Cannabis may alter a teen’s developing brain

Adolescent marijuana use may affect areas that help rein in impulsive behavior

Smoking pot as a teenager may have lasting effects. A brain area involved in decision-making developed differently in teens who used cannabis than in peers who stayed away from the drug.

Mayara Klingner / EyeEm/ Getty Images Plus

Smoking pot as a teen likely affects the still-developing brain, a new study finds. The region most at risk helps guide decision-making.

Matthew Albaugh is a psychologist at the University of Vermont in Burlington. He was part of a team that scanned teens’ brains with an MRI machine before and after they started to use marijuana (also called cannabis or pot). The study included 799 teens in Germany, France, Ireland and England.

Participants had their first scan at age 14. None reported using marijuana at this point. Five years later, the teens returned for a second scan. Now 369 of the adolescents (46 percent) reported they had tried cannabis. About three-quarters of these said they had done so at least 10 times.

One part of the brain changed more in cannabis users than non-users. Called the prefrontal cortex, it sits right behind the forehead and above the eyes. This region is involved in decision-making and other tasks. It tends to thin during adolescence to help the brain work more efficiently. But that thinning sped up in teens who reported cannabis use. The more drug the teens used, the faster the prefrontal cortex thinned, Albaugh’s team now reports.

That may sound like a good thing, like the brain is maturing more quickly on pot. But researchers don’t view it that way. Notes Albaugh, exposing young animals to pot causes their brain to thin too early. That can lead to long-lasting problems with behavior and memory.

The teen study does not prove that cannabis caused the faster thinning. But it adds to growing evidence that early cannabis use may affect brain development.

Albaugh’s group described its findings June 16 in JAMA Psychiatry.

Brain ‘pruning’ and cannabis

Jacqueline-Marie Ferland is a brain researcher at the Icahn School of Medicine in New York City. The prefrontal cortex is “the adult in the room,” she says. One of its jobs is to combine different pieces of information as we make decisions. A mature prefrontal cortex, she says, controls behavior by toning down emotions. It also tamps down impulsive actions.

Teens often take more risks than children and adults. The reason? Different parts of the teen brain mature at different rates. Greater risk-taking often promises greater rewards. The prefrontal cortex that guides rational behavior matures more slowly than do parts of the brain that control our emotional response to rewards. In fact, the prefrontal cortex is the last brain region to fully mature. It’s not complete until around age 25. Thinning is an important part of that process.

Janna Cousijn is a psychologist at Erasmus University in Rotterdam, the Netherlands. She compares a young child’s brain to a very thick forest. “As we grow up, we often decide to take similar paths within that forest,” she says. That means some frequently traveled paths — connections among brain cells — start to emerge.

Favored paths become better established as we age. This lets brain signals pass down them faster. Rarely or never-used paths disappear. Thinning of the prefrontal cortex is part of this “pruning.”

The active chemical in cannabis is called THC. It speeds up thinning of a rat’s version of the prefrontal cortex. THC binds to docking stations in brain cells. Those docking stations are called CB1 receptors. That CB is short for cannabinoid (Kah-NAA-bin-oid), meaning these receptors are ideally structured to respond to cannabis compounds known as cannabinoids. These include THC.

Rats given THC during adolescence lose some brain connections that would otherwise stick around into adulthood. This can alter the rodents’ behavior and memory. How much depends on the amount of THC and the animal’s age.

