A ‘book’ on every living thing

The biggest encyclopedia ever, with an entry for every living species, is available now at a computer near you.

By Susan Milius

Fish that weigh more than a refrigerator. Fish with glowing slime. Fish that look like cows—or at least did to the folks who named them cowfish (and these creatures do have long faces).

Some very odd creatures swim through the world’s waters. Now, getting to know them is about to get easier. Beginning last week, a new Web site went live. Called the Encyclopedia of Life (www.eol.org), this online book of life will offer basic facts on about 30,000 species—or kinds—of fish. That’s every type known.

This tally includes the first six species named in 2008: all damselfish from what are sometimes called Twilight Zone coral reefs in the Pacific Ocean. The fish are not well-known because they dwell deeper beneath the surface of the sea than standard SCUBA gear lets divers go. Scientists published the first formal descriptions of the six new species on New Year’s Day.

|

|

BLUE FISH. An artist who works with scientists made this image of the deep-blue chromis, a damselfish from the Pacific. It’s one of the first fish named in 2008; its official description was published Jan. 1.

|

| T. Clark |

But as impressive as 30,000 fish sounds, it’s barely a baby step for the Web site. Its developers dream of making it the largest biological encyclopedia ever, with a Web page for every living species.

True, there are already a lot of Web sites about living things, and a lot of encyclopedias too. But they’re not the best tools for working biologists, say the encyclopedia’s designers. Scientists need sites with information that has been double-checked by other scientists. An ideal site would include links to all the basic research, from genetics to detailed pictures of museum specimens. The dream site would automatically update itself as new research is published. Finally, even people who aren’t scientists should be able to use such a site to identify what’s living in their backyards—or anywhere else in the world.

Think of it as one humongous book that can keep growing in size—to millions of pages. If those pages were made of paper, the book would become unwieldy and heavy and hard to update. However, because it’s available online—and only online—anyone and everyone with access to a computer can browse its virtual pages effortlessly. Moreover, those new pages can be added quickly—indeed, the same day new information becomes available.

One wish

The dream for a better encyclopedia comes from biologist Edward O. Wilson of Harvard University. In 2007, he was invited to that year’s TED conference, a meeting of leaders in technology, education, and design. Each year at this meeting, several participants get a chance to make a wish in front of the crowd and explain why that wish deserves everybody’s help. In 2007, Wilson wished for an encyclopedia of life.

For starters, it could speed the process of naming species, he argued. This naming process is something that few people understand. For more than 250 years, scientists have been naming species, using the same basic rules (two names, in Latin). So there’s a widespread belief that by now just about everything already has a name, Wilson says.

But that’s not true. Although biologists have assigned formal names to about 1.8 million species, new ones are being discovered all the time. Wilson estimates that among plants alone, 2,000 new species are named every year. That’s more than five a day. Nobody knows how many more species await discovery, but some biologists suspect another 8.2 million species remain unnamed.

|

|

FIRST FLOWERS. The first plants in the encyclopedia will be members of the potato family. It’s full of celebrity cousins, such as the tomato and tobacco. The family has plenty of members that don’t grow in gardens, such as this Solanum urticans. The information comes from a scientists’ database called Solanaceae Source.

|

| M. Nee/NY Botanical Garden |

And scientists probably haven’t even discovered all the really important species. For example, biologists have been studying life in the sea for hundreds of years. Yet within the lifetimes of today’s college seniors, biologists finally described a group of microscopic bacteria called Prochlorococcus. Great masses of them float in the oceans performing important work, harvesting energy from sunlight that will later help fuel the microbes’ predators.

Describing an organism is just the first step in understanding it. Yet that first step isn’t easy. To figure out whether a funny-looking fish or plant, or speck of marine life, really is a new species can take a great deal of research, says Wilson. A scientist has to look at creatures like it, or at really good pictures of them. Those specimens could be in museums anywhere in the world. The describer also has to read about related species. Some of these descriptions appear in fragile old books, available in only a few libraries. A good Web encyclopedia though would help a scientist find all these things in one convenient place, Wilson argued. And it would save scientists a lot of travel time—and expense.

