Bubbles could help remove trash from rivers

An airy curtain of them would divert trash to an onshore collection system

Bubbles can exert a powerful force to move items floating at a river’s surface. That’s the idea behind Dakota Perry’s creek-cleaning research project, which she described at the Regeneron ISEF competition this week.

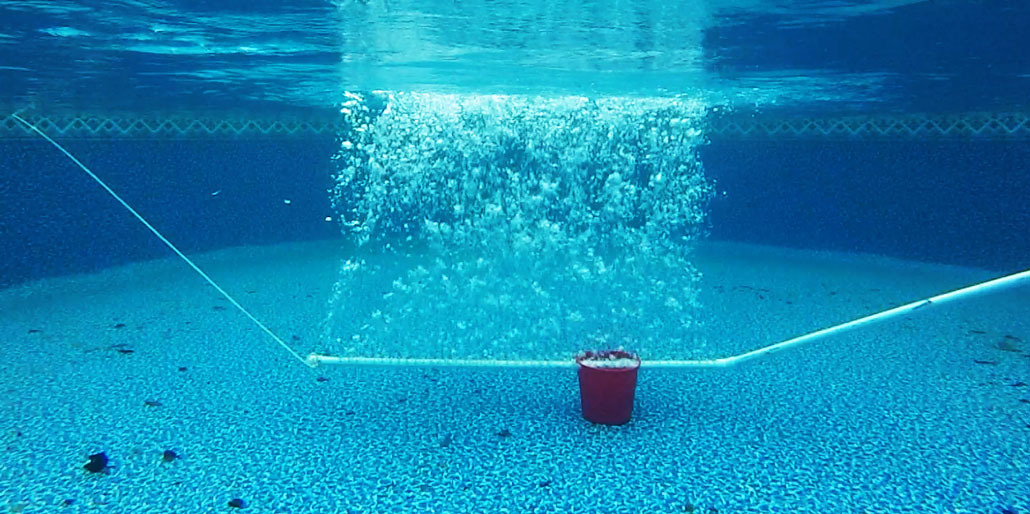

Tibor Kranjec /EyeEm/Getty Images Plus

By Anna Gibbs

ATLANTA, Ga. — The creek behind Dakota Perry’s house in Mobile, Ala., is often littered with trash. While spending time there with her dad, the high school sophomore would notice plastic bags, bottles and cups strewn across the water and collecting along the shoreline. But where some might opt for a community trash pick-up, Dakota wondered if there wasn’t a better way. The teen debuted her solution to the pollution this week at the Regeneron International Science and Engineering Fair (ISEF). It’s being held in Atlanta, Ga.

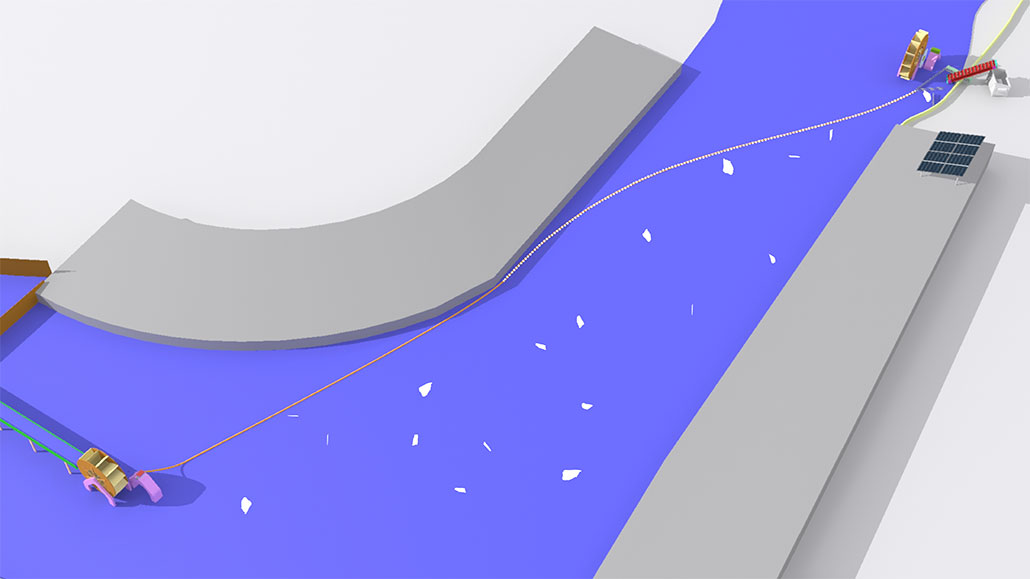

Dakota’s idea was inspired by the Dutch Great Bubble Barrier in Amsterdam.

Like the Dutch system, her backyard pilot-scale system would send a curtain of bubbles up from the river bottom to corral trash and move it to the side of the creek. But this 15-year-old at W.P. Davidson High School challenged herself to make that concept completely green. Hers would run entirely on hydropower and solar energy.

In Dakota’s design, a curtain of bubbles would span the river in a diagonal line. Floating trash would be stopped by the curtain and pushed toward the shore. There, a conveyor belt run by a solar-powered battery would collect the debris and transport it to a dumpster. (She included a waterwheel as a backup power source, because in Mobile, she explains, “you can never tell with the weather.” If it’s not sunny, it’s raining.)

Fish can swim right through the bubbles. In fact, as in a fish tank, oxygen released by the bubbles would help keep the water well aerated.

Building the bubbles

Dakota’s system relies on an air compressor. It sends air through a plastic pipe into which she’s drilled rows of tiny holes. Air escaping through those holes then bubbles to the surface, creating what looks like a curtain. In the future, the teen plans on harnessing the power of the creek to run the air compressor. It would get its energy from water wheels connected by a pulley system. Constructing that component will be part of the next phase of her project.

For now, Dakota has focused on fine-tuning the bubble curtain. That was the most important part to figure out, she emphasizes. “For the bubble system to actually work and actually collect the trash,” she explains, “I have to know how much pressure the air compressor is supposed to push out.”

She got to work in her dad’s tool-laden garage. (It’s where she had helped him build the family’s dining room table, at one point.) After drilling a couple hundred 1.5-millimeter (0.06-inch) holes into a plastic pipe, she attached that pipe to another and tested the combo in her backyard pool.

She had measured the creek’s flow after a big rainstorm to make sure the bubbles would still rise in heavy currents, like after floods when lots of trash would be swept downstream. The rushing water moved at about 1.3 meters (4.3 feet) per second. To mimic that current in a test environment — her backyard pool — Dakota rented a water pump from a hardware store. It was expensive, she says, so she only rented it for one day. That meant she had to work quickly to troubleshoot any problems as they arose.

With the air compressor turned on, she experimented with the pressure, gradually upping it until enough bubbles rose from the pipe to form a full curtain.

Testing with trash

Now it was time to test the curtain’s ability to collect trash, such as plastic soft-drink bottles. Dakota placed bottles that were empty, full of water or weighted with rocks into the water. All of them stopped at the curtain and then slowly bobbed along the curtain until they reached the edge and could go around.

“It was exciting,” says Dakota. “I was like, ‘Yo, this actually works!’”

She was always confident that it could work. She just didn’t expect it to work so well. For instance, she noticed that the bubbles created a current in the pool that pulled tree leaves upwards. This indicates that the bubbles could even help redirect trash up from a creek’s floor.

Dakota was among more than 1,100 high school finalists from around the world who convened in Atlanta, Ga., for this year’s ISEF. Another 500 students competed virtually. Regeneron ISEF, which will dole out nearly $8 million in prizes this year, has been run by Society for Science (the publisher of this magazine) since the annual competition started in 1950.