‘Boot camp’ teaches rare animals how to go wild

Scientists teach captive-reared endangered species such vital skills as finding food and avoiding predators

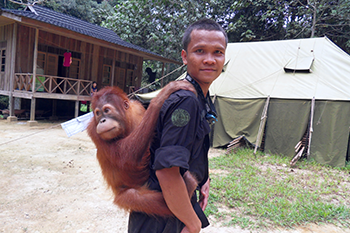

This young orangutan has lived its whole life in the jungle. Others raised in captivity no longer know what it means to be wild. Before they can join this one, they must go to boot camp for basic survival skills.

Lillian Tveit/iStockphoto

The first release of young black-footed ferrets into the wild was a disaster. It was 1991 and scientists had released 49 animals in Shirley Basin, north of Medicine Bow, Wyo. Nearly every one died in the first year, mostly in the jaws of coyotes and badgers.

The animals had been raised in captivity. Their species, Mustela nigripes, had at one point been thought extinct. But after a small population was rediscovered in 1981, scientists captured the remaining 18 animals. The goal was to breed the ferrets and then reintroduce their species back into the wild.

But it wasn’t as easy as just letting young ferrets loose, the scientists quickly learned. Having grown up in a sheltered environment, the animals didn’t know how to hunt. They also didn’t know how to avoid predators.

And they paid the price.

Now, before any are released into the wild, black-footed ferrets must go to “boot camp.” It’s an intensive period of training when they learn how to fend for themselves. The hardest part for most of them is recognizing — and escaping from — those animals that want to make a meal out of them. But the program has been a success. As of 2017, some 350 black-footed ferrets could be found roaming North America, largely in Wyoming, South Dakota, Montana, Arizona, Colorado and Kansas.

Black-footed ferrets are now a poster child for something called “rewilding.” This is the careful and planned reintroduction of animals to an environment from which they had disappeared.

Scientists have been working to rewild many animals around the globe. That’s because wild animal species are quickly disappearing in many parts of the world. Humans are destroying the places where they live. We are doing this by building cities, logging forests, mining rocks and taking oil and gas out of the ground. Sometimes people hunt too many animals for their populations to recover.

All of this puts more and more animals are at risk of extinction. To save them, some of these animals are being bred and raised in captivity. Examples include the eastern quoll (an Australian marsupial) and the scimitar-horned oryx (a type of African antelope).

For many species, though, there is a problem: If the animals are to survive long enough to have babies, they must be fed and protected from predators. But such protection stops the young ones from learning how to hunt for their own food and find shelter.

And here’s where scientists are stepping in to help.

Robo-badger and a stuffed owl

Thirty-seven years ago, a Wyoming rancher’s dog carried home a strange-looking animal carcass. The slim, cream-and-black creature was about the size of a house cat. Its feet, face and tail tip were black. The rancher didn’t recognize it. Intrigued, his wife asked some wildlife biologists if they could identify the animal. And to their shock, the could. It was a black-footed ferret — a creature they had assumed was extinct.

These members of the weasel family are the only ferret native to North America. Ferrets mostly eat prairie dogs and use their burrows for shelter. But early in the last century, as people turned prairie into farmland, many populations of prairie dogs disappeared. Those animals now occupy less than 2 percent of their original habitat.

Story continues below image.

The rancher’s property had enough prairie dogs to support a small population of black-footed ferrets. But six years after their discovery, the ferrets got sick with a serious disease. Just 18 survived. Government biologists raced to round up each one and place it in captivity. The goal was to one day release future generations of them back into the wild.

Since that first failed attempt at rewilding, all black-footed ferrets raised in captivity attend boot camp before release. This takes place at the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service’s facility in Fort Collins, Colo. Wildlife biologist Dean Biggins of the U.S. Geological Survey developed the program for toughening up these creatures. He started by bringing in Siberian polecats from China.