Turning pages

The oldest books that a scientist might want online were published long before anyone had a clue what electricity was, much less how to build a 21st-century computer. So several libraries around the world are electronically scanning rare, fragile old books and then posting digital images of them, page by page, online. When the Encyclopedia of Life gets going, people will be able to click on the page for a species and from that, get a look at the book page of the oldest description. Some of the books being scanned are several hundred years old with yellowing pages and a weird spot or two. The project already has some books online (See www.biodiversitylibrary.org/).

Thomas Garnett of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History in Washington, D.C., heads the scanning team. During a recent visit, he led this visitor into the museum’s basement to see the project in action. (The museum is old and has huge collections of just about everything, but the basement hallways are wide and well lit. Alas, no piles of dinosaur bones spill out of closets.)

The trip ends up in a large room with a computer desk pushed back against the wall. A framework above it supports a tent of black fabric that falls down around the desk. In the center of the desk, a small book with yellowed pages rests in a V-shaped cradle. The shape prevents elderly books from spraining their backs. A pair of cameras hangs from the frame, lined up just so. The workers photograph each pair of open pages at the same time, with a “ja-chick” sound and a flash of light. The black tent protects the setup and keeps those flashes from disrupting nearby workers. A person running one of these stations can copy about 3,000 pages each day.

|

|

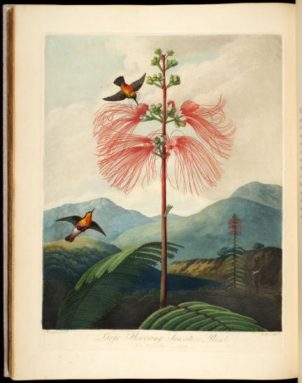

SCAN THIS. A page from a botany book published in 1807 shows a Calliandra grandiflora. The electronic-scanning team has copied this book page by page and posted it on the Web. Old biology books such as this one will eventually be linked to encyclopedia entries.

|

| Biodiversity Heritage Library |

For more modern content, the producers of the encyclopedia are turning to scientists who have already created databases with accurate, up-to-date, computerized information. The fish pages—among the first to debut in the encyclopedia—will come from a project called FishBase, headquartered in the Philippines. It won’t have all the fancy links planned for the final version of the pages. For instance, the site may not yet have details about the mucus products of the shining tubeshoulder fish, but it should give pictures of honeycomb cowfish. It will also provide the weight of an adult northern blue-fin tuna—these can tip the scales at about 1,500 pounds (680 kg), which is around the combined weight of four kitchen refrigerators.

Next will come pages of plants in the nightshade family, put together by botanists around the world. This varied group of plants includes tomatoes, tobacco, and potatoes as well as their wild relatives. It’s a fine way to celebrate the International Year of the Potato. (Not a joke. See “It’s Spud Time”.)

One for all

As much as scientists may look forward to using the new encyclopedia, it isn’t just for them, says Mark Westneat of the Field Museum of Natural History in Chicago. “The other audience we’re targeting is middle schoolers,” says Westneat. “They’re very quick. They’re interested. They’re also capable of handling complex ideas.” Plus, they’re agile Web surfers.

And soon, possibly within a year, these students may be able to help construct the encyclopedia. Everybody’s going to get a chance. The project’s executive director, James Edwards, also based at the Smithsonian, says he’s already working on ways for nonscientists to contribute. The plan is evolving, he says, but he imagines a system where anyone can submit a photograph or information. Once a scientist verifies a species’ identification and information, that image will receive some mark of approval. The best images will be added to the encyclopedia.

So practice taking clear pictures. With perhaps 10 million species on Earth, the encyclopedia is going to need a lot of photographers.

Going Deeper: