm. He directs the Center for Infectious Disease Research and Policy at the University of Minnesota. It’s in Minneapolis.

Raw milk — meaning it is unpasteurized — could host the virus. But grocery store milk has been heat-treated to a temperature that will kill bacteria and viruses. So it’s not surprising to find genetic remains of the flu virus in this milk, Osterholm says. This also means, he says, “we don’t have to be concerned about ‘Are we ingesting infective material?’”

What’s more, H5N1 is an “enveloped” virus. This type wraps itself in a blanket borrowed from the membrane of a cell from its host animal.

These viruses are “just a little bit wimpier than non-enveloped viruses,” says Meghan Davis. And that makes them “a little bit easier to inactivate.” It also means “there’s some reassurance that pasteurization ought to be working,” she says. Davis is an environmental epidemiologist, or disease detective. She works at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health in Baltimore, Md.

All this explains why experts warn that people should not drink unpasteurized (raw) milk. It might still have infectious bird flu virus in it.

If chickens are getting infected, is it safe to eat their meat — or that of turkeys and ducks? And what about eggs?

People will not get bird flu by eating properly prepared poultry, according to the FDA. The first step: Always cook both the eggs and the meat of these birds to temperatures that will kill off germs.

Next, make sure to wash hands with warm water and soap for at least 20 seconds before and after touching eggs or raw poultry. Similarly, counters, knives and cutting boards — or any kitchen equipment that touches eggs and raw meat — should be washed thoroughly with soap and water.

Keep in mind, most birds harbor some germs. So these safe-handling rules will help keep other commonly found germs, too, from sickening cooks and diners. Those germs include Salmonella, E. coli and Campylobacter.

Also, because flu-sickened birds show symptoms swiftly, “the chance of infected poultry or eggs entering the food [supply] is extremely low,” according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA). Farmers will see their animals are sick and cull them.

But it’s not just up to farmers. USDA also tests flocks for signs of infection. It sends inspectors to farms and to shops where birds are slaughtered to make sure all recommended steps to limit the risk of infection are being taken.

Is there a vaccine for this virus like there is for the COVID virus?

Over the past few years, three companies have developed vaccines for use against the H5N1 virus. All three received FDA approval to limit or prevent disease. So far this type of flu hasn’t posed a huge risk to people. But if things change, these human vaccines can be rolled out for widespread release.

One concern: Scientists note it could be hard to make a lot of vaccine quickly. The virus used in making a vaccine is usually grown in chicken eggs. But when bird flu is especially widespread, farmers may kill off many chickens that are sick or have been exposed to this virus. That can limit the availability of eggs for vaccine production.

Some companies are working to develop vaccines that could be made more quickly. These shots use the same technology that the COVID-19 vaccine does. But they are far from being ready to use in people.

If I get bird flu, how sick will it make me?

In general, H5N1 is very deadly to birds, such as chickens. But so far, it’s sickened few people. Right now, people working with animals that might be infected are at highest risk.

Four farmers with infected dairy cows got sick. So did nine workers who had contact with infected chickens or turkeys. One person in Missouri got H5N1 despite having no contact with cows or poultry. Someone that person lives with also got sick. So did two health care workers who had contact with that first Missouri person. These others hadn’t been formally tested for bird flu. As of late September, they were due to get tests for antibodies that should show whether they, too, had bird flu.

Do you have a science question? We can help!

Submit your question here, and we might answer it an upcoming issue of Science News Explores

Starting in March 2024, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, or CDC, set up a national program to watch for signs of human risk from the H5N1 virus. As of mid-September, it had monitored more than 4,800 people. It tested more than 240 who had been exposed to infected animals. Of those, it found only 14 cases in people.

Worldwide, only 29 human cases have turned up across nine countries. Seven people have died. By comparison, seasonal flu kills an estimated 300,000 people or more each year.

Some bird flu infections are mild. You might have no symptoms. But if you do get sick, you might have a cough, sore throat, pinkeye (conjunctivitis), a runny or stuffy nose, headaches or body aches. You might find yourself short of breath. Some people develop a fever and get very tired. More severe cases may cause diarrhea, vomiting, pneumonia — even seizures.

But the important thing to keep in mind is that so far, there’s been no sign of person-to-person spread of H5N1.