Siberian polecats are the black-footed ferrets’ closest relatives. Biggins figured they would respond to his training much as the ferrets would. There were so few ferrets that he didn’t want to risk testing boot-camp techniques on them, in case they failed.

Biggins and his fellow biologists raised the polecats in the same 1-by-1.2-meter (3-by-4-foot) cages in which the ferrets were reared. They then tested their reactions to pretend predators. This included something Biggins and his co-workers called “the robo-badger.”

It was a roadkill badger. The researchers mounted it onto the chassis of a toy truck, then had it chase the polecats around. “But robo-badger was slow,” Biggins recalls. “And although he looked like a badger, he just didn’t behave like one.”

So the researchers obtained a more convincing stuffed owl, also a ferret predator. Biggins tied the stuffed owl to a line so he could make it swoop down on the polecats.

When the first generation of polecats born in captivity saw the owl, they fled to their boxes. There they cowered for hours. But each new generation became less wary. By the fourth generation, the owl didn’t worry them at all.

Story continues below slideshow

Re-scaring these potential prey

The results were no surprise. Biggins hoped his next experiment would show was that this unwary behavior was reversible. He wanted the polecats to fear those predators again.

To do this, he raised the third generation of polecats in larger, outdoor pens. These resembled the polecats’ natural environment. Biggins hoped this would help the babies relearn how to be wary and avoid animals that viewed them as lunch.

While it was a relatively normal habitat, the animals were still protected from predators. The animals had to live long enough to unlearn bad habits, of course. To Biggins’ relief, each new generation became more and more frightened of the owl. Eventually, their reactions were close to normal.

“Why that happened, we don’t know,” Biggins says. “Was it simply lack of human attention? Or being in burrows where mom can transmit escape behavior? Or are they more physically fit?”

Biggins’ team is now using the same technique with ferrets. He knows not every animal is ready for release. Still, he points out that it’s too expensive to test each ferret. They are simply given the best possible training. The rest is up to them.

And he must be doing something right. Black-footed ferrets released today have survival rates 10 times better than those raised in the original small cages.

Puppet parents

California condors look like something out of prehistory, because, in a way, they are. “They lived back 10,000 years ago with American mastodons and saber-toothed cats,” says Michael Mace. He is the director of animal collections and strategy at the San Diego Zoo Safari Park in California. “Of all the giants of that time,” he notes, “the condor is the only one to be with us today.”

The condors are a type of vulture, birds that scavenge dead animals as food. Their wing span is just over three meters (nearly 10 feet), making them the largest bird in North America. They have bald heads and black feathers with patches of white on the underside of their wings.

Though the birds outlived mastodons and saber-toothed tigers, they are in trouble now. Habitat destruction in the American West and Southwest, along with hunting, has dramatically reduced their numbers. Indeed, by the late 20th century they were nearly wiped off the face of the Earth. And the major reason: their vulture habits. Some of the carcasses the birds scavenged had been riddled with lead from bullets. That heavy metal is toxic. Over time, it sickened the condors — and they died.

By 1987, there were just 22 California condors left. Biologists rounded them up and took them to zoos in San Diego and Los Angeles, Calif. Protected and fed, these birds reproduced. By 1991, there were enough condors to start releasing them back into their ancestral homes — California, Arizona, Utah and Baha, Mexico.

But first, the condor chicks had to learn how to be wild. Like many birds, California condors form tight bonds — called imprinting — with their caregivers. They see these caregivers — whether condor or human — as a parent. They try to imitate them.

The zookeepers had to make sure the chicks didn’t look to a human as their parent. That wouldn’t be healthy for wild birds. To avoid this, the researchers used a leather hand puppet to feed and care for the chicks. That puppet looked like an adult condor. The staff stood behind a curtain, thrusting the puppet toward the chicks through a hole in the fabric. A recording of a babbling brook masked the sound of human footsteps and other unnatural noises.

