The color of body fat might affect how trim people are

Brown, beige, white? Upping the type that burns calories instead of storing them could become a key to health

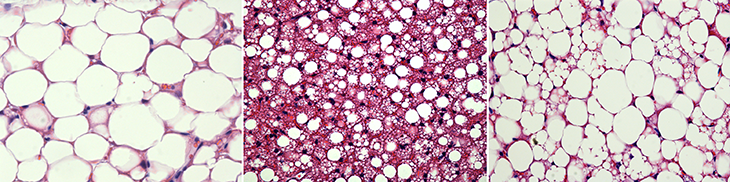

White fat stores energy, and brown fat burns calories. Scientists studying this type of body fat hope to find ways to boost its levels to help fight obesity and diabetes.

skynesher/E+/Getty Images

Fat sometimes gets a bad rap. It’s often linked with being overweight and poor health. But fat is an essential part of all living things. In our own bodies, fat lies beneath the skin and hugs our organs. Its job is to store extra calories until needed. Seems like a straightforward role. Or is it?

In fact, body fat is complex. Until recently, scientists thought people had only one type. Called white fat, it stores excess calories in molecules called lipids. Lipids can be broken down for energy when food is hard to find. White fat is what people think of when they think of body fat.

But some 50 years ago, researchers discovered that people also have brown fat. It actually burns calories.

Scientists first discovered brown fat about 500 years ago. They found it in hibernating marmots (also known as groundhogs or woodchucks). Only a small amount of body fat is brown. So for a long time, scientists thought brown fat was a gland that existed only in hibernating animals. Only in the last 100 years have they realized this “gland” is actually a special type of fat.

Scientists are still learning about brown fat. Studies have uncovered its importance for hibernating animals. That research helped show that brown fat plays a key role in how bodies use energy. And that link suggests that boosting brown fat in people might help them lose weight and perhaps treat certain chronic diseases, such as diabetes.

Wake-up call

Most body fat in animals, including people, is white. And it’s a life-saving tissue. Most animals don’t have a constant supply of food. Until fairly recently, most people didn’t either. White fat allows individuals to eat more than they need when food is easy to find. It stores those extra calories until food becomes scarce. Then the body burns it for energy to stay alive until more food shows up.

Hibernating animals take this to the extreme, explains Mallory Ballinger. She is an evolutionary biologist at the University of California, Berkeley. Hibernation allows many animals to get through harsh winter conditions. Bats, squirrels and bears, for example, all gorge themselves on food in fall. These mammals pack on the pounds — up to half their body weight — in preparation for a long, cold winter.

Animals don’t eat when they’re hibernating. Instead, they burn their white fat to keep their bodies running. But they only have so much fat to burn. To make it last an entire winter, these critters must use it slowly. Much more slowly than they normally would. To do this, they enter a state called torpor.

When in torpor, animals appear to be sleeping. But torpor goes much deeper than that, Ballinger says. In torpor, a body’s activities slow down. The heart may beat only a few times each minute. Breathing may become irregular. An animal may take several breaths and then stop breathing for several minutes — even up to an hour or more. Bodies in torpor also chill down. Instead of wasting energy keeping warm, a hibernating animal’s body can remain just above freezing.

But hibernating animals don’t stay in torpor all winter, Ballinger points out. Every week or two, they waken. And they stay awake for a day or so before going back into torpor. Biologists don’t know what triggers the wake-up or why it happens, she says. The duration and timing varies by species. However, she points out, all true hibernators go through this cycle.

In order to wake up, the animals have to warm up. That means going from a temperature just above freezing to their normal body temp in only a couple of hours.

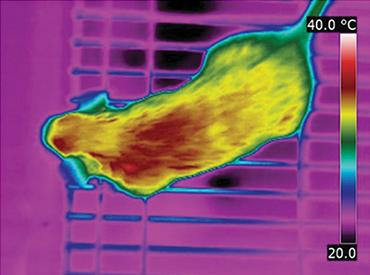

That’s where brown fat becomes important. Brown fat creates heat. If the outside temperature gets too cold, brown fat keeps the animal from freezing. It also pulls the animal out of torpor. As the brown fat gives off heat, it warms the blood, which then carries that warmth to the rest of the body.

This process burns up white fat, including white droplets packed in with the brown fat cells, Ballinger explains. That shows brown fat plays a critical part in how and when the body stores and uses energy. And it turns out that’s true not only in hibernating animals. It’s true in people, too.

Turning beige

Brown fat is brown because it’s packed with mitochondria (My-toh-KON-dree-uh). These structures are powerhouses within cells. They burn the fats, sugars and proteins that we eat. In most cells, this process creates a molecule called ATP that powers other reactions. But in brown fat, the mitochondria don’t make ATP. Instead, they produce heat.

Brown fat cells are “one of the most mitochondria-rich cells in our body,” notes Shingo Kajimura. He’s a molecular biologist at the University of California, San Francisco. He studies the role of brown fat in obesity and diabetes. Mitochondria are chock-full of iron. That iron, he explains, gives the cells their rusty brown color.

