Bringing fish back up to size

Changing the way we fish may help rescue a population's shrinking fish

|

|

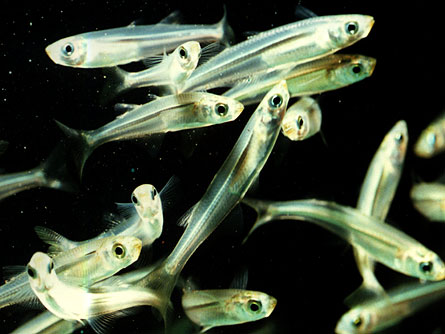

Silversides, fish used as bait, saw a reverse in a downward trend in size when researchers switched from catching the bigger fish to catching randomly over generations.

|

| D. Conover |

Anyone who has ever gone fishing probably knows this general rule: Keep the big ones, throw the smaller ones back. The idea behind the rule is simple — the larger fish are assumed to be older. If you were to keep the smaller ones, they would not be able to reproduce, and the fish population would be in jeopardy.

That rule may have done as much harm as good. Fishing out the largest fish from a population can have an unwanted consequence: Over time, fewer adult fish get really big. If only the smaller fish can reproduce, then future generations of the fish will tend to be smaller. This is an example of evolution in action. Evolution is the process by which species adapt and change over time. The survival of the smallest fish is an example of an evolutionary process called natural selection.

For years, scientists have wondered if the fish would stop shrinking if such catch-big fishing practices were stopped. Now, David Conover, a fish scientist at Stony Brook University in New York, has an answer — at least for the silverside, one particular kind of fish. “The good news is, it’s reversible,” he says. “The bad news is, it’s slow.” Conover should know — he spent five years studying if fish would shrink and then another five years studying if fish could regain their former size..

To set up the experiment, Conover and his team caught hundreds of silversides, small fish usually used as bait, in Great South Bay, New York. The tiny fish were divided up into six groups. For two groups, Conover followed the “keep the large ones” rule and took out the biggest fish. In fact, he fished out all but the smallest 10 percent. For two other groups, he removed only the small fish. For the last two groups, he removed fish at random.

After five years, he measured the fish in each population. In the two groups where he had regularly removed the largest fish, the average fish size was smaller than the average size in the other groups. Here was evolution in action: If only small fish survive to reproduce, then future generations of fish will also tend to be small.

For the second five years of his experiment, Conover changed the rules. Instead of removing fish based on size, he took fish randomly from each group. At the end of the experiment, he found that the fish that were in the “keep the large ones” group for the first five years had started to get larger again. These fish were on the road to recovery.

Those fish didn’t return to their original size, however. Conover calculates that it would take at least 12 years for the average size of a silverside to return to the original length. In other words, it takes less time to shrink than it does to recover. For other fish that don’t reproduce as often as silversides, it may take many times longer.

Conover’s study shows that organizations in charge of fisheries need to keep evolution in mind. Something like this could be going on with fish in the wild, though it’s much harder to test. For example, it may be time to get rid of the “keep the large ones” rule, since lab experiments show it causes the fish to shrink. Instead, fisheries managers might allow people to keep fish that are neither small nor large — which ought to help fish stay their original size.

Power Words:

(adapted from materials from the Yale-New Haven Teachers Institute: http://www.yale.edu/ynhti/curriculum/units/1979/6/79.06.01.x.html)

biological evolution: the slow process by which life changes from one form into another

(adapted from the Yahoo! Kids Dictionary: http://kids.yahoo.com/reference/dictionary/english/entry/natural%20selection)

natural selection: the evolutionary process by which organisms best adapted to their environment tend to survive and pass on their genetic characteristics to future generations, while those less adapted to their environment tend to be eliminated.