California’s Carr Fire spawned a true fire tornado

Not a common fire-whirl, these are amazingly rare freaks of nature

Dramatic image of a fire truck going in to fight the Carr Fire outside Redding, Calif., in late July. On July 23, the intense heat and debris from this fire created a fire tornado.

E.L. Karey

What’s scarier than a tornado? How about a tornado made of fire? On July 26, 2018, the so-called Carr Fire outside Redding, Calif., spawned the strongest tornado in state history: a fire tornado, or firenado.

This rare and terrifying phenomenon was only the second true fire tornado in recorded history — and the first witnessed in the United States.

Wildfires have become an all too common phenomenon in California. The region’s low humidity and scarce rainfall make it an environment ripe for blazes. In fact, much of the state should burn naturally every 50 to 100 years or so. An occasional fire can even help the ecosystem. It’s a way for nature to restore nutrients to the soil while cleansing the landscape of an overgrowth of moisture-robbing vegetation. But people have been building homes in these regions. So when a forest goes up in flames, so too can houses. (Witness the estimated 6,000-plus homes destroyed by the so-called Camp Fire, this month, in Paradise, Calif.)

The Carr Fire was first reported on July 23, west of Redding, Calif. An RV trailer suffered a flat tire, which caused the wheel’s metal rim to scrape against the roadway. Authorities believe that sent sparks flying, USA Today reported in August.

Dry debris nearby caught fire. Eventually, this blaze consumed an area three times the size of Washington, D.C., according to CalFire. That’s the state’s wildfire-fighting agency. The flames spread from forest to neighborhoods. And by the time it finally died out, the fire had claimed 7 lives and 1,604 homes and other structures.

But the truly remarkable part: This inferno grew so strong that it unleashed a massive tornado.

Wildfires can make for wild weather

Roughly half of all land burned in U.S. wildfires in 2017 was in California, Montana, Nevada, Texas and Alaska. That’s according to a November 2018 report by the Insurance Information Institute. And because of California’s large and dense population, wildfires in this state are among the most costly, both in terms of damage and lives lost.

Much of California is dry almost year-round. Large parts of it also get quite hot. Winter is usually the wettest season. That’s when big Pacific storms carry the Pineapple Express — a river of moisture that develops in the middle atmosphere. These storms target the California coast with a seeming firehose of moisture. Those rains fuel the growth of vegetation.

In the spring and summer, winds from the west pull in cool air from the Pacific Ocean. That gives San Francisco its famous fog. These winds also force moist air up the mountains. But when it sinks back down on the other side of the state’s mountains, that air dries out. This desert-like air can suck the moisture out of anything it touches. So any dead plant matter begins to dry up. By mid-summer, much of the ground throughout the state is littered with brittle sticks and leaves. This becomes a powder keg of fuel for a fire to gobble up. Lightning, unattended campfires, discarded cigarettes and sparks from vehicle tailpipes — all of those can ignite the dry forest debris.

Farther inland, winds swirl clockwise around a semi-permanent system of high pressure that parks itself near Reno, Nevada. This sends occasional spurts of wind and dry air westward through the Santa Ana Mountains and Sierra Nevada. These so-called Santa Ana winds can top 97 kilometers (60 miles) per hour. They dry the air out and can fan the flames of a wildfire.

If they get big enough, wildfires can create their own weather. The largest of them suck in so much air that the entering winds can flow at speeds of up to 130 kilometers (80 miles) per hour. These winds also supply fires with plenty of oxygen, which the blazes need to burn.

Once in a while, a wildfire will reach so high into the atmosphere that it causes rain. That happens when the warm, steamy updraft carries water vapor to a level where this gas condenses and falls out as liquid droplets.

Some wildfires even produce lightning. Soot, smoke, ash and tree-formed hydrocarbons can become electrically charged as they interact with ice crystals above 7,600 meters (some 25,000 feet). The ice takes on a positive charge. Raindrops become negatively charged. This charge-producing phenomenon has a really long name: triboelectrification (TRY-boh-ee-LEK-trih-fih-KAY-shun). When the electrical charges between the ice and rain grow large enough, a lightning bolt can pass between them.

The Carr Fire churned up some particularly wild weather — a true fire tornado. And one key factor behind that was the speed of the storm’s updraft.

The evolution of a fiery ‘tornado’

The National Weather Service, or NWS, releases weather balloons to collect a vertical profile of the temperatures, humidity, wind speeds and barometric pressure as they rise through the atmosphere. One of these daily soundings was taken with a balloon sent up before sunrise from Oakland, Calif., on July 26.