Zookeepers learned how to care for chicks by watching videos of condor parents. Proper care requires more than just placing raw meat in the nest. Just like real condor parents, the puppets must poke at the meat, nudging it toward the chicks.

The puppet birds also play with the chicks and groom them. When a chick tries to bite a “parent” or strays too close to the edge of the nest, the puppets even discipline the chick. The puppet will hit the misbehaving offspring, though, of course, not hard enough to injure them.

But the chicks also need to see real adult condors. So zookeepers installed a big window in the chicks’ enclosure. It looks onto the aviary where the chicks can see captive adult condors flying by.

“We are always reinforcing to the chicks, ‘You are a condor, not a person,’” says Mace.

Story continues below video.

Despite all of these precautions, the first condors released into the wild were kind of wild, but not in a good way. “It was like a school yard without a teacher monitoring them,” recalls Mace. “They would fly into people’s yards, tear up the cushions on their lawn chairs, drink out of their swimming pools and stand on their porches.”

But by the time those birds started having babies of their own, the condors had learned to stay out of trouble. And when it came time to release the next batch of condors from the zoo, they now had adult role models in the wild. Explains Mace, things went smoother after that.

Today, there are 275 California condors flying free in the American west and Mexico. Another 200 or so are in captivity, awaiting their turn to fly free.

Jungle school

While humans don’t make good condor parents without a disguise, no such camouflage is needed when working with young orangutans. Humans and orangutans are both primates. As such, we have much in common. And that has proven useful in the southeast Asian nation of Indonesia.

Some 55,000 orangutans live on the Indonesian island of Borneo, according to one estimate. On the neighboring island of Sumatra, there are another 14,000 or so. That may sound like a lot, but all the orangutans in the world could fit into one U.S. football stadium — with room to spare. Their numbers have been dwindling due to habitat destruction and hunting.

Today, roughly 1,200 orangutans live in rescue centers. Some of these tree-dwelling apes were brought to them from recently logged areas. Others came from private homes, where they had been kept illegally as pets. And still others came from circuses where they were made to perform — riding bicycles, or dancing.

“Many have lost their culture to some extent,” says Leif Cocks. “We try to replace it by showing them how to be orangutans.”

Cocks is a biologist and an expert in primate behavior. He runs a rescue center in the Indonesian jungle called the Orangutan Project. The center is in Sumatra near Bukit Tigapuluh National Park (which is also known as “30 Hills”). It is home to about 175 rescued orangutans.

Before their training can begin at 30 Hills, human caregivers check each animal for disease. They don’t want to run the risk of reintroducing an orangutan into the wild only to have it spread disease to others.

When it has a clean bill of health, the animal can meet its fellow orangs. Through trial and error, each slowly learns how to socialize with others. It also goes to “jungle school” from 9 a.m. to 3 p.m.

In jungle school, human caregivers carry the animal into a large enclosed space within the jungle. There, it can climb trees and swing on vines, building up its strength. The orangutan also learns an important skill: assessing which branches and vines are strong enough to take its weight.

If they don’t recognize specific fruits and plants that are good to eat, human caregivers will help the animals out. An orangutan at 30 Hills must be able to do two things before qualifying for release. First, it must identify 120 different food sources, including termite mounds. Second, it must be able to successfully build its own nest.

Cocks says the whole process of learning to be an orangutan takes an average of three years.

Even then, orangs go through what’s called a “soft release.” This means they have small radio trackers implanted in their shoulder blades. That lets caregivers monitor them and return to help animals that run into trouble. An orangutan’s soft release can also take up to three years.

Cocks estimates that more than 1,000 orangutans have been reintroduced into the jungles of Indonesia since the late 1960s. The problem now is that much of their habitat is gone. Unless we conserve and restore jungles, he says, there may be nowhere for them to go, no matter how much help people give them while growing up.

Such rewilding efforts are clearly costly and time-consuming. They also may be the only way to ensure that species on the brink of extinction — often due to human activities — get a second chance at survival.