Bullying hurts — but peer support really helps

Bullying can leave lasting scars, but some schools now use peer pressure to reduce social conflicts

Bullying — or “drama” or “intimidation”— can make kids more susceptible to mental illness as adults. But some schools are reducing conflicts by putting peer pressure to good use.

omgimages/istockphoto

As a child, Belinda (not her real name) got teased for being short and “more sporty” than other girls. She now realizes the kids who taunted her “were kind of jealous of me.” Bullying might have been “a defense mechanism,” she says. Since then, she’s seen other kids getting bullied — and it hasn’t always been easy to do the right thing. Sometimes she’s stuck up for the victim. Other times she’s gone along with the crowd. Now a 10th grader at Ridgefield Park Junior-Senior High School in New Jersey, she thinks she “should have stuck up for more people instead of laughing or watching an incident occur.”

It’s normal for teens to worry about fitting in. Sometimes, though, the desire for acceptance leads to conflict and hurt. Teens might “get into a fight or use jokes or put-downs that they know their peers recognize and approve of,” says Elizabeth Paluck. She’s a psychologist at Princeton University in New Jersey. (Psychologists are scientists who study the mind.)

Whether fist punches fly or jeers ring out, bullying can leave deep scars. New studies show that kids who were bullied suffer more mental health problems, such as anxiety, as adults.

But peers also can exert a powerful influence for good, other studies find. Some schools, for example, have reduced bullying with a program that turns influential kids into positive change-makers.

Bullying takes big toll on victims — and attackers

Even well-meaning teens sometimes poke fun at another student or ignore an insult. They may get angry with a friend. Such anger might even prompt a fight. But these behaviors don’t necessarily count as bullying.

“Part of growing up is being able to negotiate difficult social situations. All kids need to know how to do that,” says William Copeland. He’s a psychologist who studies children’s mental-health disorders at Duke University School of Medicine in Durham, N.C.

Big problems can arise when the jabs and taunts reflect a power struggle. Bullying constitutes picking on a weaker person over and over again, trying to hurt them. Teens may use different labels, such as “intimidation.” Or they might dismiss the behavior as “drama,” says Paluck. But kids who routinely endure such troubles tend to face bigger problems decades later. That’s the conclusion of several studies done in the United States, the United Kingdom and Europe. As longitudinal studies, they monitored impacts in the same people over many years.

In one, Copeland and his coworkers followed 1,420 young people in North Carolina for about 15 years. The researchers interviewed each participant, along with a parent or caregiver. They did this for each child four to six times while the student was between the ages of 9 and 16. Each time, the researchers asked if the child had experienced bullying at school — or had bullied others. They also asked kids if they had gotten depressed or anxious and how often.

Then, as young adults, these people were surveyed several more times. As part of these later surveys, the researchers also examined the participants for symptoms of common mental health disorders.

The results were clear: Childhood bullying took a toll.

Its victims were more likely to suffer from anxiety and panic disorders as adults than were those who hadn’t been tormented as kids. Bullied kids who also bullied others were even more likely to suffer these problems. Especially disturbing, young men who had been both victims of bullying and bullies themselves were at elevated risk for thinking about committing suicide. Copeland and his group published their results in April 2013.

It’s not clear why being both a victim and a bully might pose a special risk for later mental-health problems, Copeland says. He notes that these adults tend to be more impulsive and aggressive than are people who had suffered no bullying themselves. In addition, victims of bullying often have poorer social skills. Those traits may mean that when they tried to gain control by bullying, they failed. And that may have further isolated them socially, he says.

Andre Sourander is a psychiatrist (a doctor who focuses on mental health problems) at the University of Turku in Finland. In 1989, he and some colleagues started following 5,034 people born 8 years earlier. They collected information on any mental-health symptoms. They also asked the kids whether they bullied others and how often other children had bullied them. Parents and teachers answered similar questions for each child. Later, the researchers looked at how these children fared between ages 16 and 29. They also reviewed medical records to see if any had seen mental-health specialists or been diagnosed with a psychiatric illness, such as depression or anxiety.

Compared with participants who were rarely tormented, victims of bullying were more than twice as likely to develop a psychiatric illness later in life. As in Copeland’s research, those who had been victims and bullies were at highest risk of mental health problems in adulthood. (What about the children who bullied others but were not bullied themselves? Only those who showed psychiatric symptoms at age 8 were likely to also do so when they were older.)

Sourander’s team reported its findings in the February 2016 JAMA Psychiatry.

The U.S. and Finnish studies used different methods. Still, they came to the same conclusion. That suggests researchers can be more confident in the findings, says Copeland. Those data show “how damaging bullying can be on children long-term,” he says. He hopes these results “encourage kids to stick up [for others] when they see friends being picked on.”

As damaging as abuse and neglect

Copeland has also compared the effects of bullying to the impacts of childhood abuse and neglect. In that study, he teamed up with psychologist Dieter Wolke at the University of Warwick in England.

The two studied 18-year-olds in the United States and United Kingdom. They asked these 5,446 young adults to describe childhood experiences of bullying, of physical abuse and any neglect. Then they identified any signs of mental health problems. These included anxiety, depression or attempts to cope with problems by injuring themselves. (This behavior is called self-harm.)