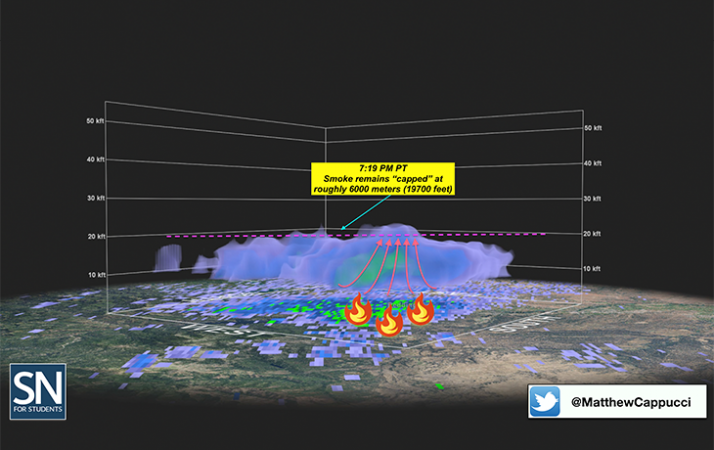

The balloon’s instruments detected a thin layer of warm air at about 1,000 meters (3,280 feet). Known as an inversion layer, it tends to hold air near to the ground from rising high into the atmosphere. In the Carr Fire, this “cap” trapped hot smoke close to the ground.

As energy continued to build beneath the inversion, the hot air pushed upward. That caused the cap to rise… and rise… and rise some more. This occurred all morning and afternoon. Around dinnertime, those hot gases had lifted the inversion layer to right around 6,100 meters (20,000 feet).

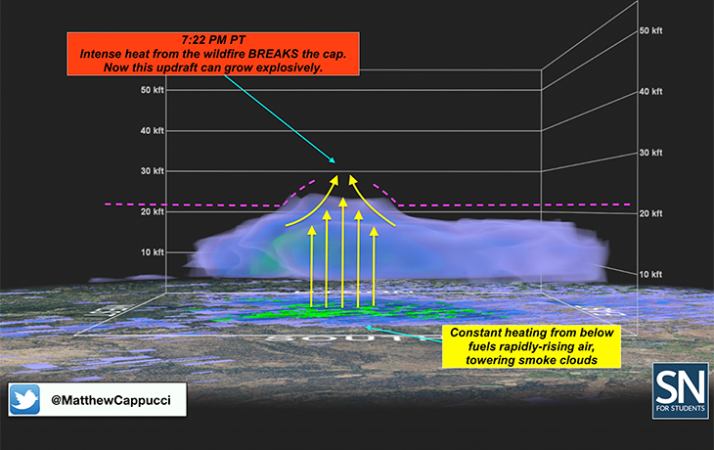

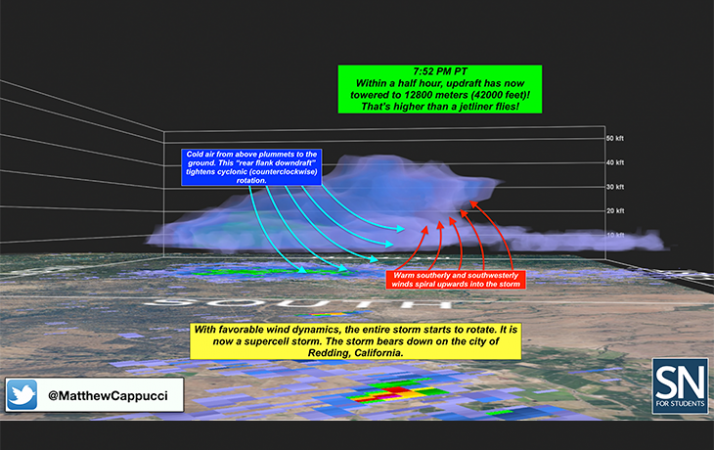

Then, around 7:20 p.m., the fire won. Two upwardly rising plumes of hot smoke and gas punctured through the cap. Within a half hour, these updrafts soared explosively — doubling in height to 12,800 meters (42,000 feet). That’s above the altitude at which jet airliners fly.

When the updrafts busted through the cap, they spanned multiple layers of the atmosphere. Wind shear shoved the budding storm clouds in many different directions. There also was plenty of rotational energy in the atmosphere — what’s known as vorticity. In short order, he towering updrafts started to spin.

As the fires grew in height, the rotation of winds within them became more intense. As this rotating column of air was vertically stretched the conservation of angular momentum came into play. Think of an ice skater twirling. As she draws in her arms, she spins faster. The same thing happened here. The rapid doubling in height of the updrafts stretched the columns of spinning air. As their radius shrunk, they rotated faster. Before long, the fire clouds were spinning like a top.

It was the southern storm “cell” — one individual updraft — that produced the fiery tornado. At times this cell approached 0.8 kilometer (a half mile) wide. It became the first documented firenado in U.S. history.

A fire tornado is a true tornado. It’s born from rotating clouds and then reaches down from the clouds. Its winds are incredibly powerful, and it can have an impressive, potentially deadly impact. Plus, a firenado is incredibly rare.

News accounts might give you a different impression, though. They sometimes use the term firenado to describe something very different — a firewhirl. These are much, much smaller than a firenado.

