An ancient log shows how burying wood can fight climate change

A blanket of clay soil helped it hold onto its carbon for about 3,775 years

Scientists unearthed this 3,775-year-old piece of wood in Canada. It had held onto at least 95 percent of its carbon, thanks in part to being covered by a layer of clay soil, a new analysis shows.

Ning Zeng

In 2013, Ning Zeng came across a very old, very important log.

At the time, he and his colleagues were digging a trench in the Canadian province of Quebec. They planned to fill it with 35 metric tons (39 U.S. tons) of wood. Then, they would cover that wood with clay soil and let it sit for nine years. The goal? To show that the wood wouldn’t decompose.

If it worked, this exercise would prove that that burying plant matter could be a cheap way to store carbon. Keeping such carbon from entering the atmosphere could help fight climate change.

But while digging their trench, Zeng’s team unearthed a pristine, twisted log. It was very old — older than anything they could have possibly produced in their experiment.

“I remember standing there just staring at it,” says Zeng. He’s a climate scientist at the University of Maryland in College Park. He recalls thinking, “Wow, do we really need to continue our experiment? The evidence is already here — and better than we could do.”

The uncovered log was once part of an Eastern red cedar. Some 3,775 years ago, this tree had drawn carbon dioxide, or CO2, from the air and then used its carbon molecules for the creation of wood. When it died, the tree got buried beneath as little as two meters (6.5 feet) of clay soil.

That barrier, it now turns out, allowed the log to hold onto at least 95 percent of its carbon. Zeng and his colleagues shared their findings September 24 in Science.

“Scientists and entrepreneurs have long contemplated burying wood as a climate solution. This new work shows that it is possible,” says Daniel Sanchez. An environmental scientist at the University of California, Berkeley, he did not take part in the study.

“High-durability, low-cost climate solutions like these hold immense promise for fighting climate change,” he says.

Burying: a practical proposal

New solutions for climate change are sorely needed. Cutting greenhouse gas emissions isn’t enough to reach atmospheric CO2 levels to slow global warming. And some 10 billion more tons of carbon need to be pulled from the atmosphere and stored each year by 2060.

Just by growing, plants store the carbon from about 220 billion tons of CO2 each year. But much of that carbon will get released back to the air when the plants die and break down. Stopping just a fraction of that breakdown, by burying wood, could help. But this strategy relies on finding conditions that would stop air, water and microbes from breaking down buried carbon for a long time.

The newfound ancient log gives researchers a clue.

Zeng now suspects the clay blanket helped keep oxygen from reaching the log, even though it wasn’t buried very deep. “This kind of soil is relatively widespread. You just have to dig a hole a few meters down, bury wood, and it can be preserved,” he says.

Burying wood could cost as little as $30 to $100 per ton of CO2, the researchers estimate. That simplicity and low cost makes wood vaults more practical than other carbon-catching techniques, Zeng adds. For instance, tech designed to pull carbon directly from the air costs $100 to $300 per ton of CO2.

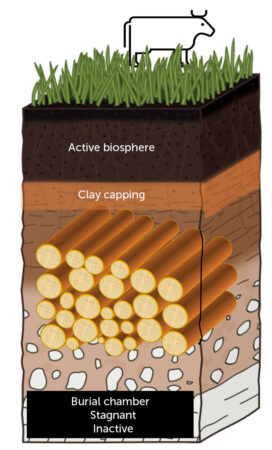

Underground wood vaults

This diagram shows the structure of a proposed wood vault. In this setup, buried wood rests below a layer of clay soil. That soil then keeps oxygen from reaching the wood, helping it to retain its stored carbon.

It’s not yet clear if scientists can recreate the conditions that preserved the Canadian log. But if so, this method could store up to 10 billion tons of carbon each year.

Despite finding the ancient log, Zeng’s team carried out its planned experiment. They’re wrapping up the analysis now. What they learn should help point to best practices for storing carbon in buried wood.

But the log itself shows the promise of wood vaults, Zeng says. “We now have the evidence to say ‘yes, it’s ready to be implemented.’”