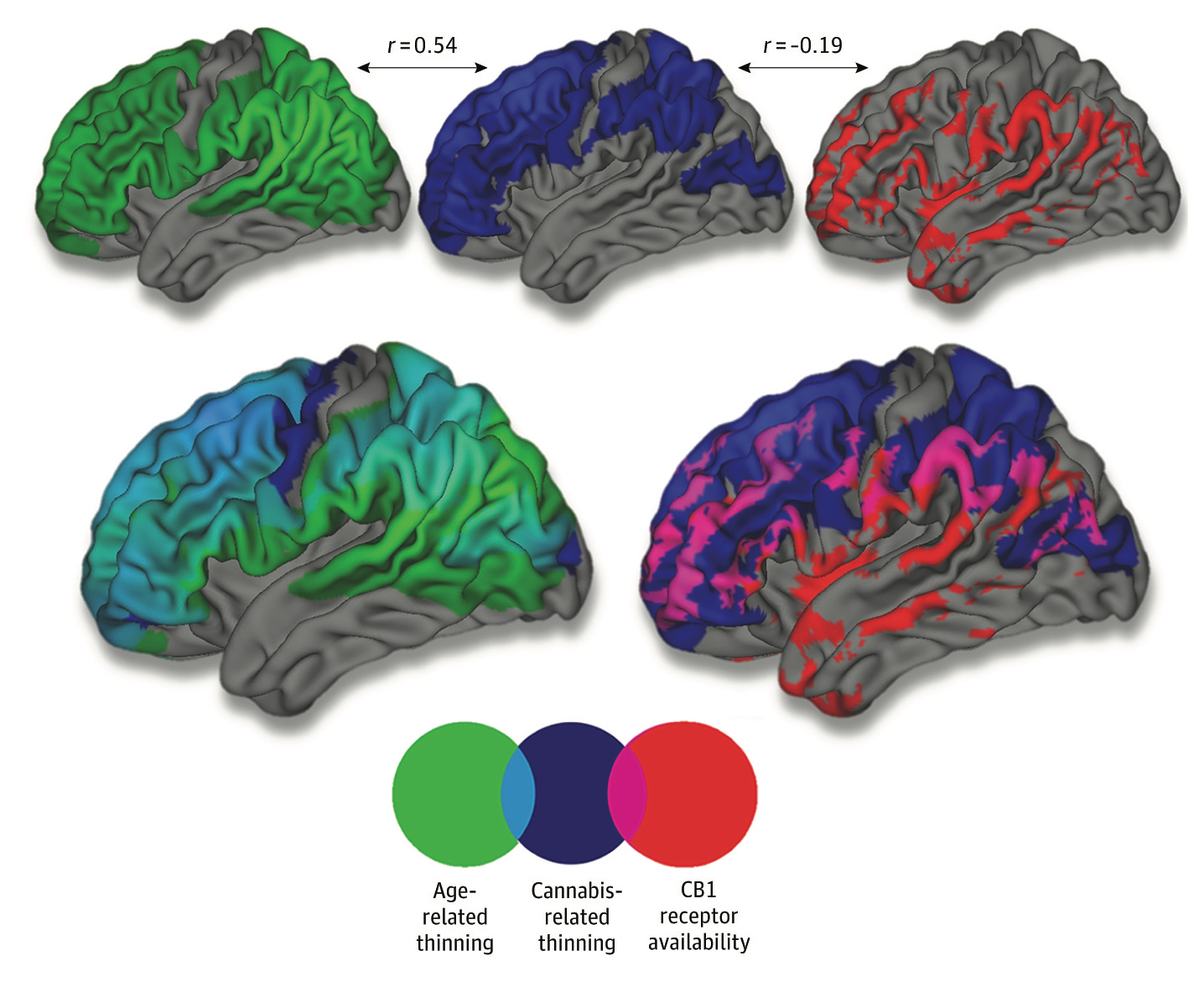

Researchers cannot study a direct link between THC and prefrontal-cortex thinning in people. But Albaugh’s colleagues found more CB1 receptors, on average, in the prefrontal cortex of 21 adult men than in other brain regions. (The imaging method uses a radioactive material, so this could not ethically be confirmed in teens.)

It is notable that the CB1-rich part in adult brains overlaps with the area that thins faster in cannabis-using teens. The overlap does not prove that cannabis causes the change. It does, however, add to evidence that it may.

A window of vulnerability

Cannabis has medical benefits for some people. Adults can legally use it in some U.S. states and countries. But that, says Albaugh, does not mean cannabis is harmless for young users. “Brain areas that change the most during adolescence may be especially vulnerable to cannabis exposure,” he says.

To learn if the thinning persists into adulthood, he is now analyzing the same people’s brain scans at age 23. He will also test if the brain changes his group has recorded relate to unwanted adult outcomes. This may include lower graduation rates, delayed graduation or more mental health disorders.

“It is critical to know if teen cannabis use may change how you function as an adult,” says Ferland. Until more is known, many researchers recommend postponing any cannabis use until adulthood. They also suggest limiting its frequency and using only low-potency products.

One last thing to note: Alcohol is the most common drug of adolescence in many countries. And researchers have found that alcohol and cigarettes often do more damage to the brain than cannabis. (The amount used matters greatly for all three.) But even smaller brain changes from regular use can lead to addiction. “And developing any addiction is damaging to yourself and others,” says Cousijn. Adds Ferland, “starting to use drugs as a teen greatly increases the risk of addiction later in life.”