Such small whirling masses of air usually are no more than a meter or two (up to 8 feet) across. Wildfires can spew these whirls of twirling, fiery debris by the dozen. One may even form over backyard campfires. They tend to have the same strength as leaf swirls on a gusty, fall day, and last less than a minute. More importantly, they’re not connected to a cloud. They just spin up from the ground in response to intense heat at the surface.

How strong was the Redding firenado?

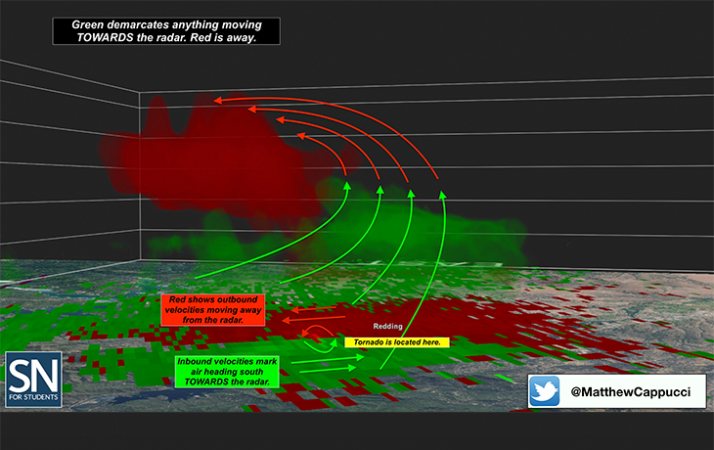

After receiving reports of significant damage in the wake of the Redding fire’s tornado, the NWS Sacramento office sent out a team of meteorologists to investigate. One NWS tweet on August 2 noted that: “Preliminary reports include the collapse of high tension power lines, uprooted trees, and the complete removal of tree bark.” Its experts also had found evidence of winds in excess of 230 kilometers (143 miles) per hour.

The event met the American Meteorological Society’s definition of a tornado. AMS characterizes a tornado as a “rotating column of air, in contact with the surface, pendant from a cumuliform cloud.” The word cumuliform means a cloud with a powerful updraft. The July fire tornado was rooted in the massive cloud — one that were rotating. It also was fed by an intense updraft. And it was attached to a rapidly-growing fire-generated “cumuliform” cloud. It was, in fact, a cumulonimbus cloud.

Scientists use the Enhanced Fujita Scale to rank the strength — wind speed and destructive force — of tornadoes on a 0 to 5 scale. The Carr Fire’s tornado was a powerful EF-3. Most of the thousand or so U.S. tornadoes that touch down each year are EF-0’s or EF-1’s. Fewer than 6 in every 100 reach an EF-3 or higher.

California had seen two EF-3’s in the 1970s. But neither was more than 60 meters (200 feet) wide. The Carr Fire tornado was 12 times that broad. Indeed, the Redding firenado was the strongest tornado of any type ever recorded in California.

The first recorded fire tornado was Down Under

On January 18, 2003, lightning sparked a wildfire near Canberra, Australia. Its smoke produced a cumulonimbus cloud. And like the system in Redding, the clouds grew into a supercell thunderstorm.

The Australian wildfire produced winds of up to 130 kilometers (80 miles) per hour. This challenged efforts to curb its growth. Jason Sharples is a fire scientist at the University of New South Wales in Sydney, Australia. He and three other scientists described this fire’s tornado in a 2013 paper. At some point, they note, clouds associated with the violent fire began to rotate. This spawned a terrifying twister. It was even worse than California’s. Though it stayed mainly over open countryside, it did level one neighborhood.

Jim Venn, a resident of the suburb of Wanniassa, captured the twister in a photograph from his back deck. The scientists then used math to analyze the photo to estimate the size of the cyclone’s rotating structure. They gauged the updraft speed of the tornado at an enormous 200 to 250 kilometers (124 to 155 miles) per hour. That’s enough to lift and toss a vehicle. It may come as no surprise, then, that this funnel was able to throw the 7-metric-ton (15,000 pound) roof of a water tower more than 0.8 kilometer (a half mile).

The tornado, which touched down six times, was also captured on video. The scientists argue it “meets the definition of a tornado.” It also appears to stand alone, with the Redding event, as the only two true tornadoes born of fire.

And now come reports that another firenado may have sprung to life on November 9. It was at the edge of the deadly Woolsey Fire in Malibu, Calif. Something tore up trees and pulled the posts for power lines out of the ground. And video showed a clockwise-spinning vortex.

That rotation, however, is opposite to the spin direction of most tornadoes in the northern hemisphere. A later analysis of Doppler radar now suggests this furious funnel may have been a landspout — a twister-like vortex with a tornado’s strength. This blazing cyclone appeared to contain winds of 129 to 153 kilometers (80 to 95 miles) per hour. It likely formed in response to small eddies (circling winds) moving downhill and gathering strength. Unlike most full-fledged tornadoes, this twister’s circulation was shallow. It gathered and lofted enough loose debris to be picked up on radar. Though scary, it wouldn’t have been a firenado.