White fat cells are white because of the lipids inside. These cells don’t have many mitochondria. Their job is to store energy, not burn it. Although white fat usually stays white, researchers have discovered that under certain conditions some white cells will turn brown. Because these altered cells aren’t as dark as true brown fat, scientists call them beige fat.

White fat turns beige when the cells boost their mitochondria. The best trigger for this is cold temperatures. When people are exposed to cold, their bodies up their beige fat levels. It doesn’t take extreme cold to make this happen. Just two hours a day at 19 degrees Celsius (66 degrees Fahrenheit) for six weeks will trigger white fat’s browning. That’s cool enough to feel chilly, but not so cold that you start shivering, Kajimura says.

It takes just 10 days at warm temps for those beige cells to whiten again. “It’s an adaptive system,” Kajimura says. White cells turn beige when the body needs to burn calories for warmth. When that’s no longer necessary, burning extra calories could lead to starvation, especially when food is hard to get. So the beige cells destroy their mitochondria and become white again.

Making white fat burn calories

The fact that fat cells can change color might one day lead to treatment for people with obesity and related diseases. Obese people tend to have very little brown fat — much less than lean people do. That may be part of the reason why they struggle with their weight. Converting white fat to beige fat could give people a new way to maintain the balance of calories eaten and burned, Kajimura says.

He is one of many researchers trying to do just that. Although cold causes the body to make beige fat, cold temperatures can be hard on people. That’s especially true for older people and those with heart problems, Kajimura points out. Blood vessels narrow when people are cold. That helps prevent heat loss. But the heart has to work much harder to pump blood through those narrow passages. So cold temperatures could be dangerous for someone who already has high blood pressure.

Instead, Kajimura’s team is searching for cell processes unique to brown fat. These, he says, might be the key to making white cells burn calories. He and other researchers have found that calcium is very important in brown cells. How that calcium moves into and within cells seems to be key.

The UC-San Francisco researchers inserted a gene in mice that causes this calcium movement. In these rodents, the white fat cells began to make heat. What’s more, those cells began to soak up glucose and burn it. (Glucose, also known as blood sugar, is the sugar our bodies use for fuel.) People with type 2 diabetes have cells that don’t do a good job of using glucose. Adding this gene to their fat cells might help fight their disease, says Kajimura. And since the cells are burning that sugar instead of storing it, the gene might also help obese people slim down.

Kajimura added a gene to boost calorie-burning fat in mice. Claudio Villanueva instead removed one. He is a biochemist at the University of Utah School of Medicine in Salt Lake City. His team removed the gene that makes lots of proteins involved in storing energy from one group of mice. The gene is normally active in white fat but not in brown fat. A second group of mice kept the active gene but was otherwise genetically the same.

For four days, the mice were then kept at cool temperatures (4 degrees Celsius; 39 degrees Fahrenheit). Afterward, the researchers tested how well the rodents handled glucose. Mice without the gene had more beige fat cells. And they were able to manage levels of their blood sugar better than were mice that still had the gene.

“Having more beige [fat cells] can lead to better glucose control,” Villanueva concludes. “That could be beneficial for patients with diabetes.” He hopes this finding might one day lead to therapies that treat this serious disease by turning white fat cells beige.

Healthy fat through sleep

Another promising — and already available — option for turning white fat beige is melatonin. This hormone is produced by the brain when light begins to dim in the evening. As the body’s melatonin levels go up, we start to feel sleepy. It also helps to control body weight. Rodents given a daily melatonin supplement gain less weight than those that don’t get one, even when they eat the same amount of food.

This finding prompted cell biologists Dun-Xian Tan (now retired) and Russel Reiter to investigate how melatonin reduces weight gain. Both conducted their research at the University of Texas Health Science Center in San Antonio. They teamed up with two researchers in Spain. One of them, Ahmad Agil, is a neuroscientist at the University of Granada. Gumersindo Fernández Vázquez is an endocrinologist at the University Clinical Hospital La Paz in Madrid. (An endocrinologist studies the role of hormones in health and disease.)

This team used two types of rats to study how melatonin affects body fat. One strain of rat was obese and would develop diabetes. The other was lean and never got diabetes. In every other way, genetically, these rats were the same. Half of each strain were given their regular food for six weeks. The other half received the same food plus melatonin. Afterward, the researchers examined the fat just under the skin near the animals’ shoulder blades.

Obese rats given melatonin grew more beige fat over the six weeks. Melatonin didn’t change the amount of beige fat in lean rats. But it did make their brown and beige fat more efficient at turning food into heat. When put in a cold room, the lean rats had no problem keeping warm.

The obese rats also lost weight. Tan now suspects that melatonin might help people manage their weight, too. That would start by allowing natural melatonin levels to rise in the evening. “Keep a normal sleep time,” he advises. “And avoid any light exposure” at night. Sleeping in rooms with no lights, even small ones from device chargers or screens, is important. Through its effects on melatonin, Tan says, “Night [light] contamination is a critical risk factor for obesity or other diseases.”

Scientists are still working to understand the genetics behind brown and beige fat well enough to turn them into treatments for people who are obese or have diabetes. But until then, supporting healthy melatonin levels and getting good, regular sleep may be the best ways for people to boost these helpful fat cells.