The results surprised the researchers. “The effects of bullying were stronger than being physically abused or neglected,” Wolke says. Indeed, he argues, bullying “throws a long shadow over people’s lives.”

That shadow can be physical as well as mental, adds Louise Arseneault. She’s a psychologist at King’s College in London.

In a recent study, she asked 45-year-olds if they had been bullied as kids. She also assessed the participants current health. Compared to people who were rarely bullied in childhood, those who had been victims of frequent bullying were more likely to be depressed or have suicidal thoughts. But that’s not all. These bullying victims also were more likely as adults to be obese — extremely overweight. And they had higher levels of a blood marker known as C-reactive protein (CRP). Studies have linked elevated CRP levels to an increased risk of heart disease.

Taken together, Copeland concludes, childhood-bullying exerted a lasting health toll into at least middle age.

Story continues below image

Bullying can be prevented

Public opinions about bullying tend to fall into extremes, Arseneault says. Some people blame bullying for a range of problems. Others think the concerns are overblown. Overall, she believes, more people recognize bullying as “a serious problem for young children.” Unfortunately, she adds, this concern “does not always translate into real action. And this may be part of the problem.”

In 2011, President Barack Obama and First Lady Michelle Obama organized a White House conference on bullying prevention. News accounts reported that the President said a key goal had been to “dispel the myth that bullying is … an inevitable part of growing up.” The event took place several months after several well-reported teen suicides. Many people believed these adolescents took their lives as a result of bullying at school and online.

One student killed himself by jumping off the George Washington Bridge. He had been an 18-year-old at Rutgers University in New Brunswick, N.J. The tragedy prompted state legislators to pass a law requiring anti-bullying programs at New Jersey public schools. Most U.S. states now have laws and policies that define bullying as unacceptable. (You can find out more about them here.) But there is no federal law telling schools how they should prevent the problem. And it’s hard to even tell if school programs are working.

Many anti-bullying programs, such as school assemblies and discussion groups, are run by teachers and other school staff. That’s not the most effective approach, says Paluck at Princeton. If people hope to change student behaviors, she says, “the message can’t come from adults.”

She and her Princeton coworkers came up with a new approach to cut school conflicts, including bullying. Students would lead these efforts. The key was identifying what Paluck calls social influencers. These are the 10 percent of students who get the most attention from their peers.

These are not necessarily the most popular kids in a school. But smaller peer groups tend to look to them “to figure out what behaviors are desirable and normal,” Paluck says. If social influencers took a public stand against bullying, maybe that would make such incidents uncool.

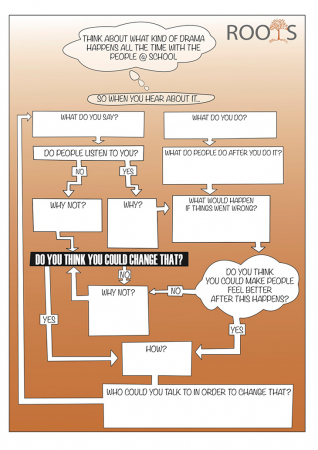

The researchers call their program Roots. It uses influential kids as “the roots of the movement,” Paluck explains. (When her team asked students about possible program names, Roots “was the one they were least able to make fun of.”)

The researchers invited public middle schools in New Jersey to test the approach. Each used questionnaires to identify social influencers. These included people like Belinda, who emerged from her childhood bullying experiences more aware of how hurtful such behaviors can be.

In surveys, students identified who they interacted with at school and on social media. These influencers, and some other students, received invitations to the Roots group at their school. The groups met every other week. School counselors encouraged students to talk about uncomfortable situations — for example, times when teens tell racial jokes or make fun of people for how they dress.

The Roots groups also brainstormed how to make positive changes. At Ridgefield Park Junior-Senior High School, teens came up with a fun idea. They organized a “mix it up” lunch period. Here, students were encouraged to talk to new people. Instead of eating with the same crowd, “you’d mix it up and change who you sit with,” explains Sunni Roberts. She’s a counselor at the school.

The event included activities and games. At one station, students thought of stereotypes — for example, “boys are better at math” or “girls cannot play all sports.” These ideas can provoke taunting or other conflicts. Students wrote the stereotypes on pieces of paper. They folded each paper into an airplane and flew them through a hoop. This was meant to symbolize how kids could get rid of such destructive mindsets, explains Roberts.

Across New Jersey, 56 schools took part in Roots groups as part of the Princeton experiment. School administrators tallied disciplinary events caused by peer conflicts. After one year, the number of incidents had dropped by 30 percent in schools with Roots programs — from 2,695 to 2,012. The benefits were highest in Roots groups with more social influencers. The researchers posted their findings last year in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. They also have posted the Roots curriculum online for other schools to use.

“Roots has made a difference in many ways,” says Belinda. “It has helped students open up and let others know when they’re being bullied.” Hopefully, equipping kids to stand against bullying also will lead to healthier lives in years to come.

Suicide is the second leading cause of death among young adults ages 15 to 29 as of 2016. If you or someone you know is suffering from suicidal thoughts, please seek help. In the United States, you can reach the Suicide Crisis Lifeline by calling or texting 988. Please do not suffer in silence.